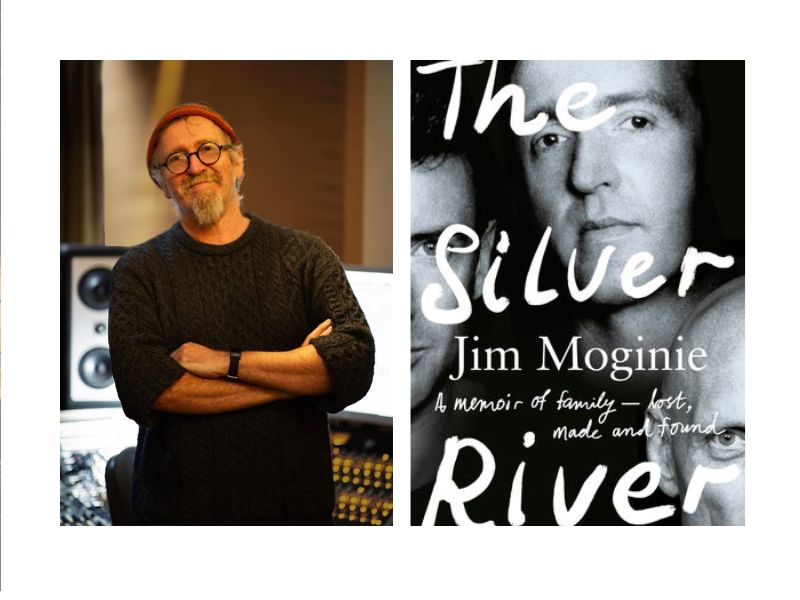

Midnight Oil’s songwriter, guitarist and piano guy, Jim Moginie infuses his page-turner memoir with all the bed bugs, microwave food and endless minutiae of life on the road.

In a tale that unfolds over many decades, the band turns newspaper headlines into famous lyrics, like ‘US Forces give a nod’. They sing to the hypocrisy of Anzac Day, to the farce of armistice and nuclear disarmament. Before Midnight Oil’s spin at the global record player times out, the band sells more than 20 million albums of protest songs.

Moginie creates the sound of Midnight Oil’s Outside World, ‘lying in bed at View Street watching the gum trees sway gently in the breeze on the night’. But there’s something happening to his inside world as well.

Divorced from his wife, his band and his mates, Moginie visits a Polish therapist, who starts flashing an Eveready Dolphin around in the dark, looking for what Moginie calls the ‘missing cog in my anthropoid clockwork’.

The band pushes straight into the aorta of a generation slowly awakening to the climate crisis and a world clogged with social injustice. During the Sydney Olympics, Midnight Oil perform for a TV audience of 3.5 billion, dressed in the word “sorry”, when Prime Minister John Howard refused to apologise to First Nations people.

But as the band pull on the handbrake of global touring, Moginie falls from the last Tarago at the end of the last gig and lands with a dull thunk. He has lost the “engine room” of Midnight Oil’s drummer and co-songwriter, Rob Hirst; he can no longer sketch ideas on cassette tapes for Peter Garrett to turn into Maralinga moments. And he begins exploring a deeper riff…

Mogine dedicates The Silver River, ‘to the mothers’, who he says have a chemical link to their children, even sharing the same psychology. When the bond is severed at birth, he says, the consequences linger on for life.

Behind a safe middle class family, Moginie’s secret is unravelling. He soon finds “infant trauma” isn’t a comfortable place to revisit, as he starts to deal with the emotional effects and symptoms ‘similar to post-traumatic stress disorder,’ and the lifelong impact of being adopted.

After being told he appeared traumatised as a child, he sees the links. ‘It seemed like a cobweb-covered rabbit hole of intrepid exploration under crumbling earth. But my hunch was that it informed my behaviour in adult life.’

His unmarried parents had been told there was no choice but to leave their baby behind in Sydney, go back to regional New South Wales and forget. As was common in Australia’s past adoption practices, Moginie waited for a new family, alone in an orphanage, in what he describes as a ‘brutal bisection’.

In therapy, half a century after he had been left behind in Sydney, he prepares to meet his birth family, declaring this is ‘my last afternoon as myself’. He meets his mother, his father and five siblings, who never knew he existed.

Moginie never sentimentalises. Instead he approaches adoption as a pragmatist applying radical acceptance. Through John Lennon’s music, he senses the shame of a generation of unmarried women coerced into handing over their children – many in stable relationships like his parents, Brian and Anne.

At a moment of uncertainty on their return to Queanbeyan, they had wondered if they should go back for him, but it was rare for a surrendered child to be returned. Moginie unfolds the PTSD he seems to share with his mother as a result of the separation and his face relaxes as the family tree is redrawn ‘in the shape of a triangle’.

In between stints with Midnight Oil, Moginie collaborates with some of Australia’s greatest talents –continuing with Rob Hirst, as well as Hamish Stuart, Liz Stringer, Silverchair, the Warumpi Band and Neil Finn. He also succumbs to an irresistible pilgrimage towards traditional Irish music.

At times he allows his prose to lilt like his drifty solo album Murmurations. This is music that starts out with no defined end, opening up an idea, then moving on to the next motif as the days of the week go by, leaving the past and many questions unresolved – an approach that flows into The Silver River.

On the page, Moginie allows his attention to wander, a device that avoids the claustrophobia that sometimes haunts traumatic storytelling. It demonstrates creative process in its raw form, the capturing of an idea, a sentiment, a song, a story, a life, then presenting it in media res.

In a future project Moginie may lean more fully into the poetic; perhaps he may join the growing canon of adoptee poets such as John Gallaher and Tiana Nobile, whose stories shine a light into the complexities of adoption.

Read: Exhibition review: good grief, Danish Quapoor, Pinnacles Gallery

After decades of service to pleasing the machine, the industry and the audience, Moginie no longer seeks to play it any other way than the way he hears it, and the way he hears it has resonance for anyone with a tender heart for stories of the Australian landscape – especially stories that depict the music scene and give voice to the many untold stories of Australia’s past adoption practices.

The Silver River, Jim Moginie

Publisher: HarperCollins

ISBN: 9781460765852

Format: Paperback

Pages: 256 pp

Publication date: 6 March 2024

RRP: $34.99