While Australia has no official language, English has generally functioned as the national language since the arrival of the British. According to the last census in 2021, 72% of the population speak only English at home.

But the English we speak in Australia began to diverge from British English almost immediately after the 11 ships of the First Fleet landed at Botany Bay in January 1788.

Shaped by a natural environment and social conditions that differed wildly from Britain, Australian English was always going to deviate from the English spoken on the other side of the planet.

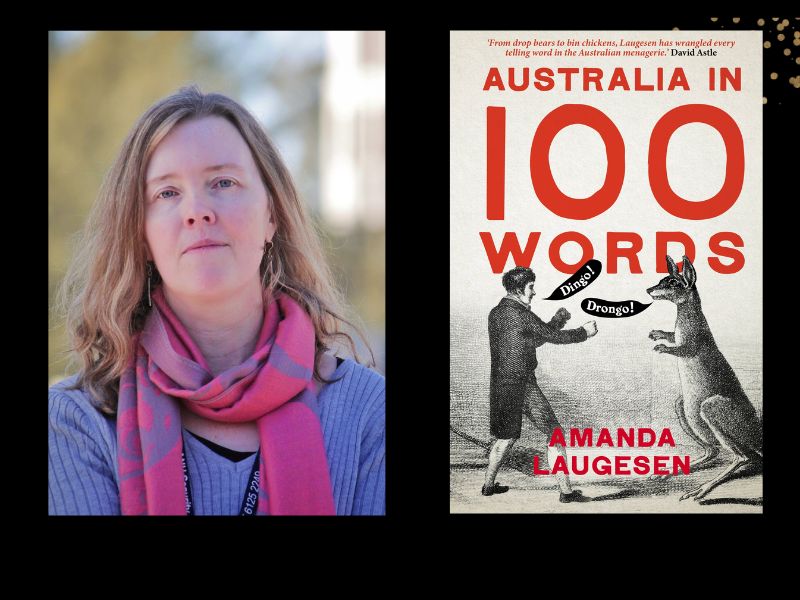

Historian, writer and lexicographer Amanda Laugesen explores these differences in Australia in 100 Words, from common, well-used examples like ‘mateship’ (‘the bond between equal partners or close friends), ‘bogan’ (‘an uncultured or unsophisticated person’) and ‘sickie’ (‘a day’s leave from work or school, especially taken without sufficient medical reason’) to more obscure words, such as ‘balanda’ (a non-Indigenous person of European descent’), ‘black mist’ (‘a black cloud of radioactive fallout that resulted from nuclear testing’) and ‘habib’ (‘a mode of address for someone considered a friend’, used mainly by Lebanese Australians).

Laugesen, the Director of the Australian National Dictionary Centre at the Australian National University and Chief Editor of the Australian National Dictionary, posits that many of our unique words have their origins in our convict past. Other words are archaic British English throwbacks, which long ago fell out of use in the ‘Mother Country’.

The book also contains words derived from Indigenous Australian languages, such as the aforementioned ‘balanda’, ‘gunyah’ (‘a temporary shelter usually made of sheets of bark and branches’) and ‘yidaki’ (‘an Aboriginal wind instrument’), as well as words rooted in Australia’s rich migrant heritage, including ‘habib’, ‘halal snack pack’ (‘a fast food dish consisting of hot chips, halal doner kebab meat, cheese and sauces’) and ‘New Australian’ (‘an immigrant to Australia, especially one whose first language is not English’).

It’s significant that the words explored here aren’t organised in alphabetical order. Instead, they’re presented in a linear fashion, correlating with the time these words appeared in the lexicon. This is fitting, as the book functions not only as an exploration of Australian English, but also as a history of the nation, especially its social and linguistic development.

Also notable is that while the book is called Australia in 100 Words, the entry for each word explores further related words. For example, under the entry for ‘greenie’ (the globally used word to denote ‘conservationist or environmentalist’, which originated in Australia) we also read about the origins of the term ‘black bans’ (‘a prohibition imposed by a trade union that prevents work from proceeding’) and ‘green bans’ (a similar type of ban on environmental or heritage grounds). Similarly, under the entry for ‘illywhacker’ (‘a small-time confidence trickster’) we learn about more Australian English synonyms for ‘illywhacker’ including ‘lurkman’, ‘magger’ and ‘rorter’.

Read: Book review: Dropping the Mask, Noni Hazlehurst

This approach means Australia in 100 Words is a far more extensive account of Australian English than may be assumed by its title: it’s more like ‘Australia in several hundred words’.

An impeccably researched book by an expert in the field, Australia in 100 Words is highly informative, written in an engaging, readable style and recommended for anyone interested in linguistics or Australian history.

Australia in 100 Words, Amanda Laugesen

Publisher: NewSouth Books

ISBN: 978142237909

Format: Paperback

Pages: 274 pp

Publication: 1 October 2024

RRP: $32.99