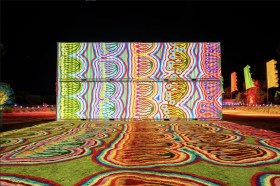

Detail / film still, The Calling (2013-2014) courtesy the artist

You can hear Angelica Mesiti’s exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) well before you can see it. Walking down the ramp to the lower contemporary gallery spaces, it is the sound of a lone, resonating whistle that seemingly calls you into the moment.

Appropriately titled, The Calling (2013-2014), it is the first of five video works by the Sydney-born Paris-based artist, in an exhibition that surveys her recent practice. The three channel video work has been proposed for acquisition, and beautifully captures Mesiti’s long held fascination for non-verbal communication and adapted forms of expression. Alongside this video that records a traditional language of whistling, the viewer is also introduced to dance, gesture, rhythm, signing, euphoria and intuition as effective modes of communicating.

In these times where we are stimulated more than ever by a deluge of words delivered via round-the-clock technology, Mesiti has the capacity to still us through her videos, and alert us to an awareness of our own non-verbal use of language. And while the thought of sitting through five video works might be a challenge for some gallery-goers, Mesiti makes it easy for us, allowing the viewer to find that point of familiarity, of connection – of communication.The Calling is a great place to start. Whistling reminds us of children’s play; I still like to whistle while I ride my bike. So while these locations in The Calling are completely foreign to our contemporary world – remote regions in Turkey, Greece and the Canary Islands where whistling has been used for centuries as a way to communicate – our DNA as humans is hard wired to creating stories as a way of navigating things. The entry point is easy.

In saying that, Mesiti has the ability to skate between documentary, a story telling vernacular and rich aesthetic framing to reinvigorate tradition with new life. While she has described these languages as ‘cultural artefacts’, she has also said that she is very aware that her videos are made for a gallery or museum context – and while they may borrow on the cinematic vernacular of story telling, that is not their main purpose. She is not on some mission of advocacy here to save language.

Mesiti’s position starts to make sense moving in and around this exhibition. It is very spatially alert.

Rapture (silent anthem) 2009; courtesy the artist

Impact is not always reliant on scale

An element of this exhibition that I really enjoyed was that you moved from this big three-channel expansive video work, The Calling, into space that was fragmented – a video is glimpsed from within a “white cube structure” that has been built in the gallery. It kind of beckons us over to this more intimate viewing space – but doesn’t give a lot a way – a bit like a good first date.

Off to the side, two flat screens are tucked away in a dead spot of the gallery’s architecture. They had no sound; there was no punchy call to come and watch, and yet these two works were like Venus Fly Traps that caught you, bewitched you and had you fully engaged after just a sideways glance.

The slow motion hair dance, Nakh Removed 2015, reimagines a Berber ritual which was performed in the traditional wedding season. Its trance-like, hypnotic rhythms have been transported to a contemporary dance studio.

Nakh Removed, 2015 (extract) from Angelica Mesiti on Vimeo.

The second is another video without sound. First presented for the Blake Religious Prize, Rapture (silent anthem) 2009 captures that euphoric state between the religious and secular as fresh-faced teenagers are filmed in a rock concert mosh pit. They are lost in worship and collective fervour.Moving back into that custom gallery-within-a-gallery, visitors walk up a ramp and enter the space to be surrounded by the four-channel work, Citizens Band (2012). The sense of arrival is an interesting one, and well matched to the concept of chance communication.

Citizens Band (2012) traces unique musical and aural languages that are played in succession – like chapters or movements in a symphony – across time and space: a blind Algerian refugee musician on a Parisian subway; a Cameroonian woman “playing” percussion in a swimming pool; a Mongolian throat singer playing the morin khuur (horse-hair fiddle) on a street corner in Newtown, and a whistling Sudanese-born Brisbane taxi driver riffing on sacred Sufi melodies.

Each performs a musical tradition from their homeland adapted for a new environment, explained Bree Richards, Curator Contemporary Art Practice – Global at the National Gallery of Australia. This work won Mesiti the Anne Landa Award.

‘Citizens Band’ 2012. Excerpt from Angelica Mesiti on Vimeo.

That idea of language carried to an adopted home is a very layered conversation, but in the hands of Mesitit it goes beyond politically toned refugee rhetoric or the hip vernacular of living peripatetically, and becomes about a universal conversation – one that makes our world very small. The underling current to that is one of admiration, and in turn, respect.

We do it too – Talking with our hands

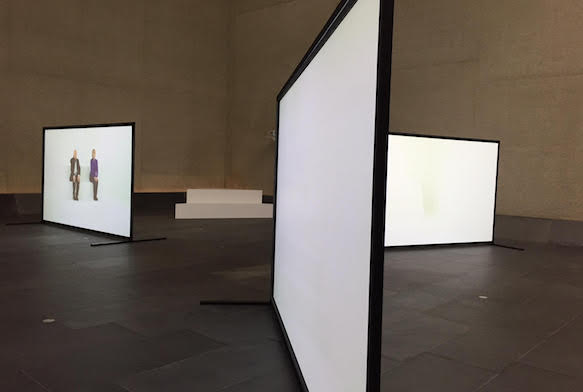

In the final gallery, three double-sided screens hover for the video trilogy The Colour of Saying (2015), which explores more explicitly how the body can be used to communicate.

We are all guilty of the act of “talking with our hands”. Mesiti extends that vernacular by looking at a sign language choir from Sweden, the Önnestad Folk High School choir, alongside two ballet dancers, Rolf Hepp and Jette Nejman, who ‘dance’ a pas de deux using just their hands while listening to Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake on their headphones, and two percussionists who break the silence with loud rhythmic clapping to perform a minimalist piece.

Richards adds: ‘For Mesiti, the body serves as both subject and object, a means with which to mark time and an instrument for creating rhythmic beats.’ The piece is both minimal and immersive as an experience.

Installation view NGA, The Colour of Saying

Overall this is an incredibly elegant show, and when considered together, this suite of video works reveals Mesiti’s amazing capacity to bear witness on humanity. It is silent but intense; it is incredibly intimate and yet familiar and public. It is nostalgic and caught in cultural memory; a soft and gentle lament and yet resilient and contemporary. It offers an answer to now.

When I saw this show to review, a school group was sitting in the space where The Calling was shown. As I moved through the exhibition it was the whistle of those children that replaced Mesiti’s on screen. Non-verbal communication had the capacity to speak to a generation of “digital swipers” – Mesiti’s film more lingering than anything recently seen on their iPhones.

There is no doubt that Angelica Mesiti is an artist of our time who will hold an important place in art history. The work is strong enough to stand without fanfare, special effect, no big splash of colours or bold vibrating sound bleeds, and the NGA has captured that integrity of the work beautifully. Timeless good art.

Angelica Mesiti

National Gallery of Australia, Contemporary Art Galleries

9 September 2017 – March 2018