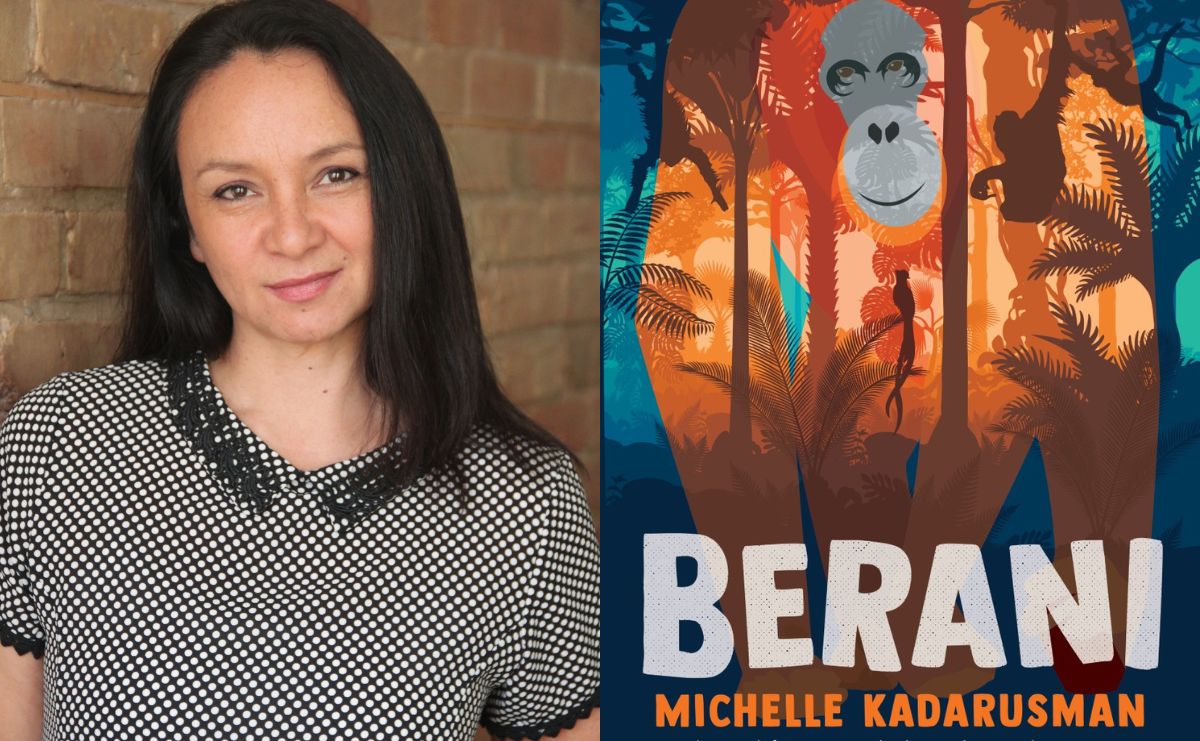

Berani, by Michelle Kadarusman, is an environmental tale for our times. In this sweet and heart-warming book, you’ll meet captive orangutan Ginger Juice and two young children, all living in Borneo and navigating environmental and socioeconomic challenges. Told from the perspectives of these three characters, Berani is part of a new crop of environmentally charged books aimed at middle grade readers aged between eight and 13. Some of the language and environmental messages may appeal, however, to readers of any age who are passionate about animal rights.

The two main human characters, Malia and Ari, sound (at times) typical of their age, with different levels of environmental consciousness and maturity. At times, however, their self-awareness is a little overblown. Here’s Ari:

At first, I was too busy balancing schoolwork and the restaurant chores. But then, when the opportunity and time presented itself, something else stopped me.

Guilt. Guilt stopped me.

How could I go back to the village and explain the wide horizon of experiences the city has opened for me?

Despite this unlikely level of perception and language proficiency, the children’s voices are beautifully written, and the characters are unique, showing the two sides to a significant environmental issue: the survival or possible extinction of orangutans. The children face some of the challenges that children in Indonesia may face, such as Ari’s guilt that his best friend and cousin Suni can’t go to school in the city because she’s a girl, and Malia’s struggles as an activist advocating for the labelling of palm oil within a country that relies heavily on sales of the divisive product.

In keeping with the expectations of books for this age group, there are educational messages, tension and conflict with adults, and children being heroes in their world. Although it’s written in English, the messages and themes are at times more relevant to an Indonesian audience, especially those who may not be aware of the law in relation to orangutans in captivity.

The situation of Ginger Juice, an orangutan held captive in a small cage in Ari’s uncle’s restaurant, is not unique in Borneo or the nearby island of Sumatra, and Ari’s growing awareness of her rights and the illegal nature of her captivity seem aimed at an Indonesian audience in the messaging.

More than anything, the book investigates and depicts the sociopolitical and economic influences affecting the children and Ginger Juice. The author, who has lived in Indonesia, Australia and Canada, reveals her inside knowledge about these conflicts, and depicts a nuanced, considered approach to the question of palm oil.

Possibly because of her personal knowledge and experience of Indonesian culture, she’s able to depict Ari’s Uncle Kus, who has kept Ginger Juice and black mynah bird Elvis Presley caged for most of their lives, as a multilayered character. He is not a villain, as many may be tempted to see him, or a cruel man, although his actions can be seen as cruel and have inflicted pain, especially on the orangutan.

It’s in the voice of Ginger Juice that Berani (which means ‘brave’ in Indonesian) really comes alive. While Malia is advocating loudly for the government to label products with palm oil and facing censure because of her actions, and Ari is discovering a new talent as a chess champion, Ginger Juice is the beating heart of the book. She watches the rain fall, remembers her time in the jungle with her mother (Ibu) and recounts the moments that led to her capture.

She uses similes inspired by nature to describe her world, such as calling Ari, who wears glasses, ‘Slow Loris boy’. When you first encounter it, Ginger Juice’s voice is heart-breaking and delightful, but as she descends into depression and gives up on life, we stop hearing her speak and it’s a tragedy. The final scenes and the climax of the two main story threads are, to avoid spoilers, satisfying and beautifully written.

Ginger Juice’s voice has slightly awkward syntax to demonstrate that she’s not human and, in this post-humanist text, it’s refreshing to read a perspective from an animal. May there be more such texts! Kadarusman has written other acclaimed environmental fiction books, including Girl of the Southern Sea and The Theory of Hummingbirds. I look forward to her next adventures into the lives, voices and hearts of animals, especially those who need humans to speak up on their behalf.

Read: Exhibition review: Adrián Villar Rojas: The End of Imagination

The final voice you hear should be Ginger Juice’s. Here she is, at the start of the book:

Drip. Drip. Drip.

Fat raindrops tap, tap, tap on fingers. Elvis Presley, black bird, sings secret songs. Song he crows when no human here. When human here, he moves up, down on perch and sings human words over and over.

When Elvis sings secret music, I remember birdsong from before-life. Scraps of sound and scent dance out of reach, same like butterflies used to flutter over nest. When Elvis Presley sings secret songs, I back in green, swaying world with smell of wet leaves and moss.

And you, Ibu. You there too.

Berani, Michelle Kadarusman

Publisher: Allen & Unwin

ISBN: 9781761068027

Format: Paperback

Pages: 224pp

Publication Date: 1 November 2022

RRP: $16.99