Before there were flashy cooking shows on television networks, there were other, more genteel approaches to cooking. There were Bills of Fare and Receipts – Recipes in French, which were handed down in upstairs-downstairs styled establishments throughout 19th century Europe.

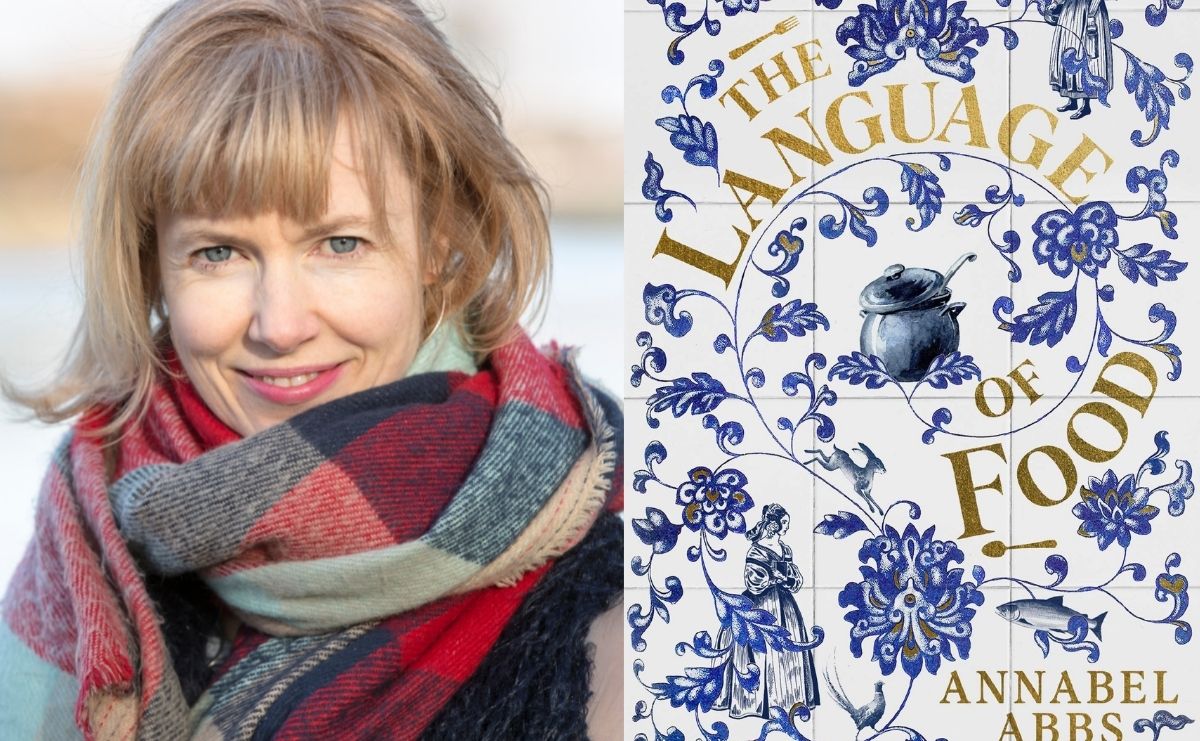

In an earlier novel, historical fiction author Annabel Abbs turned her attention to the ‘real’ Lady Chatterly, to critical acclaim. She has now rolled her lifelong passion for collecting recipes into a novel based on the life of Eliza Acton.

Published in 1826 as a poet, Acton spends a decade painstakingly creating her next volume, only to be told by her boorish publisher that people don’t want poetry written by women. She is sent home to write a cookbook instead, and when she complains, she is met with the back-handed compliment, that ‘a recipe can be as beautiful as a poem’.

Though quick to concoct with a quill in hand, she can’t cook a quail. Neither can she boil an egg.

She decides her editor is a buffoon, and pushes around a line of poetry, ‘and the sun like a vast golden orb in a dome of unbroken blue’, before teaming up with aspiring young cook Ann Kirby. Together they share and shape the narrative of The Language of Food.

Words that have departed the lexicon like ‘Michelmas’ and ‘somnambulist’ push the tale along, rather than weighing it down like a heavy sauce on a hot day, as Abbs wanders effortlessly through the archive of time. For Acton, this was an easier task, since she left behind scraps, notes and papers; research that Abbs folds neatly into the story, rather than laying it out self-consciously and cold on a plate. For Kirby however, very little is known.

Though she’s the woman with the talent for food, Kirby is not mentioned at all when Modern Cookery for Private Families is published. This novel, then, is a story of class. But it is equally a story of gender, for if Acton were a man, like her contemporaries Keats and Wordsworth, she would not have been banished to the kitchen.

Read: Book review: Loveland, Robert Lukins

Discovering that ‘blasphemy is in a sip of coffee’, Acton sneaks off to read mail from a poetry publisher, the way another woman may have snuck off to read correspondence from a lover. When an offer to publish arrives, it is as though the times have come full circle: she is ecstatic just to be published, accepting the terms of ‘no payment at all’.

She closes her reference books in despair, finding them only useful for feasts, one of which requires 24 eggs for a sponge cake. Then she writes the modern cookbook, with methods on how to choose a fish still favoured today: clear eyes, fresh smell, gills clear and red.

Yet it is the chapter titles which hold the most intrigue, drawn from Acton’s Modern Cookery, which sold 125,000 copies: Boiled Eels with Sage, German Style. Mauritian Chutney. Ortolans Garnished with Cocks’ Combs.

Though much is made of their day-to- day lives, little is made of the procurement of ingredients, or the work of storing and preserving without electric fridges and freezers. Similarly, the methods of production, and the stories of interesting characters supplying the kitchen do not take centre stage.

Where the drama focuses on food it is the most enticing: ‘I am pulling an iron tray of potato rolls from the oven straining to see if the crusts are sufficiently browned and crispy when the kitchen maid appears. Her hands scrambling at the ribbons of her apron, she cries out in surprise for the mantel clock shows it is barely six and the rush light throws only the splendorous beam upon my person.’ It is these and similar passages which will lure the reader into The Language of Food.

The Language of Food, Annabel Abs

Publisher: Simon and Schuster

ISBN: 9781398502239

Pages: 399pp

RRP: $32.99

Publication date: March 2022