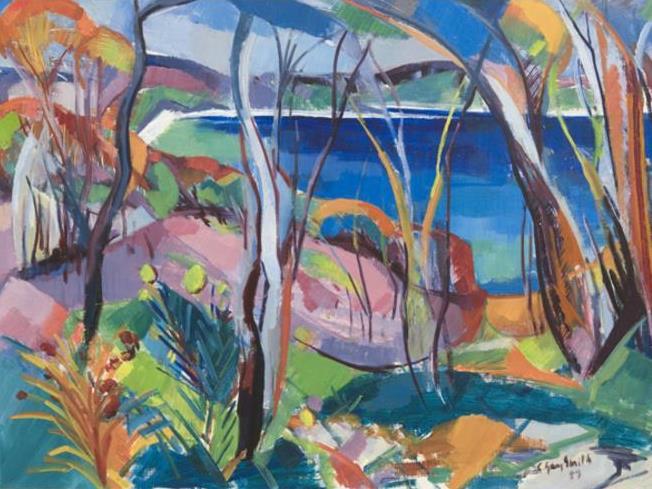

Torbay (1957) is on display at the Art Gallery of Western Australia in the first major retrospective of the neglected artist for 35 years. © Susanna Grey-Smith and Mark Grey-Smith

The recent television series The Art of Australia presented by Edmund Capon, and its counterpart Hannah Gadsby’s OZ, offered a blinkered view of Australian art practice that ended at the 129th meridian east longitude. Capon included just one artist from Western Australia – Rover Thomas – while Gadsby failed to acknowledge any creative activity in the west.

The current exhibition Guy Grey-Smith: Art as Life at the Art Gallery of Western Australia presents abundant evidence of the singular vision of a Western Australian artist and his rigorous reinterpretation of Modernism in response to local conditions. The question that remains is whether it will attract the attention of the Australian art community and national media coverage – or will the tyranny of myopia triumph once again?

Forgetting the west

This conception of the cultural life of Australia isn’t new. There are an embarrassingly large number of books and curated exhibitions produced over the past century that have egregiously used the descriptor “Australian” to describe some aspect of visual arts practice on this continent – but exclude any reference to Western Australian artists, galleries or institutions.

Guy Grey-Smith, Self portrait (1962) Photo: Robert Frith/Art Gallery of Western Australia

Guy Grey-Smith, Self portrait (1962) Photo: Robert Frith/Art Gallery of Western Australia

Retrospectively, curators and critics have often acknowledged they were remiss in omitting artists, events or works held in public collections in Western Australia from their national surveys. Unfortunately, the recorded history is what remains and private apologies do not affect the next generation of critics, curators or art historians who regularly replicate these oversights.

An overlooked artist

Guy Grey-Smith, who died in 1981, was not entirely ignored in his lifetime. But his decision to live in Western Australia his entire life, and to commit himself to local issues and to the task of documenting the unique landscape and ecology of the nation’s western edge, relegated him to a minor league.

Guy Grey-Smith, Quinns Rock (1964) © Susanna Grey-Smith and Mark Grey-Smith. Photo: Victor France/Art Gallery of Western Australia

Other artists of his generation have been accorded monographs and found themselves frequently in the public imagination through exhibitions and television programs. We had to wait until last year for the publication of Guy Grey-Smith: Life Force written by Andrew Gaynor – and it is 35 years since the last major survey exhibition of his work.

Listed in art historian Bernard Smith’s Australian Painting (1962) as one of three artists (along with Robert Juniper and John Lunghi) who were “actively at work today seeking to forge a personal style for themselves relevant to time and place”, Grey-Smith was dismissed four years later by Robert Hughes as “obviously derivative” in The Art of Australia .

Nevertheless that was a great deal better than his total exclusion from subsequent histories such as Christopher Allen’s Art in Australia, Andrew Sayers’ Australian Art, and most recently Sasha Grishin’s Australian Art: A History.

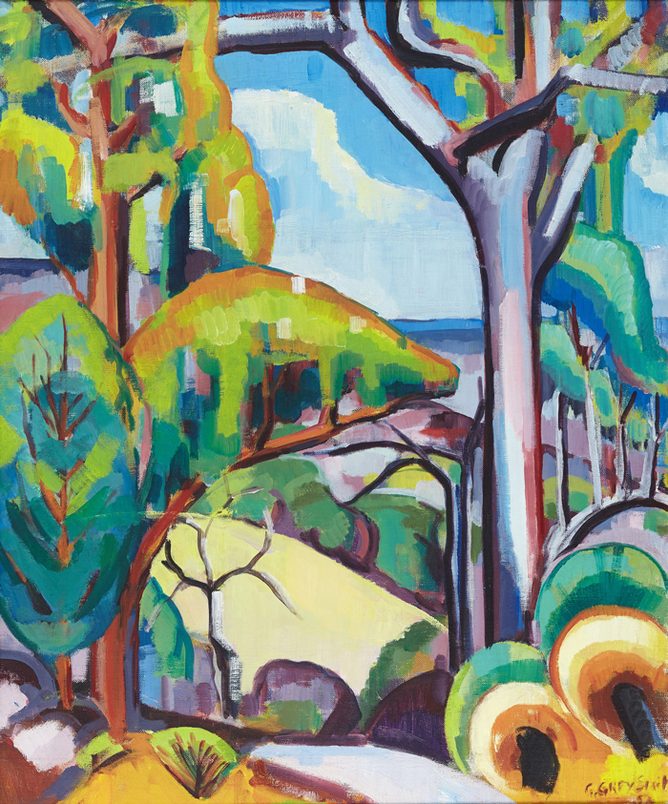

Guy Grey-Smith, Landscape (Hills) (1954). © Susanna Grey-Smith and Mark Grey-Smith. Photo: Robert Frith/Art Gallery of Western Australia

Perhaps it is the “obviously derivative” slur that has marred Grey-Smith’s acceptance into the first league, but like all Australian artists of his generation he was influenced by European, and particularly English, Modernism.

Curator Melissa Harpley charts his development as a painter from his art school obsession with Cézanne and the lessons he learnt during his training under Ceri Richards at Chelsea, to the later thickly encrusted paintings that owed a debt to the Russian painter Nicolas de Staël.

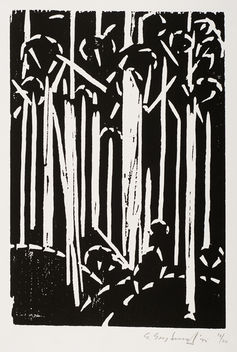

One wall of the exhibition is particularly instructive. We see the artist’s journey from the reductive abstraction of Karri forest painted in 1958 through the agonising trial of merging his knowledge of the landscape with the lessons learnt from Matisse and de Staël.

It is a struggle clearly discernable in the battlefield of Horseshoe Range, worked and reworked from 1958 to 1961, and in the hard-fought success of Sawbacks, Ashburton and Roebourne pass, both from 1961. What this exhibition convincingly demonstrates is that by 1962, Grey-Smith had found a way to combine a vibrant sense of colour with the thick, textural residue of the land to “forge a personal style relevant to time and place” as Bernard Smith proposed back in 1962.

Karri forest II (1975 ). Woodcut on paper. Art Gallery of Western Australia

The Grey-Smiths were a powerful influence on the expanding cultural community of Perth. From their eyrie in Darlington, Guy and his wife Helen worked in a series of studios to create paintings, textiles and ceramics.

The title for his retrospective at the Art Gallery of Western Australia is well chosen because for Guy Grey-Smith art and life were intertwined as an integral unity that provided focus and direction. His unique significance arose from this role as an articulate and imposing spokesperson for the importance of the arts in shaping society.

This exhibition and the recent monograph provide a lens through which to refocus the career of a significant Australian artist.

Guy Grey Smith: Art as Life is on display at the Art Gallery of Western Australia until July 14.

This article first appeared on The Conversation.