Brown writes with a lively voice, juxtaposing thoughts and events to produce an easy-to-read account of his African posting. He uses contrast as a foundation for his narrative, mirroring his emotional roller coaster ride. He sets his day-to-day domestic interactions with fellow volunteers against the incredible background of a nation recovering from 27 years of civil war: “… even this front courtyard, entered via the crooked gate to our right, a No Guns sign tacked above, is unlike anything I’ve seen. Traditional village, grim medical centre, happy child play-centre, last hope for the desperately poor – it’s all of these, everything in between.” He bounces from joyful events – the recovery of a malnourished child – to the heartbreak he feels when confronted with a patient who will die from a preventable disease.

At times, Brown becomes introspective: “… Poverty this extreme can’t be quantified. It’s a state of existence. Hollow cheeks, four skinny limbs and a belly swollen with parasites; patches of ringworm causing bald spots all over these kids. And it’s why I’m here, I’ve decided…” He writes about searching for an explanation when a patient dies, his frustrations and losing sleep through worry. It’s easy to imagine writing as his therapy, his way of coming to terms with what he witnesses.

Brown notes that ‘bearing witness’ derives from the French term témoignage, which is one of Médecins Sans Frontières’ central tenets. As part of their operations in a troubled country, they note the testimony of affected locals, creating a record of the atrocities or conditions that gave rise to the MSF presence. In many ways Brown’s book is his own testimony, his record of how working for MSF affected him. At times he questions the decisions of the organisation, but is careful to avoid direct criticism. He admires their volunteers, particularly the ‘logs’ (logistics personnel), “… who are responsible for all the maintenance, construction, communications and supply aspects of the project,” and without whom, he implies, the medics could not work.

There is a sense of immediacy throughout the book, created by Brown’s use of present tense. He places the reader alongside him on the wards; he shares his thoughts over the removal of an appendix – in a theatre where lighting comes from a headlight wired to a car battery and the instruments are sterilised in boiling water over an open fire. Much of his prose is direct speech, resembling a novel, which may expand his audience to those who usually avoid non-fiction.

Given Brown’s subject matter, his story could easily have become a depressing account of the circumstances of those he assists. But even in the worst of situations, he writes of the beauty in his surroundings. Ultimately, Band-aid for a Broken Leg is a dissertation on dichotomies: modern and primitive medicine; wealth and poverty; developed and developing nations; generosity and avarice. But far from being a dry essay, it is a celebration of the ascension of human spirit in adversity.

Rating: 4 stars out of 5

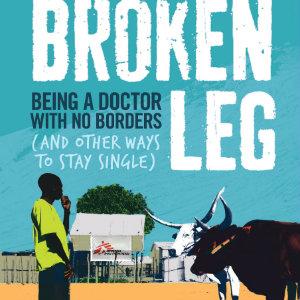

Band-aid for a Broken Leg: Being a doctor without borders (and other ways to stay single)

By Damien Brown

Paperback, 360 pp, RRP: $29.99

ISBN: 9781743310212

Allen & Unwin