Isn’t it wonderful, I think to myself, how a slight woman in the inner city suburbs of Melbourne, first derided by critics when she made her debut, has ended up anticipating the biggest literary trend of the 21st century?

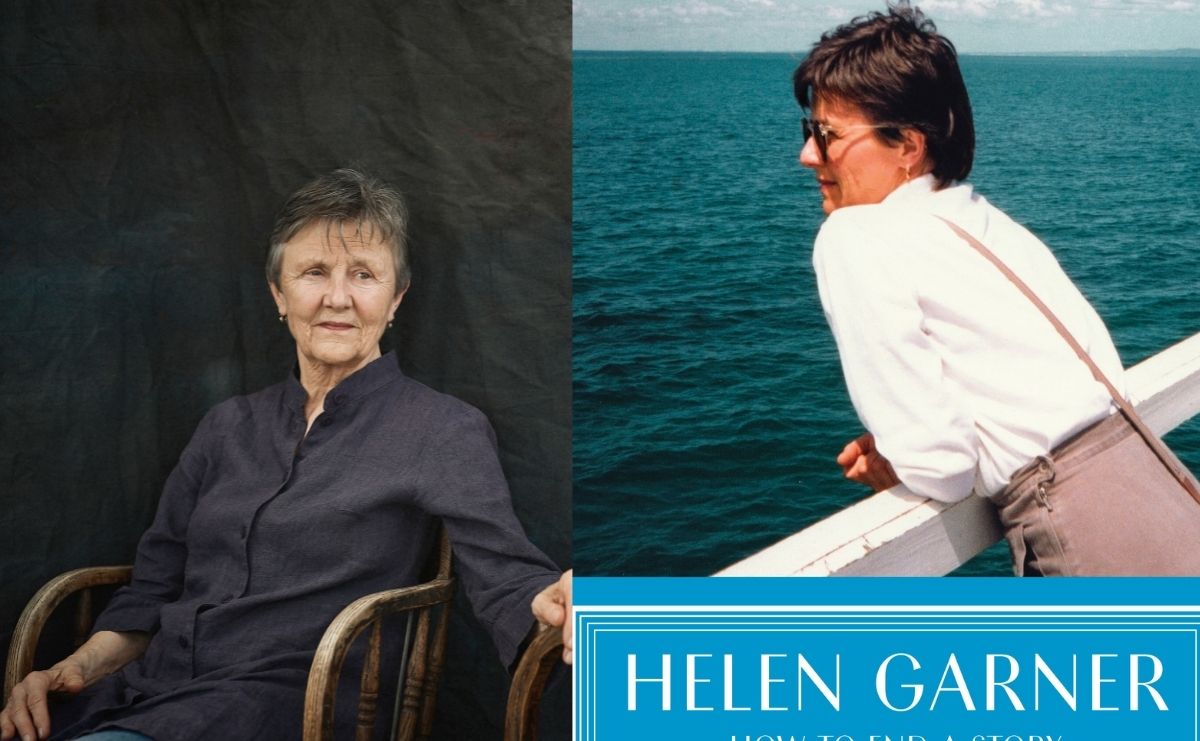

Helen Garner is a writer, a journalist, and a national treasure. Yet when her first novel Monkey Grip was published in 1977, she was patronised by an establishment hostile to the intimacy of first-person writing. The crime writer Peter Corris wrote that ‘Helen Garner had published her private journal rather than a novel.’ This charge, levelled cynically, has its own counter-intuitive genius. Decades later, in the essay anthology Everywhere I Look, in columns in The Monthly, and finally in a series of three volumes, the most recent of which, How To End A Story, has just been published, Garner steered into the skid and began publishing a version of her diaries. The results have the poignancy, the detail, and the generosity of Garner’s best writing.

How To End A Story: Diaries: 1995–1998, taps into a vein of autofiction that has become popular on a global scale. Starting with Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgaard’s Proustian lament for the fractured lives of writers, the My Struggle sequence, autofiction is a kind of overblown myth of the Everyman that tells us something profound about our narcissistic age. The comedy of self-deprecation and defeat, the frustration of deeply held desires, and the grand narratives of success are the bread and butter of stories that read like fragments from a life. If Garner has dressed the work she has been doing for decades in the clothes of these current fashions, it is not with an eye to literary greatness but an eye for detail, for the pearls and poignancy of every day life.

Read: Dance review: MindCon, Co3 Contemporary Dance

Helen Garner’s diaries and How To End A Story, its most dramatic volume, are in some ways similar and some ways different to Garner’s non-fiction. Where in Joe Cinque’s Consolation or This House of Grief, the ‘I’ that describes is performative, dramatising her own understanding of events as they pass and tend towards terrible tragedy, the ‘I’ in Garner’s diaries is genuine, a magpie scavenging for skerricks of pleasure. If the non-fiction recalls the late journalist Janet Malcolm, whose crime reportage like Iphigenia in Forest Hills has been an influence on Garner, then the autofiction follows in the tradition of 17th-century diarist Samuel Pepys who writes, like Garner, out of a debt to pleasure.

How To End A Story is pleasing to the reader precisely because of its courage. By this third volume in Garner’s diaries, the code she uses to offer privacy to the subjects of her diaries begins to become identifiable: we are witnessing the dissolution of her third marriage, to the writer Murray Bail. Like Knausgaard’s trilogy, it shares the perils of being married to a writer, and also, in some ways, an opposite personality, and a member of the opposite sex: he is theoretical, she is emotional. He thinks only of work while she longs for more.

Garner’s autofiction provides all the guts, glamour and goodness of the fiction that made her name. Its publication proves that the value of writing is firstly, for oneself.

How To End A Story: Diaries: 1995–1998, Helen Garner

Publisher: Text Publishing

ISBN: 9781922458179

Format: Hardback

Pages: 256pp

RRP $29.99

Published: November 2021