Stepping off the quieter streets of Boorloo/Perth’s CBD and into Sweet Pea Gallery, I am first confronted by the grating audio of Dan Bourke’s single-channel video essay Attention Economy, a randomly sequenced collection of strange, half-baked – but ultimately trending – TikTok videos.

It evokes the sensations of sitting on the train, across from a stranger tapping through TikTok with their smartphone on full volume. The stranger never fully consumes any of it in its unquantifiable abundance. I don’t know exactly when it is that they will alight, but I’ve committed to the length of this journey.

Holistically, Attention Economy presents a print and sculpture amalgamation of ‘Montessori busy boards’ and digital skeuomorphic design. In their intended context, Montessori busy boards are a tactile sensory activity designed to guide the learning development of babies and toddlers. While skeuomorphic interface design functions to digitally imitate real-life objects (such as a calculator, camera or compass) in order to make digital touchscreen devices easier to navigate.

The internet has always had an expansive capacity to reach some pretty strange and inexplicable places, but with the ever-evolving nature of social media, its strangeness is more readily available than ever before.

Within a society ‘overladen with content’, as Bourke describes, engaging meaningfully with the production of art can feel like an untameable beast.

Dripping in humour and irony, his exhibition Attention Economy posits the reality that an oversaturation of monetised documentation of our lives on the internet collapses boundaries between work and life. As Bourke says in his artist statement, ‘Bathrooms become stages, bedrooms become studios and life becomes content.’

Is it possible to build a profile as an artist without the internet? Are artists at risk of even more unseen, unpaid labour in the pursuit of a sustainable artistic practice? ArtsHub posed these questions to Bourke.

Aisyah Sumito: A ‘Montessori busy board’ is intended to engage a child’s sensory development without overloading their learning process. These objects you have created, and the tech context they are drawn from, stray from this original intent towards somewhere truly ‘busy’. What were your intentions in reappropriating the ‘Montessori busy board’ in the making of Attention Economy?

Dan Bourke: I first encountered Montessori busy boards through a Facebook Marketplace suggestion. I became interested in their specific aesthetic qualities (varying in appearance and quality, depending on whether produced commercially or at home) and use of security hardware (frequently incorporating padlocks, combination locks, door handles and sliding door chains). In combination, [they] read to me like either excessive use of clipart in desktop publishing in the ’90s and ’00s or early UI (user interface) design from the ’00s and ’10s.

At the time, I had been thinking about the contemporary art object as a medium intended to communicate concepts or ideas to its viewers and was wondering about the efficiency of this communication today, following on from the dematerialisation of the art object in the ’60s and ’70s, its subsequent rematerialisation under late capitalism, and Web 2.0’s inversion of the historically typical producer/viewer relationship (in which there are now far more producers of culture and content than there are viewers for it).

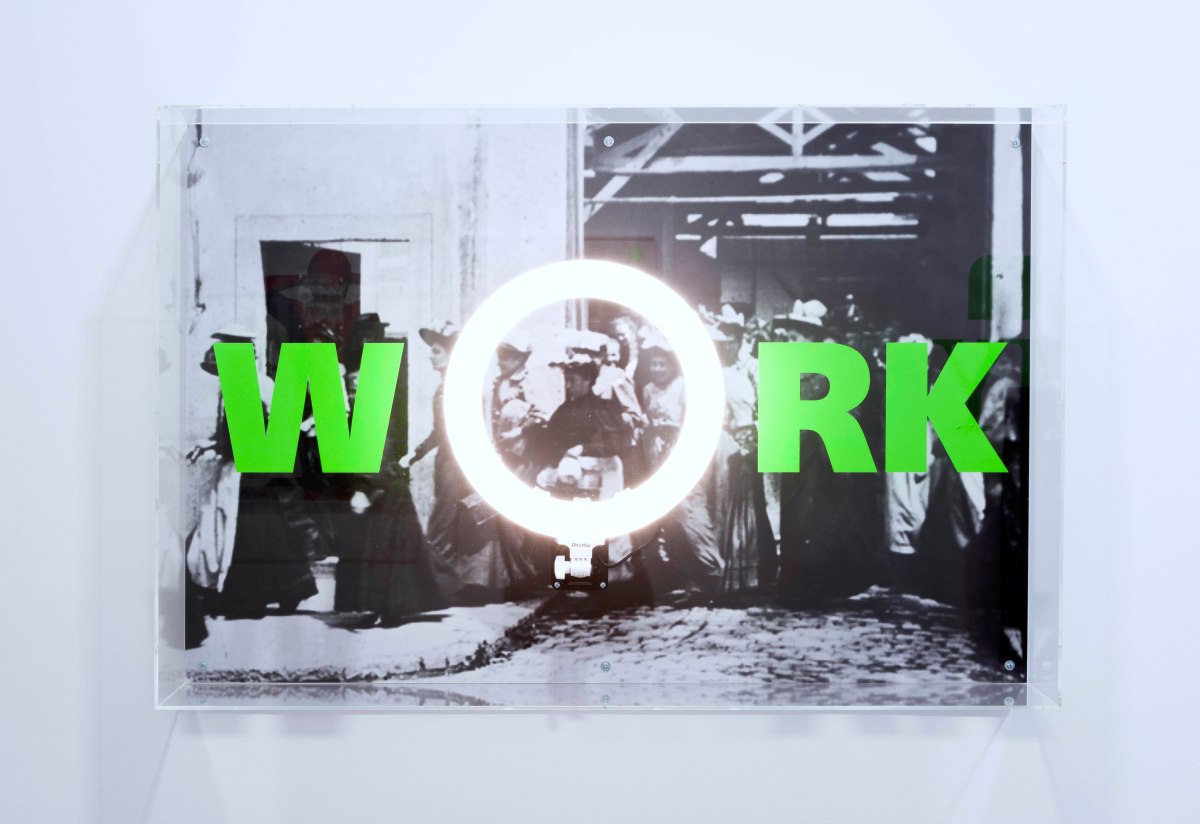

By accessorising the artworks with hardware and fixtures borrowed from Montessori busy boards, and containing them within acrylic box frames, I wanted to maintain the semiotic implications of security, restriction and barriers inherent in these toys, while removing their intended function of tactile engagement and occupation.

The works became a way of working through ideas concerning engagement, transparency, accessibility and the aforementioned efficiency of communication between an art object and its viewer.

AS: Skeuomorphism digitally replicates or emulates analogue tools rendered somewhat obsolete by the everyday smartphone. Attention Economy seems to concern itself with the tension between innovation and obsolescence in technology. How does skeuomorphic design play a role in representing this tension?

DB: While my interest in thinking about skeuomorphic design started with the aesthetics of Montessori busy boards, I’m not sure how readily apparent either of these two references ended up in the final works (with the presence of the security hardware aside).

I’d initially imagined the artworks being more heavily accessorised, but the combination of elements started to read quite differently when juxtaposed with the final selection of images I had appropriated from different media sources.

Concerning these ideas of UI and UX (user experience), I wanted to create a tension between making something that would be aesthetically pleasing and engaging (relying on familiar visuals like commercial vinyl signage, acrylic retail displays, film and TV title sequences and ‘critical graphic design’), but also challenging and overstimulating (with layered content, notoriously difficult RGB (red, green, blue) hues and a randomly generated video essay intended to be difficult to ever be viewed in its entirety).

Read: How social media is changing the way we experience art

AS: The financial and funding precarity of artistic practice necessitates that practitioners must work endlessly to build, and maintain, a visible profile. In the media landscape of social media-based content production, it can be difficult to balance the labour of maintaining visibility as well as the production of art itself. In terms of sustainable artistic practice, what is it about this media landscape that this body of work contends with?

DB: I was especially conscious of that labour when making this work. Not only are we competing with one another within the art world, as has typically been the case with limited opportunities and attention for all arts practitioners, but we are now also competing within a larger world of culture and content, thanks to Web 2.0’s flattening effect and its impact on our attention spans, which necessitates more work than before to participate.

Subject to algorithms and advertising, I feel increasingly fatigued when engaging with culture online. The more I consume, the more tired and disenchanted I become, and the less I feel inclined to produce my own work.

Dan Bourke, artist

With life online impacting life offline to the extent that it does, and participating in the art world requiring some level of taking the offline online, I am unsure how to begin to separate the two.

Making the works for Attention Economy was intended to help think through some of these ideas and question this engagement… Are the conversations intended to be prompted through contemporary art already happening outside of the art objects? In the ‘long tail’ of culture and history, is it still possible to create an artwork that can last beyond the present moment? What happens when an artwork doesn’t work?

Unfortunately, I still have more questions than answers.

Dan Bourke’s Attention Economy is presented at Sweet Pea Gallery in Perth, 10 September until 29 October.

ArtsHub is a publishing partner of the 2022 National Gallery of Australia’s Digital Young Writers Mentorship Program, supported by Learning and Digital Patron, Tim Fairfax AC.