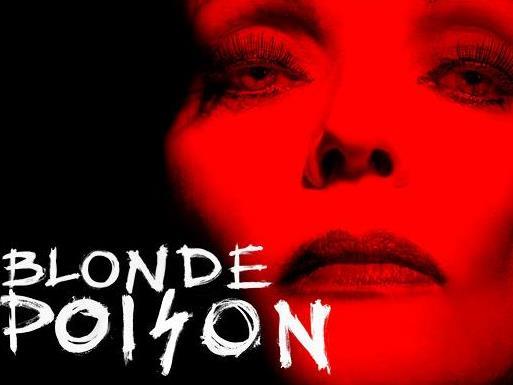

Image: Blonde Poison; courtesy of Sydney Opera House.

‘I was a queen’, says Stella Goldschlag about her time informing on Jews hiding from the Gestapo. ‘I was a boss. I was the one causing the vermin to hide’. ‘Blonde poison’ was the nickname given to Goldschlag for her efforts to lead the Nazis to about 3000 Jews during the Holocaust. The eponymous play bears witness to this elderly woman’s reflections on her time as a “greifer”, alone in her apartment as she waits for a childhood friend, now journalist, to interview her.

The monologue is a fascinating study in moral disengagement. The term refers to the ways people disable their moral codes to avoid feelings of shame and guilt about their immoral actions. Moral disengagement theory has been used to explain behaviour ranging from aggression in children, to bullying, cheating and corruption, to Australia’s treatment of asylum seekers and famously, to the behaviour of officers and citizens in Nazi Germany.

Goldschag uses three well-known techniques to minimise insufferable feelings of guilt. As a Jewish woman living illegally in Berlin, Goldschlag was betrayed and tortured. She then accepted the Gestapo’s offer to save herself and her parents from the death camps by using her insider knowledge of the Jewish community to expose them. She tries to convince herself that her actions were morally justified: ‘I only did it to save my parents’.

Next she diffuses responsibility for her actions onto others. She wasn’t to blame for the Jews she condemned to Auschwitz – it was the fault of the Wehrmacht soldier who joined her on the mission to find Jews in hiding. She says ‘I only accompanied him…it was only me by association’. He took them, he stole their watches, and he became rich. He was the evil rich one and she is oh so different: ‘I’m poor, I live on social security benefits’. Absolving herself of guilt, she sees herself as an innocent victim: ‘I’m a victim of Nazism. I should receive compensation’.

Her most powerful technique is dehumanisation. The monologue is riddled with language to disown her background and ‘other’ the Jews. She says we had culture, they had black hats, we were blonde and smart, and they had yellow stars. Goldschlag identified more with the Nazi soldiers who were ‘smart, clean…tall, straight’ than the ‘disgusting’ Jews. She loved when people saw her blonde hair and blue eyes and said she was ‘so not Jewish. Yes, that was the compliment I liked to hear the most.’ It’s easier to live with yourself if you see your victims as ‘vermin’.

Blonde Poison works both because of its confronting psychological insights into human immorality and thanks to a stellar performance by Belinda Giblin. Giblin fully inhabits Goldschlag’s complexities. Yes she is painfully vain and narcissistic, constantly admiring her youthful appearance and telling us how much everyone loved her. Yet she’s also desperate for her parent’s affection: ‘You are proud of me aren’t you Mutti?’. She sees herself as the ‘font of all knowledge’ and constantly returns to her magnificent beauty, but she’s also tired and afraid. Though she’s repellent when she brags about catching Jews like a ‘little fly caught in my trap’, Giblin prevents blanket audience condemnation by portraying the intense fragility, weakness and loneliness beneath the old woman’s bravado.

It’s a heavy going monologue with some slow passages, much repetition and little relief. Yet Blonde Poison offers important insights into human psychology and a stunning portrayal of how pernicious systems and ideologies corrupt human morality.

Rating: 3.5 stars out of 5

Blonde Poison

By Gail Louw

Director: Jennifer Hagan

Designer: Derrick Cox

Lighting: Matthew Tunchon

Sound: Jeremy Silver

Starring Belinda Giblin

The Studio, Sydney Opera House

28 April – 12 May 2016