The degree to which music informs the emotional heft, depth and topography of film would come as no surprise to filmmakers or screen composers, but seeing that play out live certainly, um, underscores the point for those of us who are neither of those things.

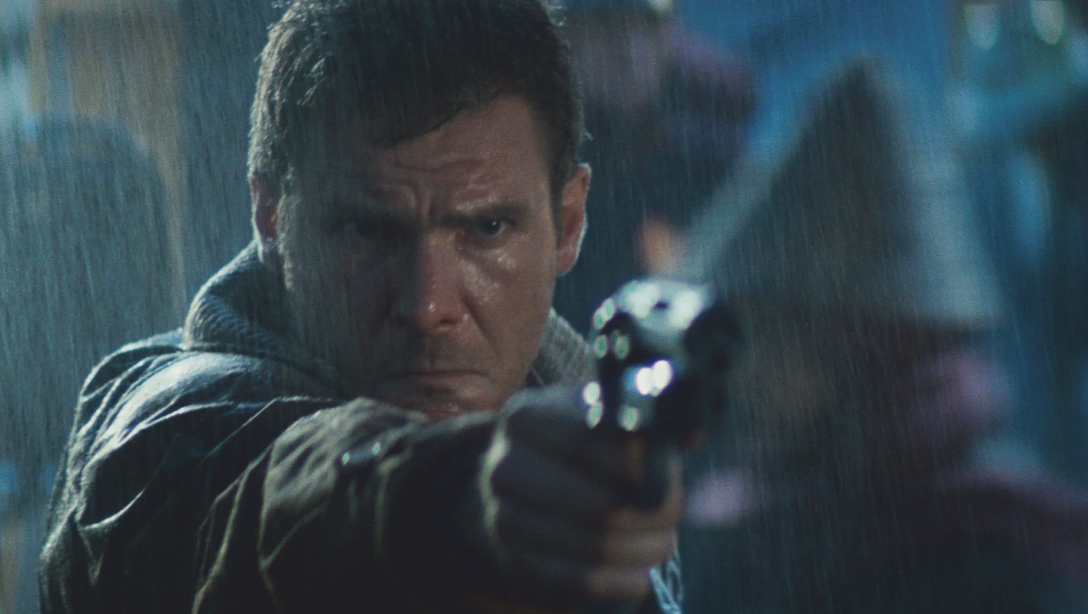

And so it was with Blade Runner Live at Hamer Hall in Melbourne on Saturday evening: a screening of Ridley Scott’s 1982 sci-fi classic starring Harrison Ford, Sean Young, Rutger Hauer and Daryl Hannah, its synth-led soundtrack performed in synch with the film by the Avex Ensemble.

Prior to the opening credits, the 11-piece ensemble (to appreciative applause) played the production company’s jingle as The Ladd Company’s logo appeared on screen, followed by the first heavy thump and echoing rumble of the score by the late Greek electronic musician Vangelis.

Already, before the film’s opening text explains where and when we are – Los Angeles in 2019, where robots known as Replicants created by the Tyrell Corporation have advanced to such a degree that they’re now ‘virtually identical to a human’ – Vangelis’ score is as melancholy and evocative of an atomised dystopia as the film’s ceaseless rain and rubbish-strewn streets, foreshadowing a story that’s as much film noir as it is sci-fi.

Performed live, those unsettling low-end rumbles, high string-like synth lines and eerily descending single notes set up much of what is to come.

Like Scott’s film, the score – performed flawlessly by the ensemble on the night this reviewer attended – pulls off a deft trick, creating a sense of intimacy (this is no John Williams’ orchestra) while conjuring a world (and indeed those never-seen Off-World colonies) that stretches into alternative realities our eyes and ears will never encounter: a close palette that conjures an almost infinite canvas.

As a contemporary viewer, it’s as mind-bending as the film itself to reflect that we’re watching the 2007 Final Cut of a 1982 movie set in 2019 that’s based on a novel (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?) by Philip K. Dick published in 1968.

The most surprising part isn’t the obvious predictions that didn’t come to pass (flying cars are still, sadly, not available) but those that did: there’s no mention of the global nuclear war that forms the premise for Dick’s novel, but this is still a world ravaged by a climate catastrophe, as signalled by the non-stop rain in the famously water-starved Los Angeles.

Also still very much relevant are the questions raised by artificial intelligence. What does AI mean for us? How might it change us? And, just as profoundly, how might AI itself change as it develops the self-awareness to consider its own morality and mortality, and how might those two quintessentially human concerns interact?

As Gaff (Edward James Olmos) says to (human/replicant) Deckard (Ford) near the end of the film, in relation to Deckard’s love for Rachael (Young): ‘Too bad she won’t live – but then again, who does?’

The love story between Rachael and Deckard has, of course, been a point of discussion since the first-ever screenings of the film, but inevitably lands differently for viewers in 2023, especially during its central ‘romantic’ moment, scored by Vangelis’ Love Theme.

Afraid and vulnerable, Rachael (a Replicant, we have to remind ourselves) tries to leave Deckard’s 97th-floor apartment but is prevented by Deckard, who blocks the door before throwing her against the wall, the score’s momentarily sinister synth line giving way to a soft-porn steamy sax as Deckard kisses Rachael then commands her, even as her tears spill, to say ‘kiss me’ and ‘I want you’. In terms of sexual politics, it’s complex, to put it mildly, and hearing the raunchy sax spill out in all its glory across Hamer Hall didn’t make it any less so during this screening.

Read: Video work review: Angela Tiatia: The Dark Current, ACMI

With the BAFTA and Golden Globe soundtrack not released – and even then, incompletely – until 12 years after the film, and with various other iterations appearing over the years, debate about the ‘authentic’ version of the score mirrors the seven different cuts of the film that have been shown variously to test audiences and cinema-goers over the decades. And, of course, it mirrors a couple of the deepest and most enduring questions presented by the film: what is the ‘real version’ of anything anyway, and who, ultimately, gets to decide?

Saturday evening’s screening was the first time I’ve seen Blade Runner on the big screen, but maybe the tenth time overall, and while I’ve enjoyed every one of those viewings, none hit with the emotional force of Blade Runner Live. Naturally, that’s down in no small part to the film – but also, more than I’d realised, thanks to the Vangelis score, performed here pitch-perfectly by the Avex Ensemble.

Blade Runner Live screened at the Hamer Hall Melbourne on 4 November 2023.