Grace Yee’s Chinese Fish is a reflection on the long white fog of colonial prejudice. Yee’s Chinese ancestors are reduced to alien heathens when New Zealand throws down its racist welcome mat.

Yee shifts both voices and forms in her wry autoethnographic poetry, offering a chronological map of her family as they slowly integrate into their chosen diaspora. Moving back and forth from Mongkok (Hong Kong) to Sydney and New Zealand, some relatives eat pineapple lumps and peanut slabs and wear Old Spice aftershave. Others retain their Asian identities, cultivating bonsai, collecting tiger balm tins and mah-jong cheat sheets. The touch is always light, despite presenting the brutal reality of the family’s lived experience.

Chinese Fish immerses hybrid Cantonese-Taishanese into English phrases, leaving the English-only reader to stumble across unfamiliar terms. The reader is expected to catch on, the way Yee’s family were, after landing on the docks in New Zealand. Only as a final appendix is any translation offered, by which stage the reader is so used to the frequent exclusion from meaning, that a literal understanding of what’s been missed becomes immaterial. It’s an effective dunk into the mental exhaustion of living in a culture that speaks a foreign language.

As the intergenerational story unfolds, news headlines are interspersed with lists and fragments of conversations, while Yee captures her family’s strict birthing traditions and cultural superstitions with her laconic ear for dialect.

The Cantonese characters become part of the story, as Yee explores the racist, sexist policies of early 20th century New Zealand. Legislation perpetuating the personification of the “chow” as a “vulgar monster” is reinforced from the backyard all the way down the street to the local fish and chip shop where her ancestors work for less than the minimum wage.

The Chinese are framed as a menace to the purity of the white races, while quotas ensure the preservation of white New Zealand policies, which were not particularly different to white Australian policies. Visits to Hong Kong were restricted to 72 hours, anyone else could travel overseas for three months. Little concern was raised over the impact such immigration policies imposed on family life. Children were sent to live elsewhere, much the same as they were under China’s one baby policies, when children were adopted by European families, while their mothers and fathers in China assumed their lost children were living somewhere nearby.

In Yee’s New Zealand, Chinese immigrants are characterised as unwashed lepers from unsanitary villages who are trying to infiltrate the Garden City paradise. Yet they are faced with daily doses of European food with the life cooked out of it, and left to clean “the s**t” from other people’s long johns.

Yee presents several pages of little boy and little girl icons, which challenge the racist view that the Chinese “all look the same”. As the family begins to integrate with the Pakeha community, stereotypes are reinforced in the playground, ensuring the next generation receives a fresh serve of racism in their daily lunchboxes. The family begin to take their tea with milk as a satirical menu offers a light-hearted spin-off with chops in every Western dish, from hot pot chops to chops with peas and chips. Meanwhile, in the gutters of the page, the Chinese market gardeners are fined for working at their calling on Sundays.

Asian women are characterised as “celestial satyrs”, while naturalised “Asiatics” are excluded from the aged pension, despite doing the dirty work for Westerners, from cooking, to cleaning and childminding. Phrases adapted from recent times all the way back to the 1890s appear in grey or cancelled out text, recording the cascading nightmare of what Yee’s family and many others endured; yet her gentle poetic style never becomes nostalgic or claustrophobic. She’s never accusatory, instead claiming the role of witness.

To feel, taste and smell these experiences is to wish for a better future, where the racism of both New Zealand and Australian culture is finally silenced, and the voice of every person is equally prioritised, from legislation all the way to the schoolyard. Only then might the homespun myths and phobias of “the other” fade from prominence, the way Yee’s legislative texts of old are presented in their faded print.

Read: Book review: A Light in the Dark, Allee Richards

Yee’s playful, insightful hybrid poetic memoir is an essential read that belongs in the syllabus for teaching future generations how not to do race and othering.

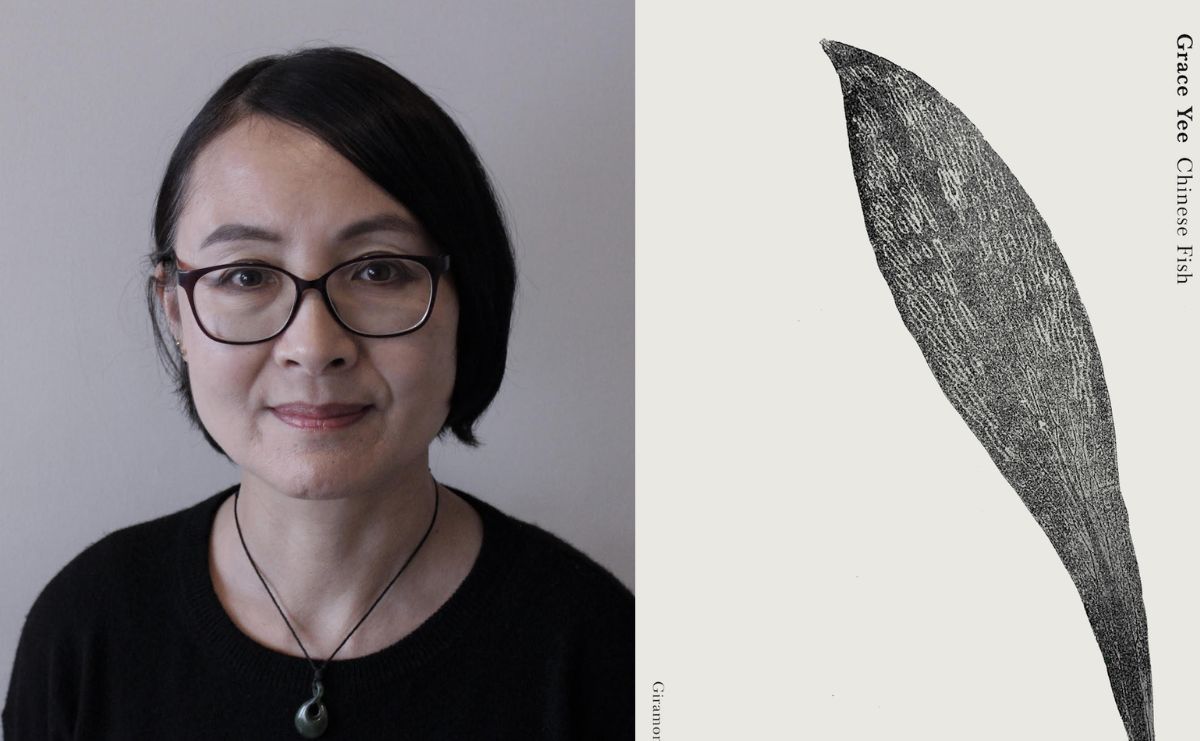

Chinese Fish, Grace Yee

Publisher: Giramondo Publishing

ISBN: 9781922725448

Pages: 144 pp

Publication Date: June 2023

RRP: $26.95