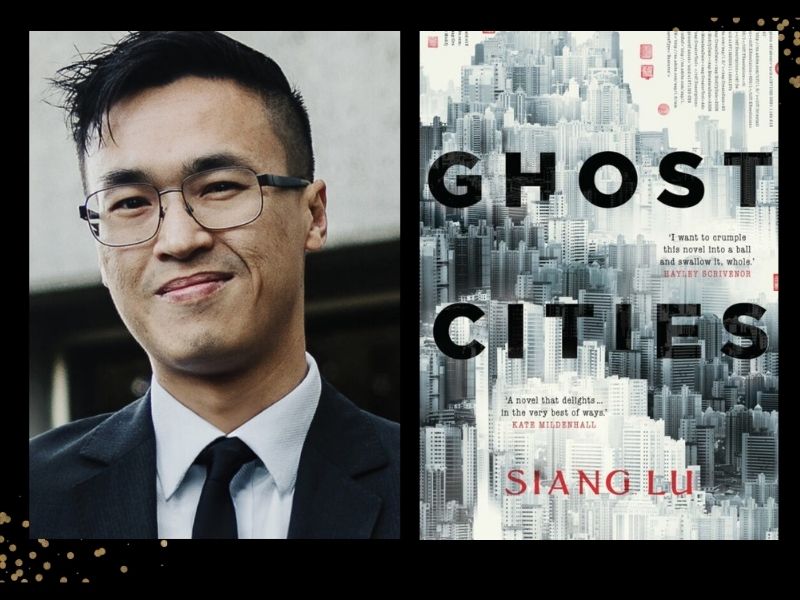

Modern political jargon notoriously insists upon the importance of “controlling the narrative”. In Ghost Cities by Siang Lu, we see meaning-making – stories, myths, translations – used to build, or subvert, power across the centuries. We see patterns repeat, the same dance between fact and fiction, the literal and figurative, and the same hubristic claims to lasting significance – the latter including empty megastructures in the Chinese countryside.

Lu’s book is an intricate tapestry of narratives – stories within stories about storytelling – that will beguile and reward those willing to engage with its patterns, shapes and form. Ambitious in its scope, Ghost Cities can feel enigmatic, almost coy – by turns bombastic then delicate, dizzyingly inscrutable then disarmingly matter-of-fact.

At its centre, is the powerful motif of the so-called “ghost-city”: large-scale, underoccupied developments in China, their eerie abandonment often perceived as testament to rapacious ambitions, the fairytale of prosperity.

In the main narrative a young man named Xiang is relocated from Sydney to one such (in this case fictional) ghost city, named Port Man Tou (the act of creation gleefully placed right there in its title) under the instruction of pompous director Baby Bao.

Lu’s enjoyably outlandish conceit overtly locates itself in the ephemeral realm of contemporary cultural meaning: Xiang, having been fired from his translator’s job at the Chinese Consulate for depending solely on Google Translate, has been launched to fame via the viral hashtag #BadChinese.

With this newfound cultural capital, our hero becomes the focus of attention for Bao, who wants to appropriate Xiang’s “power” for his latest project, a gargantuan epic that will use Port Man Tou as the world’s “largest film set”. Under the auspices of the Department of Verisimilitude, its citizens are background actors – creating a cityscape that Xiang realises is both “real and not real”.

The illusive, queasy, yet potent liminal third “space” or condition, between fact and fiction, how power plays with this uncertainty, feels key to the text. Meanwhile, the plot’s outlandishness, itself both real and not real, its joke at the expense of the individual (at us?), seems to be partly the point: mythologising churning itself into absurdity.

This example of modern day myth-making is intercut with tales from centuries earlier, an Empire also dependent on, ‘illusion – the slightest of sleights – that it had all been done before in another time by wiser and better men’.

Like Baby Bao, the emperor of this world is driven to arguably insane lengths to co-opt and draw power from his own story – such as destroying the Imperial Library and all its books, and Imperial decrees that officially sanction rumours about the punishment for his perceived enemies.

The innocent, fable-like quality of these stories beautifully offsets the breadth of imagination, dark humour, as well as the complex (and admittedly sometimes perplexing) interconnectivity, at play.

Within this complexity, a thematic thread of meaning-making, myth-making (and busting), and identity can be perceived: from the image of the emperor’s concubine Wuer, for example, who dedicates herself to recreating the books the Emperor destroyed, to that of village gossip Yang Ying, for whom recounting local news is always a process of adding weight and elaboration, steadily spinning truth into fiction, then fiction to myth.

Placed within this context, Xiang’s narrative centres the somewhat bewildered human in the midst of centuries, past and future and their attempts to forge an individual identity in a way that is both mordantly funny and oddly poignant.

It is, of course, an intrinsically Chinese story: one that concerns, more specifically, as Xiang describes it, ‘the China of our imagination’ – and in that respect it can seem quite caustic, albeit infused with compassion for its citizens. Still, it also feels particularly relevant more broadly in this, the year of a US election that stars ageing totemic behemoths slugging it out for the self-mythologised soul of their country (not to mention the shifting dynamics with China that this outcome may mean).

As we are taken through narratives that often interact with the lightest thematic touch, it’s true Lu’s work may at times disorientate or frustrate those looking for the hooks of narrative tension and character development.

Its most obviously accessible element is Xiang’s romance with Yuan – his translator, ironically, the conduit to understanding and, perhaps, self-determination. But even this too, feels strangely inscrutable – as the mouthpiece, at times, of Baby Bao we’re not completely sure what is true about Yuan and what is not.

Read: Book review: Murder in Punch Lane, Jane Sullivan

Nevertheless, it is apt for a work that is often concerned with the strange, playful yet potent liminal space between the real and unreal, the point of translation between the literal and more figurative (and back again), not to make its intentions too clear, to make the romance too neat. Those wishing to dwell in the impressive Ghost Cities, to explore its labyrinthine qualities, will be rewarded by finding patterns in its beauty, and building meaning of their own.

Ghost Cities, Siang Lu

Publisher: UQP

ISBN: 9780702268496

Format: Paperback

Pages: 304pp

Release Date: 30 April 2024

RRP: $32.99