‘I only wanted to wear my dress of drab feathers and lie down and die, a bird that had lost the battle for the sweetest fruits’, Rosa Cassimati laments in Monique Truong’s work of historical fiction, The Sweetest Fruits.

The strengths of Truong’s novel lie in its arresting prose and how it defies a singular interpretation. At first glance, the novel is an account of the life of writer, Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904), as told from the perspective of the women in his life. Silenced, erased, and contorted — including by Hearn in his writings and the secrets he kept — Truong foregrounds the voices of the women. These women belonged to a global, racialised underclass of people suffocating under the disciplinary hand of British colonialism and imperialism.

Read: Exhibition review: The view from Here, AGWA

Rosa Cassimati was Hearn’s mother. Alethea Foley, a biracial woman born into slavery in Kentucky, was his first wife. Koizumi Setsu, a Japanese woman, was his second wife. His father Charles was an Irishmen and British Army surgeon. Rosa and her son were separated when he was an infant. She knew less of him than his wives, yet so much more than they could have hoped. Together, their accounts of Hearn struggle to provide a complete picture of the man.

At second glance, Truong’s novel is an account of the women’s lives. Here, Hearn is incidental, reducible to a thread weaving together the women’s stories. Through their recollections of him — ‘reminiscences’ — their agency is rescued from the historical dustbin. Each woman has a dedicated chapter, and we learn more about her respective desires, sorrows, and life than we do about Hearn.

At third glance, Truong’s tale is about the women and Hearn, and it is impossible to emphasise the former over the latter. In this tale, the four of them forged impossible and unimaginable bonds, bound together by distance, mobility, and proximity in equal measure. The gendered, racialised and class hierarchies that underpinned the deepening of globalisation and enabled Hearn’s globetrotting in the 19th and 20th centuries brought their ties to life.

The novel is the sum total of these interpretations, which refuse to be disentangled. Some readers may regard this as a weakness but in Truong’s hands it is the mark of superb writing. That Truong has written a novel through which she uses Rosa, Alethea, and Setsu to narrate Hearn’s story highlights several things. Her narrative reveals the fragility of memory — who gets to be remembered and why? It invites the reader to reflect on the importance of listening, who we choose to hear, and why. It makes one wonder about the possibility of making ourselves legible and sensible to others. That is, of painting a complete and true picture of a life.

The Sweetest Fruits is a novel about the essentially contested nature of truth. It is also about the impacts of intergenerational inheritances — trauma, loss, love — on generations past and present. It reveals the strength and impotence of borders and social hierarchies as Truong narrates and imagines Hearn’s impacts — like his father before him — on the women in his life. Truong manages to ‘save’ these women’s voices because in Setsu’s words, ‘There are fewer ways to save a life than you would think’.

Truong’s novel demands that the reader pause, listen, and digest before proceeding to the next chapter. Here, the author’s haunting use of metaphor will have the reader running back in no time, hungry for more.

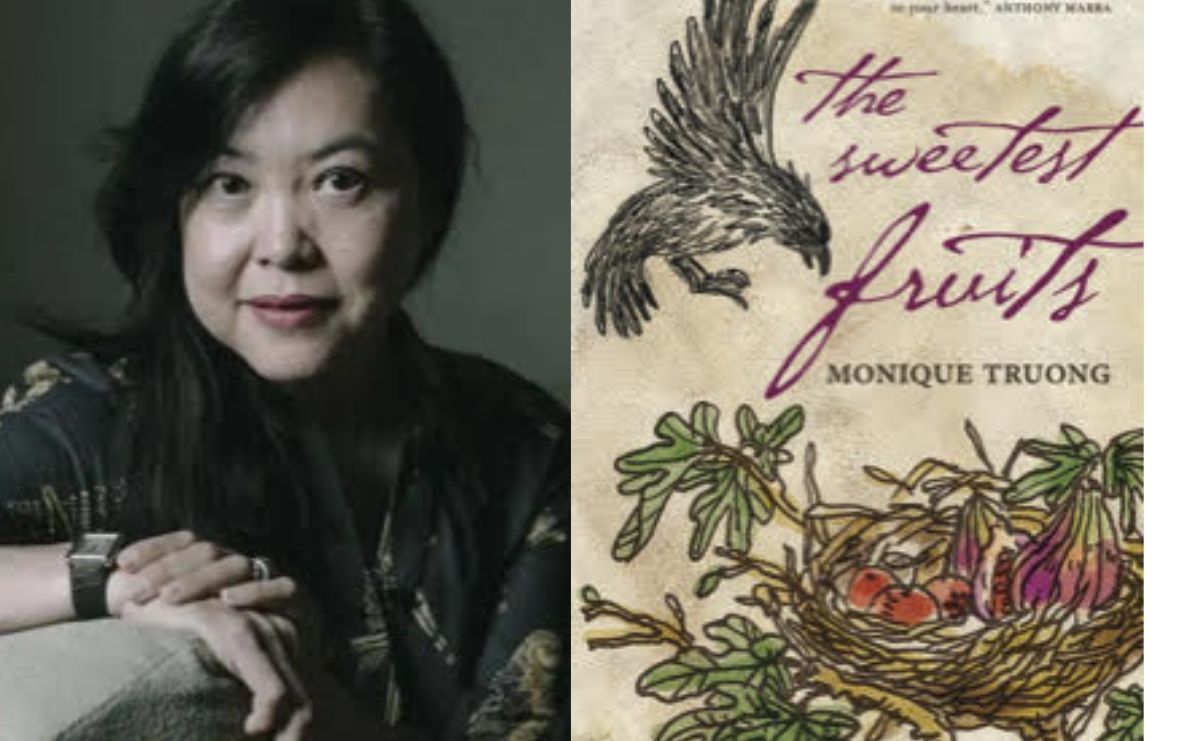

The Sweetest Fruits by Monique Truong

Publisher: Upswell Publishing

ISBN: 9780645076325

Format: Paperback

Pages: 310pp

Release date: 31 August 2021

RRP: $29.99