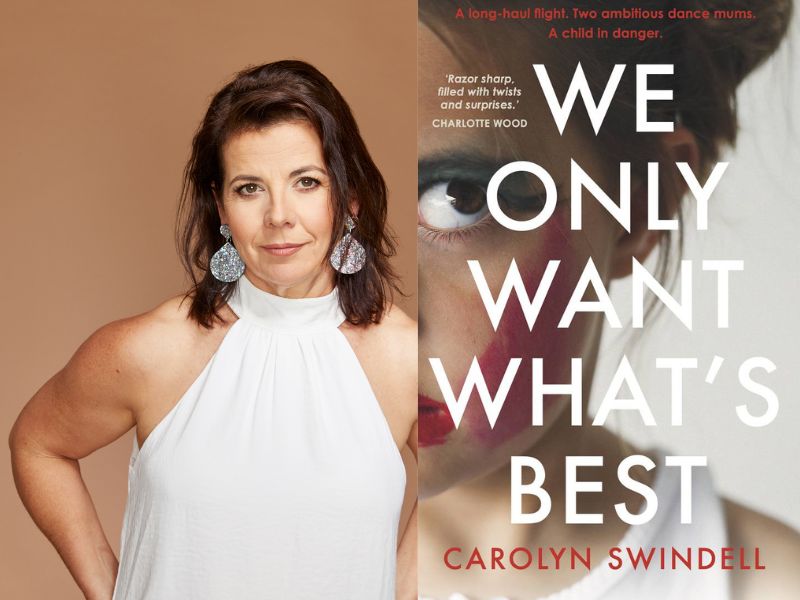

We Only Want What’s Best is Carolyn Swindell’s pacey, sharp-witted debut novel, set on a long-haul flight to Los Angeles. Two dance mums are accompanying their daughters as part of the Expressions dance troupe headed for Disneyland. All events take place between ‘17 hours and 32 minutes to destination’ and ‘International Terminal LAX’. Each chapter title is time stamped and exists along the continuum of a countdown that hurls us closer towards the destination.

At the core of the book is an emerging scandal that makes for eager reading. You’ll readily find yourself locked in to the game, awaiting revelations. This is rendered even more memorable by, not just the swathe of distinct and endearing characters, but how heavily the scandal hits.

My very immersion in the story made me feel implicated, which also feels like the point. Indeed, reading the novel in public, displaying Affirm Press’ aptly chosen, suggestive cover of a child’s headshot, close up with smudged eyeshadow and lipstick, had me hyperaware of how others perceived me holding it. And so, in my dual state of self-conscious investment, I felt a deep solidarity with those mothers finding themselves right on the knife edge of issues involving their daughters.

The story is told from three alternating perspectives. Simone is elegant – an ex-ballerina, comfortable in the art world. Now married to a wealthy businessman and philanthropist, she’s also comfortable in business class. She loves her daughter Zahra – precocious and star of Expressions – but she’s not under any false illusions about Zahra’s talent, viewing Expressions as just a local dance school. She is proud and private. She doesn’t share the fact of her multiple sclerosis with people outside her family, and she lets fellow dance mum Bridget believe that she needs support walking to the departure gates because of a sprained ankle.

Bridget has moved interstate to get her daughter Becky – kind, earnest and younger than Zahra – into Expressions. She’s a young mum, in her late 20s, and the fact she has spent much of Becky’s life as a single parent has given her a fierceness that’s loveable to witness. She’s open and chatty; it amps up when she’s nervous. When the drama hits, her extroversion gives way to unalloyed emotion and she goes into fight mode for Becky. She doesn’t have all the facts, and the alcohol and sleeping tablets she’s consumed don’t mix well; her reflex is to protect and confront.

Her messy, full-throttle approach to challenging problems is beautiful, it endears Bridget to us; but it makes for uncomfortable viewing. We inhabit a calmer and more informed perspective than Bridget, and so she’s cast in a light reflective of Simone’s opinion of her – as weird, overtaken with emotion and as a problem that needs handling. At the same time, our judgement of Bridget is also a gateway to us judging Simone. ‘Not so fast,’ we want to say, because we’ve also been on this journey with Bridget and appreciate where she is coming from.

The story proceeds in this manner, tugging us back and forth amid lifelike interpersonal politics, and thus every instance of judgement also inspires reflection and compassion.

The third perspective is from the children: Becky, Zahra and Zahra’s friend Keely. The dynamics between these three are just as fraught and complex as those of the adults. What’s different about this perspective is that it’s in third person. It’s a clever juxtaposing choice that affords the children a kind of privacy. Like parents, like mothers, we may observe them, but we aren’t let into their thoughts and we don’t get to fully inhabit their world. The effect is one of estrangement; we’re always on the outside.

We’re free to feel and interpret, but we are powerless to know the whole situation and, importantly, we are also powerless to intervene. Readers will also invariably fall back on their own experiences of being teenagers as a means to interpret and imagine how they would manage things.

This experience of being on the outside, and of using your past as a guide, both enacts and is a part of the novel’s perspective of motherhood. Bridget and Simone are responsible for their teenagers and, having been their own versions of teenagers in the past, they have a distant sense of exactly what these responsibilities are. Their versions of teenagehood were also highly personal, utterly their own, and so – like us – they’re left to do the best they can from the outside. They definitely “only want what’s best” and yet they can never know quite what best is.

Read: Performance review: Maho Magic Bar, Chinatown

We Only Want What’s Best showcases the futility of trying to get it right, as well as the importance of trying. It will also leave you revelling in examples of maternal ingenuity and wisdom.

We Only Want What’s Best, Carolyn Swindell

Publisher: Affirm Press

ISBN: 9781922848499

Paperback: 320pp

RRP: $34.99

Publication: 28 March 2023