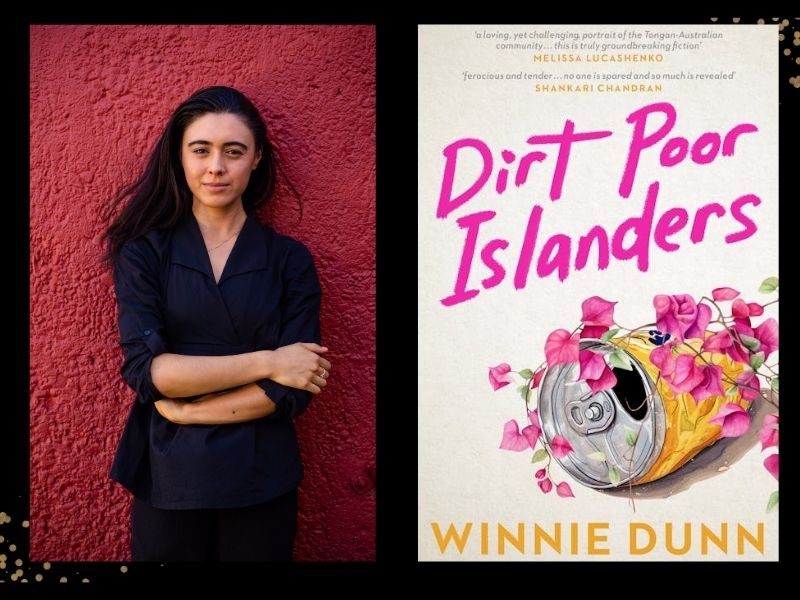

In her pioneering novel portraying the Tongan community in Australia, Winnie Dunn skillfully crafts a rich landscape that captivates readers with its vivid depiction of everyday life.

While Dirt Poor Islanders is Dunn’s debut novel, she is no stranger to the literary world. As the General Manager of the Sweatshop Literary Movement she has been widely published in Australia and is the editor of the acclaimed anthology Another Australian.

The novel has a classic Aussie backdrop in the Western Sydney suburb of Mount Druitt, where the reader is plunged into a familiar exchange for most diasporic people. When a pālangi neighbour, Shazza says, ‘Pack your hula-hula crap and shove it’, the subtext presents a stark reality that challenges the notion of greener pastures for those who have traversed the Pacific Ocean.

This is where we meet Meadow Reed, a half-Tongan and half-white pre-teen immersed in an intergenerational knowledge transfer from her wise grandmother, “Nana”. By teaching her granddaughter to paint a traditional rug called ngatu, she imparts cultural wisdom and nurtures a profound connection to their cultural heritage.

Like the author, Meadow is a writer who finds solace in words. When we meet her, she is in the middle of constructing a scene for her “gifted student” class.

Dirt Poor Islanders is divided into four parts: ‘Soil’, ‘Bark’, ‘Salt’ and ‘Blood’. Each segment opens with a powerful Tongan myth that also serves as a transition to illustrate Meadow’s life challenges.

The narrative employs talanoa – the Pacific Island method of conversation emphasising inclusive storytelling, listening, understanding, and collaboration for building relationships and making decisions collectively.

Throughout the offering, we witness Meadow’s evolution, originating in a place of introspective pain and leading to an innate detachment from her cultural roots. This is fuelled by the stigma of perceiving her people as unclean and inferior, particularly influenced by hurtful comments like those from Shazza. This pressure silently solidifies her desire to assimilate into Australian society, as she defensively asserts, ‘…but not me, not me, I was born here,’ ultimately leading to her decision to never again engage in painting ngatu with Nana.

The tale begins at number 4 Avery Street, better known as the house of Fe’ofa’aki, which means love one another. In this house, life experience unfolds in both English and Tongan because ‘it is what we’re made of, whiteness and dirt’.

In a plethora of themes explored, some are more subtle than others. There’s pride of selfhood shown through cultural motifs as seen on ngatu and body markings on Nana’s face and Meadow’s struggle with identity, where growing up Tongan in Australia is confusing because she is made up of many parts.

The politics of religion and culture can be a challenging theme to navigate. However, Dunn explores how Indigenous peoples’ beliefs and cultures have been erased. To hear about generations giving themselves up for Jesus is not easy. Meadow recalls the knowledge passed down by Nana who shared that ‘Tongans gave up tātatau, meaning tattoos, for Jesus, Tongans gave up our hair … Tongans gave up our land for Jesus … thank Jesus’.

Between thuds of footy played by her brothers to serious-talk whispers among the adults, much is discovered, including the sexuality of Meadow’s namesake auntie. This discovery inserts a deep worry about her own sexuality and the imminent choice when she arrives in heaven. Would God ask who Meadow chooses to join? Would it be her mummy Le’o who in some circles is considered to be without sin as a cisgender woman or would it be her sinful closeted lesbian auntie who is set to go to hell?

To elicit appreciation for what seems at times as a self-deprecating angle, the reader needs to acknowledge the author’s stance on artistic expression, as demonstrated in her TedEx talk. She says, ‘Our art is a reflection of our reality and our reality is our humanity.’

Dirt Poor Islanders emerges as a standout entry novel for being the first to present a historically marginalised community of people who demonstrate resilience, hard work and valuable contributions to society.

Dunn is unapologetic in the portrayal of her story, her people and their struggles but, most importantly, the beauty and rich culture that envelop them every step of their life journey.

Read: Theatre review: Things I Know to Be True, Theatre Works

The language is raw and honest without traces of political correctness to suit societal needs. This places the reader comfortably or uncomfortably within the characters’ time, space and overall existence.

Dirt Poor Islanders, Winnie Dunn

Publisher: Hachette Australia

ISBN: 9780733649264

Format: Paperback

Pages: 304pp

Published: 27 March 2024

RRP: $32.99