The most overused adage when it comes to art prize banter is that ‘You’ve got to be in it to win it’. But is there a science in it? Is it pure luck, or is it true that an elitist cabal of known suspects tip the scales each year?

Regardless of your thoughts, there are few trends worth noting. There has not been a portrait of a politician in the Archibald Prize since 1992, when Bryan Westwood won the prize with an image of Paul Keating in a Zegna suit. Clearly politicians are être démodé.

Increasingly there have been more portrayals of artists; this year 28 of the 51 Archibald finalists are either of artists or artist self-portraits – the largest number to date. And if we are to consider that four out of the eight past Archibald winners have been artist-sitter paintings, it’s a pretty good bet.

This has been emphasised in the hang of this year’s exhibition, where curator Anne Ryan has clustered in the central gallery – the zone colloquially reserved for the winner – artist-subject submissions.

Perhaps Ryan’s suggesting is that all artists are winners, especially those who subscribe to the insanity of the ‘Archibald circus’.

Ryan has flipped expectations from the start with this year’s exhibition. Visitors walk directly in to the Sulman Prize – the smallest of the prizes in both entries and money, and usually tagged on to the end of the exhibition as a postscript.

We are then ushered through the Wynne, eventually entering the Archibald via a circuitous route. These finalists are neatly collated – a gallery for artist portraits, another weighted to the Hyperreal cluster, the last a gentle space for the more intimate portraits.

Does it infer that a small portrait – now tagged on the end – does not have a chance at the big ticket? Natasha Bieniek blew that theory to pieces in 2015 when she won the Wynne Prize with a tiny 9×9 cm Hyperreal painting, throwing perceptions about scale and the landscape genre in a tizz.

What does this all mean? And can past trends and current kudos impact the judges choice? ArtsHub thinks so. And this is why.

Related article: Does being an Archibald finalist help?

Vincent Namatjira Art is our weapon – portrait of Tony Albert (2019), courtesy the artist

Prediction for Archibald

Who: Vincent Namatjira

What: Namatjira’s painting Art is our weapon – portrait of Tony Albert captures fellow Aboriginal artist.

Why: In the 98-year history of the Archibald Prize, it has never been awarded to an Aboriginal artist. This painting screams pure pedigree and box tick. Namatjira is a Western Arrernte man and lives on Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) lands and works at Iwantja Arts.

More interesting to this context, he is the grandson of the great artist Albert Namatjira. He was the subject of William Dargie’s painting in 1956 that won the Archibald.

Vincent Namatjira has garnered a reputation for capturing a wry take on Australia’s colonial history – with recurring references to Captain Cook and the British Royal family – and a satirical unpacking of Australian and global politics. But for his Archibald portrait he turns to an artist who he describes as a ‘warrior’.

Namatjira writes: ‘I wanted to capture Tony’s openness, but also his strength and defiance. The red target on his t-shirt refers to his powerful arts project We can be heroes… I’ve used army surplus camouflage material as the background to represent Tony as a soldier, fighting for Aboriginal Australia – art is his weapon and he uses his practice to highlight Indigenous stories that otherwise remain hidden.’

It captures the spirit of Albert – which helps – but backing up this work is the fact that both artists have enjoyed rapidly escalating careers in recent years with their unique and individual voices. Albert recently had a major solo exhibition at the Queensland Art Gallery and was the first commissioned light projection for the façade of the National Gallery of Australia.

This is Namatjira’s third time in the Archibald Prize. He was Highly Commended last year for his self-portrait, and was also an invited finalist in the UQ Museum National Self Portrait Prize and Art Gallery of South Australia’s Ramsay Prize 2017 and 2019. He has been a finalist in the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Awards five times since 2013, and the John Fries Memorial Award in 2015, 2013.

We suggest it is Namatjira’s time.

ArtsHub Highly Commends: Benjamin Aitken’s portrait of Fiona Lowry, Clara Adolphs’ painting of artists Rosemary Laing and Geoff Kleem (in their garden) – both hung in the central gallery – and love Marc Etherington’s quirky portrait of Idris Murphy and his dog Wally.

The past eight winners have been: Running the numbers one could suggest a 50% chance of winning with a portrait of an artist, and even high when expanding that to the art world circle.

Yvette Coppersmith with Self-portrait, after George Lambert (2018); Mitch with a portrait of artist wife Agatha Gothe-Snape (2017); Louise Hearman with a portrait of Barry [Humphries] (2016) – a first time entrant; Nigel Milsom’s painting Judo house part 6 (the white bird) – a portrait of Milsom’s barrister Charles Waterstreet (2015).

Fiona Lowry with a portrait of architect and art patron Penelope Seidler (2014); Del Kathryn Barton with actor hugo [Weaving] (2013) – her four time in the Archibald Prize and second win after her 2008 with a portrait of herself with her two children. Tim Storrier won with another self-portrait in 2012, The histrionic wayfarer (after Bosch). Storrier won the Sulman Prize in 1968 at age 19 – the youngest artist ever to received the prestigious award – and again in 1984. And it was Ben Quilty in 2011 with a portrait of artist Margaret Olley.

To view the Archibald Prize 2019 finalists

Abdul Abdullah, A terrible burden (2019), courtesy the artist

Prediction for Wynne

Who: Abdul Abdullah

What: A terrible burden, is a large painting (180 x 240.5 cm) that appropriates a colonial-styled image emblazoned with the text ‘a terrible burden’.

Why: Abdullah’s artist statement reads: ‘The history of Australian landscape painting has been cloaked in the language of colonialism: frontiers, exploration and discovery – the language of ownership. The rhetoric regarding taming, conquering and capturing the Australian landscape reflects a desire to possess it.’

Abdullah has described himself as an ‘outsider amongst outsiders’, and his practice is primarily concerned with marginalised minority groups and the experience of young Muslims in the contemporary multicultural Australian context.

‘Frontiers have always been broken’ is a quote from one self-identifying Australian landscape painter referring to the practice of another’ explains Abdullah of his Wynne painting, referring to the 2011 two-man show of John Olsen and Luke Sciberras, described by writer Steve Meacham at the time as a ‘handing of the baton’.

It infers an elitist club that is the Australian art world, adding, ‘Anyway, who says the landscape baton is Olsen’s to pass on?’

Abdullah explained, ‘The phrase written across the painting quotes the latter painter when asked to discuss his status as Australia’s greatest living artist.’

One also might remember it was John Olsen who very publicly criticised 2017 Archibald winner Mitch Cairns’s portrait of artist Agatha Gothe-Snape.

This is perhaps the more astute tone that Abdullah speaks about in his painting – the fraught legacy of Australian art, and the mythology of identity. This criticality and shift in lens is perhaps required for the Wynne.

The last three consecutive years, the Wynne Prize has been awarded to an Aboriginal artist or collective: Yukultji Napangati (2018), Betty Kuntiwa Pumani (2017), and Ken Family Collaborative with their painting Seven Sisters (2016).

It was the first time in the history of the Wynne Prize that an Aboriginal artist was awarded the landscape gong. This year over half of the Wynne Finalists are First Nations artists (15 of 29 finalists).

Prior to this run it was a tiny 9×9 cm Hyperreal painting by Natasha Bieniek that won in 2015. In 2014 it was an expansive abstraction by veteran painter on the scene Michael Johnson that won, and prior to that for two years running, the Wynne was awarded to Imants Tillers for his multi-panel painting titled Namatjira (2013) and Waterfall (after Williams) in 2012 – both paying a nod to artists who have shaped the landscape tradition in Australian art history.

ArtsHub Highly Commends: Blak Douglas collaborative painting with the late Elaine Russell, Ashes, damper and kangaroo stew for dinner. Douglas was given permission to complete the work after her death, which means the resulting work is an interesting cross-generation, cross-cultural synthesis.

To view the Wynne Prize 2019 finalists

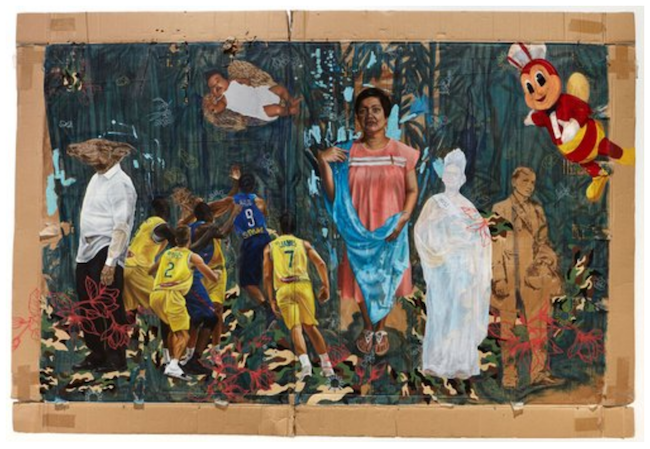

Marikit Santiago, Tagsibol/tagsabong (2019), courtesy the artist

Prediction for Sulman

The Sulman Prize is awarded for the best subject painting, genre painting or mural project by an Australian artist. Each year it is selected by a guest judge. This year it was artist Fiona Lowry, who also happens to the subject of an Archibald portrait this year. She was the winner of the 2014 Archibald Prize with a portrait of Penelope Seidler.

Who: Marikit Santiago

What: Tagsibol/tagsabong, a painting on found cardboard that looks to the past but is very much a satirical commentary on the present.

Why: Tagsibol/tagsabong is an appropriation of Botticelli’s Primavera. Santiago has called on art history’s royalty – Botticelli was favoured by the Medici family patrons – to disrupt the power brokers by telling a multi-cultural story with the veil of authority urshered into the Archi-circle by Botticelli’s authority.

Santiago lives and works in Western Sydney where her practice investigates a personal conflict of cultural plurality at the conjunction of Filipino ethnicity and Australian nationality.

In this work she replaces Venus with her Filipina mother, and cupid is replaced by fast food icon Jolly-Bee (aka Ronald McDonald of the Philippines) again a fabulous pun on where love and manipulation lie.

ArtsHub Highly Commends: Paul Ryan’s painting from a new series Yeah the boys – ‘a rallying cry for young men who maybe feel left behind in a fast-changing world. A world of #MeToo and rapidly changing demographics’.

We also want to pay a nod to Todd Fuller’s animation With whom I was united by every tie (Captain Moonlite), which pays tribute to bushranger Andrew George Scott (aka Captain Moonlite) relationship with James Nesbitt, their same-sex love story unearthed via letters prior to Scott’s hanging.

The past six winners have been: Aboriginal artist Kaylene Whiskey (2018), Joan Ross’ Oh history, you lied to me (2017), an domestic interior by Esther Stewart (2016), Jason Phu’s ink on paper which looked at his Chinese heritage (2015), Andrew Sullivan’s quirky Hyperreal fantasy T-rex (tyrant lizard king) (2014), and Victoria Reichelt image of a deer in a library After (books) (2013).

To view the Sulman Prize 2019 finalists

The winners of the Archibald, Wynne and Sulman Prizes 2019 will be announced on Friday 10 May.

Archibald, Wynne, Sulman Prizes 2019

Art Gallery of New South Wales

11 May – 8 September 2019