Warning: readers are advised that the following review includes discussion of depression, suicide and bullying.

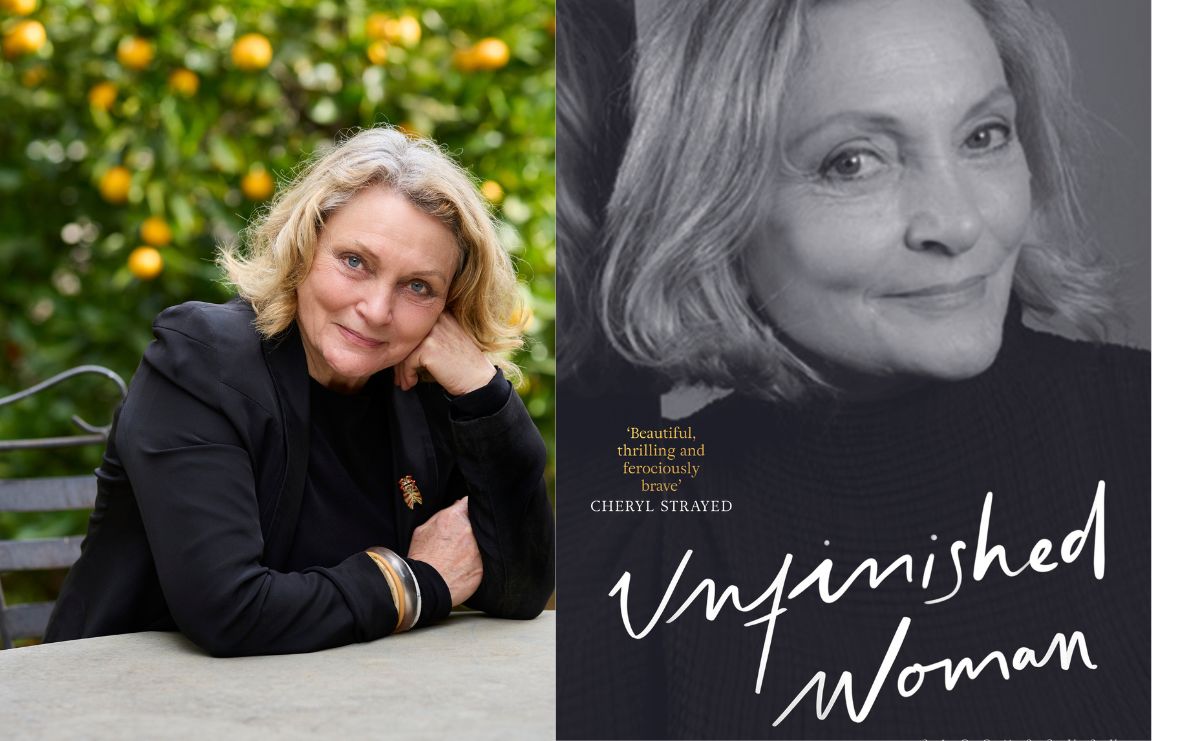

Robyn Davidson is best known for her international best seller Tracks about her trek across 2700 kilometres of Australian desert in 1977. Her new book, Unfinished Woman, tells of another journey, this time into her past. It is mostly, she says, about her mother, who died by suicide in 1961, when the author was 11 years old.

Davidson wanted to write her own story, excavate her memories, in order to release her mother from ‘the prison of other people’s stories’ where she’d been ‘misrepresented, dishonoured, murdered’. Up to now, she says, her sister, Margaret, has owned copyright on the story of her mother and her version is so different that it is as if they had come from different wombs.

Unfinished Woman has been 25 years in the making. Davidson began working on it as she approached the age of 46, the age at which her mother died. Using a fragmented narrative, Davidson moves back and forth through time, and often circling back to her childhood years spent at Malaba, a cattle station in Mooloolah in south-east Queensland.

I am the same age as Davidson and found her descriptions of growing up in the 1950s and 60s to be utterly compelling. The bohemian lifestyle and shared communal households of the late 60s and early 70s were an exciting and enriching time; for many of us, Davidson included, who grew up in dysfunctional families where our parents suffered unhealed trauma, we had a glimpse of what a safe family could be like.

It was at Malaba that her mother began to suffer from severe clinical depression and the family moved down to Clontarf, Brisbane, driven off the land by drought and financial disaster, and also to be closer to doctors. One afternoon, Davidson came home from school and was told her mother had killed herself. In the early 1960s, suicide was considered a sin; it was shameful and cowardly. After her death, it was as if she had never existed. She was never mentioned in the family.

From the day her mother died, until she began writing this book, Davidson says she didn’t think about her mother once.

Davidson squeezes a lifetime into almost 300 pages and much seems unrelated to her mother, who remains a shadowy figure. The person who stood out for this reviewer was her sister, who is six years older. Siblings after all are most people’s longest-lasting relationships and can have just as much or more influence on our lives than our parents.

As children, Davidson worshipped her sister. She also feared her. She was like a giantess. During their fierce fights, Davidson wondered if she would die before her breath came back, though her tears were not from her sister’s punches but her words.

‘She turns and I know what’s coming, because it has come so often before. Her nails dig into my arm, the air goes out of my stomach, and the sneering, loathing refrain pours down: “useless, ugly, stupid”.’

This seems more than just the normal rough and tumble of sibling rivalry and Davidson was relieved when Margaret, at 14, went to boarding school in Brisbane as there would be ‘no more bullying’. Her sister’s contempt leaves a deep mark. Davidson says that her walk across the Australia desert in 1977 when she was 27 gave her a kind of integration and ‘proof that “useless, ugly, stupid” [the words her sister had taunted her with] was not all there was’.

After her desert walk, Davidson spent several decades overseas, mostly in London and India. She provides few details of her tumultuous relationship with Salman Rushdie in her mid-30s, but blames herself for the ongoing abandonments. ‘There had to be something in me, in my behaviour, that caused them.’ She harks back to her childhood, where she was primed, she says, to assume that any anger coming her way was her fault.

‘Just as my birth left its effect in my sister’s development, so her contempt marked my unfurling ego. It is with me still, that malformation ‒ a habit of worthlessness ‒ and it has governed much of my fate. I have accepted as normal that deep love from someone can be mixed with a desire to obliterate.’

Davidson gives more details about her relationship with Narendra Singh Bhati, a Rajput aristocrat and politician with whom she lived, on and off, in the Himalayas for more than 20 years until his death in 2011. Most of the time she felt safe with him, but at other times she was distressed at the growing chasm between them. He drank heavily daily, but Davidson spurns the use of the term alcoholic (‘a Western concept’, she quips). In India, she says, there is more tolerance of drunkenness.

Davidson is very tolerant of bad behaviour, especially her sister’s. They became estranged as adults (the reasons are not given), but met up in 1996 when Davidson returned to Australia to promote her book Desert Places. The reunion was not the happy meeting she hoped for. When she went to hug her sister, it was like ‘approaching the same pole of a magnet ‒ a repelling force that increases the closer you get’. Her voice was cold and bitter and vibrated with ‘loathing ‒ the longing to crush something loathsome’.

Davidson excuses her sister’s anger and says Margaret is acting out of her own loss and grieving and behind her behaviour is pain. But the sister is an adult now and responsible for healing her pain, not acting it out. Compared to the trauma of her mother’s suicide, Davidson’s relationship with her sister seems to be a constant wounding of ongoing trauma.

Disappointingly, we never get to find out her sister’s version of their mother’s story, we never get to hear directly from Margaret at all. There are no quotes from letters or conversations, only the author’s recollections. According to Davidson, memory is ‘shot through and through with falsehood’ and on several occasions she points out that one must ‘never forget the crucial importance of point of view’. Although her recollections of her sister’s bullying ring true, I couldn’t help but wonder about her sister’s point of view. What does she think?

And why is it that Davidson’s sister is seldom if ever mentioned in reviews or interviews with the author? When she is mentioned, it is only in passing as in a recent review in The Sydney Morning Herald where Candida Baker writes that Davidson and her older sister ‘had a somewhat uneasy relationship’. That is an understatement.

Read: Performance review: New Reality, Immigration Museum

Writing can change the brain, heal the pain of trauma, cast off shame. There is now even written exposure therapy! At the end of Unfinished Woman, Davidson seems to have come home to herself. After a rather nomadic lifestyle, she is back in Australia for good. She has settled down in Castlemaine, a former goldmining town in regional Victoria, where she is renovating an old stone house. She insists she will never write again. I hope she never stops.

Unfinished Woman, Robyn Davidson

Publisher: Bloomsbury

ISBN: 9781408837160

Pages: 304pp

Publication Date: 3 October 2023

RRP: $34.99