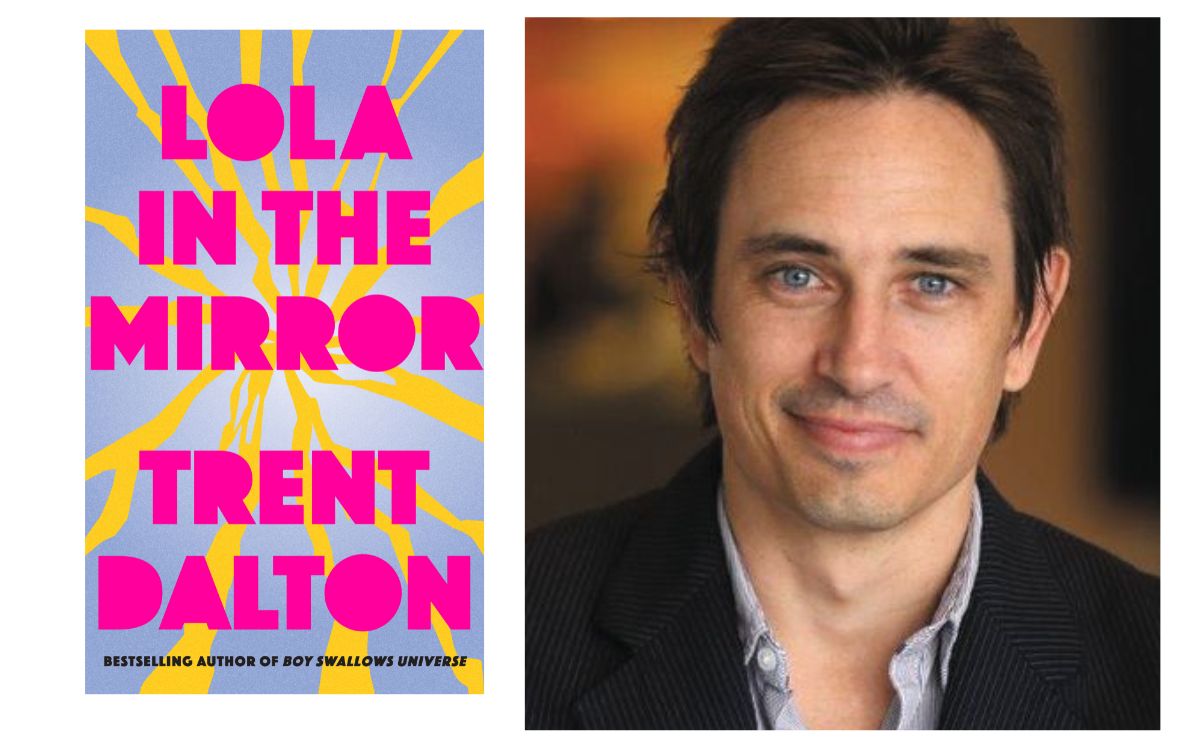

Trent Dalton’s books divide readers. You either fall for his heavy-hearted, larger than life characters and convoluted, magical realism detours or you think he’s overrated, mawkish and emotionally manipulative. In the end it really doesn’t matter; he’s a highly successful novelist in terms of units sold (his books have sold over 1.2 million copies in Australia alone) and his works are a bit of a rare beast insofar as they straddle the commercial and the literary.

His debut book, Boy Swallows Universe has been adapted for theatre and will soon be available on Netflix as a series. Whatever you think of Dalton, you simply cannot ignore the fact that he’s a publishing juggernaut.

Lola in the Mirror is his latest offering and, as he points out in the author’s notes, many of the events within it have been inspired by stories he has encountered in his day job as a social affairs journalist. Hence, he goes on to say, there are tales that depict violence, depiction and self-harm and yet, ‘Those same people I met in the street also spoke of community, hope and love, and that’s why I wrote this book.’

This novel is quintessential Dalton in that his detractors will find much to cast a withering eye over, while fans will celebrate his signature style of meshing real life and fanciful, imaginative flights. The protagonist is an unnamed 17-year-old on the run with her mother, after the older woman has become tired of doing ‘the Tyrannosaurus Waltz’ with her partner and left him with a paring knife in his neck.

Home for the nameless fugitives for the time being is a 1987 Toyota HiAce van with flat tyres parked in a scrapyard besides a river that smells ‘like a fish fart’. They prevail in straitened circumstances, thanks to the company and help of a stitched-together motley crew of other down-and-outers, “floaters” who are both poor and desperate, and some of whom are economic victims on waitlists for public housing. The postcode here is struggletown.

Set in and around Dalton’s home town in contemporary Brisbane (riverbanks, fish market, inner and outer suburbia), the two women encounter many other brutal tyrant lizards in the course of the book, with violence often biting at their heels, but there are also characters who, despite having lost in the lottery of life with few worldly goods to share, still cling on to decency.

Dalton has corralled the stories he has reported on as a journalist and fictionalised some of these case studies for Lola in the Mirror, particularly in his descriptions of the drop-in centre that takes in those who sleep rough in the city, and offers them food, advice and comfort. Here his feature writing rather than his novelistic flourishes come to the fore and he imbues the centre and its clients with the compassion and gravitas they deserve.

As with the author’s previous works, this one too centres on identity, with the truth drip fed throughout the course of the narrative. Throughout the book, the protagonist, an artist, dreams of having her drawings exhibited in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. She likes to refer to herself in the third-person, as though seen through the future eyes of an esteemed critic, and her black and white illustrations (actually by Paul Heppell) have titles like ‘Mum in the Jumper that Loves her Scars, Walking Silently by the Brisbane River’, ‘Petrol Station Attendant with Busted Lip’ and ‘But One Day You Will Dance with a Prince’. These pictures begin each chapter and set the tone for what’s to follow.

As for the title, the girl picks up a cracked mirror from the kerbside rubbish collection and sees the reflection of an older woman, at various times glammed up and in exotic locations (at the foot of the Eiffel Tower, near the ornamental garden in Shanghai…) and other times, a busted and woebegone creature in her bloodstained dress. It doesn’t take much psychological reckoning to realise that Lola is a doppelganger counterpart to the girl. A possible alter ego, depending on her choices in life and the vagaries of fate that she can’t control, Lola presents shards of different future pathways.

Read: Exhibition review: Justin Williams, COMA

Even as she’s pulled into the undertow of the criminal world with drug trafficking, there’s a stubbornness to her at the outset. ‘I ain’t homeless, I’m just houseless,’ she says. You are kept closely beside her the entire time, following her (mis)steps. In her smartness, loquaciousness and dreams for a better life, she shares the same DNA as those bright buttons in Dalton’s previous books: Eli Bell in Boy Swallows Universe and Molly Hook in All our Shimmering Skies.

There are times where the book tips over into hokey sentimentality – of course, the girl finds the purest incarnation of true love and the baddies are drawn heavy-handedly and in shades of black. Dalton is a writer who trades in magic, idealism and optimism, and hope is the one thing that can and does pull the girl out of the mire. The novel is a fairy tale that’s been rolled around in the detritus of the streets.

Lola in the Mirror fits in a number of topics; it’s an exploration of family dynamics, domestic violence, drug and alcohol addiction, housing crisis and criminal activities (which occupies similar territory to Boy Swallows Universe). There are both man-made and natural disasters within, lots of running and chasing, and also a couple of mysteries to unwrap. Enjoying Lola in the Mirror depends ultimately on your tolerance for big, sprawling, whimsical tales of good triumphing over evil with a population of Dickensian characters. It helps if you, like the girl in the book, believe art is transportive and love is salvation.

Lola in the Mirror, Trent Dalton

Publisher: HarperCollins

ISBN: 9781460759837

Paperback: 512pp

RRP: $32.99

Publication: 4 October 2023