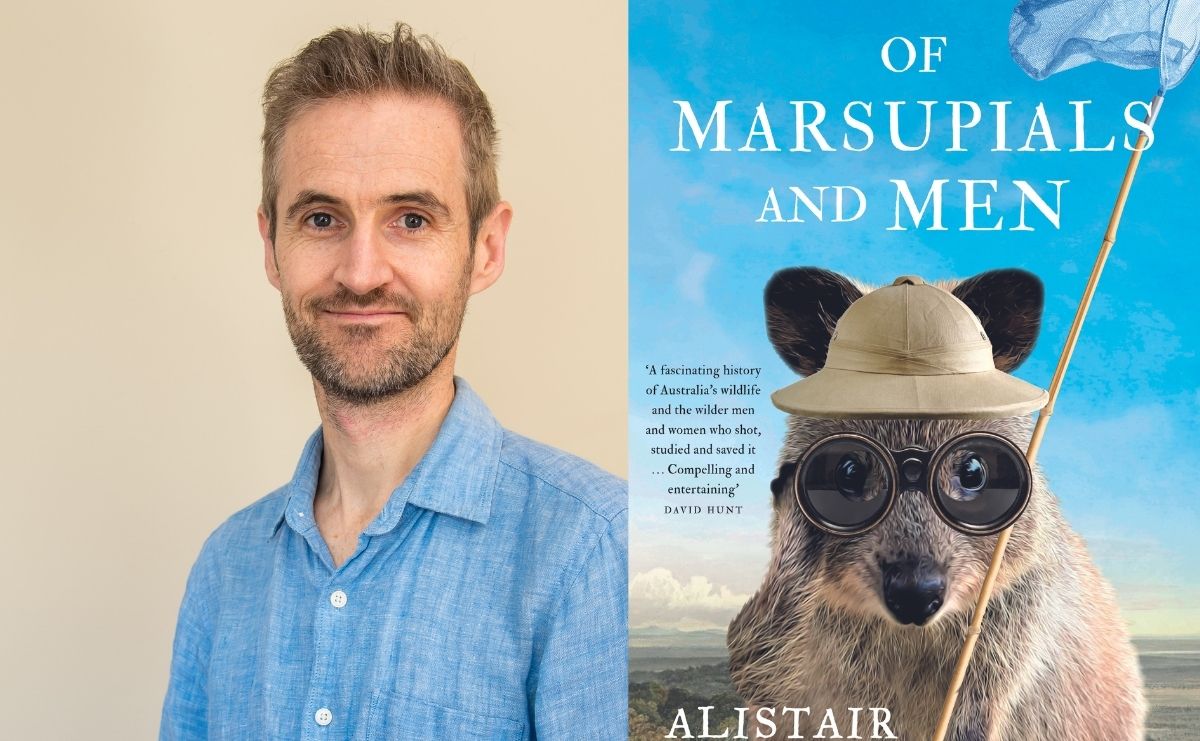

Of Marsupials and Men by Alistair Paton is a historical exploration of the (mostly) men who are to blame for the high rate of Australia’s species extinction, and the knowledge provided by the scientists and adventurers who sought – and continue to seek – to protect Australia’s wildlife.

For 21st century readers who are concerned about conservation, reading the stories of the early settlers may provoke anger at their beliefs and actions, which continue to ripple throughout Australia.

Even the revered John Gould, who with his wife Elizabeth and fellow naturalists, developed the tome Birds of Australia, was also part of the drive to shoot, stuff and ship the species that once teemed across this land.

Paton tells us that Gould is credited with ‘shooting the last pink robin seen in South Australia’. This is not to say these early explorers were the only ones responsible for our extinction rate, however, I would have liked some analysis of the impact of these early attitudes and actions.

Some early colonialists saw Australia’s wildlife as inferior or wrong, and sought to blast it out of existence, or make money from truckloads of pelts, or kill wildlife they thought threatened their sheep and crops. It’s difficult, as we try desperately to save the orange-bellied parrot, the Leadbeater’s possum, the growling grass frog and many more species, to see this text as simply ‘fascinating’, as the quote on the cover tells us.

A quote from Reverend Sydney Smith in the 1800s elucidates these early attitudes:

‘If we examine through the various regions of the earth, we shall find that all the most active, sprightly and useful quadrupeds have been gathered around man, and either serve his pleasure or still maintained their independence through their vigilance, their cunning or their industry. It is in the remote solitudes that we are to look for the helpless, deformed and monstrous works of nature…’

It’s not hard to also hear the damning views of First Nations people within this quote; to hear the reasons for the later policies of acclimatisation (bringing foreign animals to Australia to introduce culture or usefulness) and assimilation (which led to the stealing of First Nations children from their families, and further atrocities).

Although Paton occasionally mentions First Nations people in relation to their role on some of the expeditions – such as trying to save Burke and Wills, or passing on knowledge about ‘bush tucker’ to Alby Mangels – they are conspicuous by their absence. The book’s focus is European explorers, collectors, naturalists, scientists, hunters, traders, and media personalities.

I would have liked more research and stories on the relationship between First Nations people and wildlife. I expect this may have been challenging to achieve, but I think the text is poorer for the lack of these perspectives.

Having said all this, Paton’s research is impeccable and detailed, and the book is filled with interesting quotes, quirky details, and historical asides that bring to life the thoughts, beliefs, actions and stories of the past.

It’s a fast-paced exploration of the early colonial days through to the late 20th century, the lives and deaths of these men, and occasionally the contributions of their wives. Paton’s writing is lively, and he deftly spins a tale while also providing insights into life in different periods.

In this book you’ll read the stories of some of the men we can blame for our species loss, as well as the invasive species we’re still trying to contain. These men were venerated during their lives, and many are remembered through the names of species. This includes the Gouldian finch (named for John Gould, a beautiful brightly coloured bird now threatened with extinction) and Gilbert’s potoroo (named for his protégé John Gilbert), a critically endangered marsupial that recently made headlines as its numbers seem to be recovering after years of conservation efforts.

The early explorers were, by and large, men with financial means or backing to travel, shoot, stuff and ship species back to dusty halls in England, Germany and elsewhere. Many of these men were also difficult, cantankerous, and lived dangerously, sometimes becoming bankrupt, sometimes dying early deaths. They were not scientists, at least in the early years; rather, they were naturalists, men who explored and killed species in order to understand, document and describe them.

Like many other places that were newly explored by Europeans in the 17th and 18th centuries, Australia was a playground for adventurers, a place ripe for acclimatisation. Paton recounts efforts to introduce a wide range of species to Australia. If one early colonialist had had his way, we’d also be overrun by monkeys and antelope, as well as foxes and rabbits!

Paton writes, ‘The fundamental belief underlying acclimatisation was that all animals were created by God for the use of mankind. It was not only man’s duty to exploit them – it would be downright rude not to.’

In addition, there was a belief that the animals of Australia were ‘inherently deficient’. It’s not hard to see why we’re now leading the world in mammal extinctions. Even during their lifetime, some of these early explorers noted that some birds or marsupials started to disappear.

As the years progressed through the late 19th and early 20th century, the relationship between nature and the explorers changed from one of domination and curiosity to one of investigation and science. One entire chapter is dedicated to the ‘snake men’ who dived head-first, with wild adventurous spirits, into understanding some of the world’s most poisonous creatures. It’s thanks to these intrepid, daring, and at times foolhardy men that we now have anti-venom that saves many lives each year.

You’ll also read about why Winston Churchill had a stuffed platypus on his desk, how a German explorer named Gustav Weindorfer helped establish national parks in Tasmania, and how journalist Donald Macdonald ‘helped Australians to see their country in a new light’.

One of the longest stories is that of David Fleay, the man who captured footage of the last Tasmanian tiger, writing in beautiful detail that this ‘long, lean, softly padding animal had an ethereal appearance’. Fleay is also one of the men we have to thank for our understanding of platypuses, a man who loved animals and created what would later become the Healesville Sanctuary.

Paton also shines a light on at least four women who were naturalists, artists and scientists in their own right, including Elizabeth Gould, who painted hundreds of species for Gould’s various bird and mammal tomes.

He also shares the story of Mary Grant Roberts, whose early scientific work led to her displaying many native animals, saving Tasmanian tigers that had been trapped in snares, and establishing Hobart Zoo, where she changed people’s minds about ‘Beelzebub’s pup’ – or as we know them, the Tasmanian devil. He finishes up with stories about Valerie and Ron Taylor, whose underwater films were some of the first to show humans interacting with sharks, contributing some of the most shocking footage to the film Jaws.

Read: Book review: Holy Woman, Louise Omer

In ‘Epilogue: Not the End’, Paton brings us up to date with current efforts to save Australia’s extraordinary wildlife. He also finally adds a critical lens over the actions of those early explorers and collectors. Again, there is a missed opportunity in this text; at the end, Paton could have shone his light on the incredible work being undertaken by First Nations people across the country to share their cultural knowledge, address environmental issues, and protect and better understand the wildlife.

While Of Marsupials and Men is an enlightening, and yes, a fascinating read, bringing to life many interesting people who changed our understanding of Australia’s species, there are also missed opportunities to bring some balance to the text.

Of Marsupials and Men, Alistair Paton

Publisher: Black Inc

ISBN: 9781760643645

Pages: 304pp

Publication: 5 July 2022

RRP: $32.99