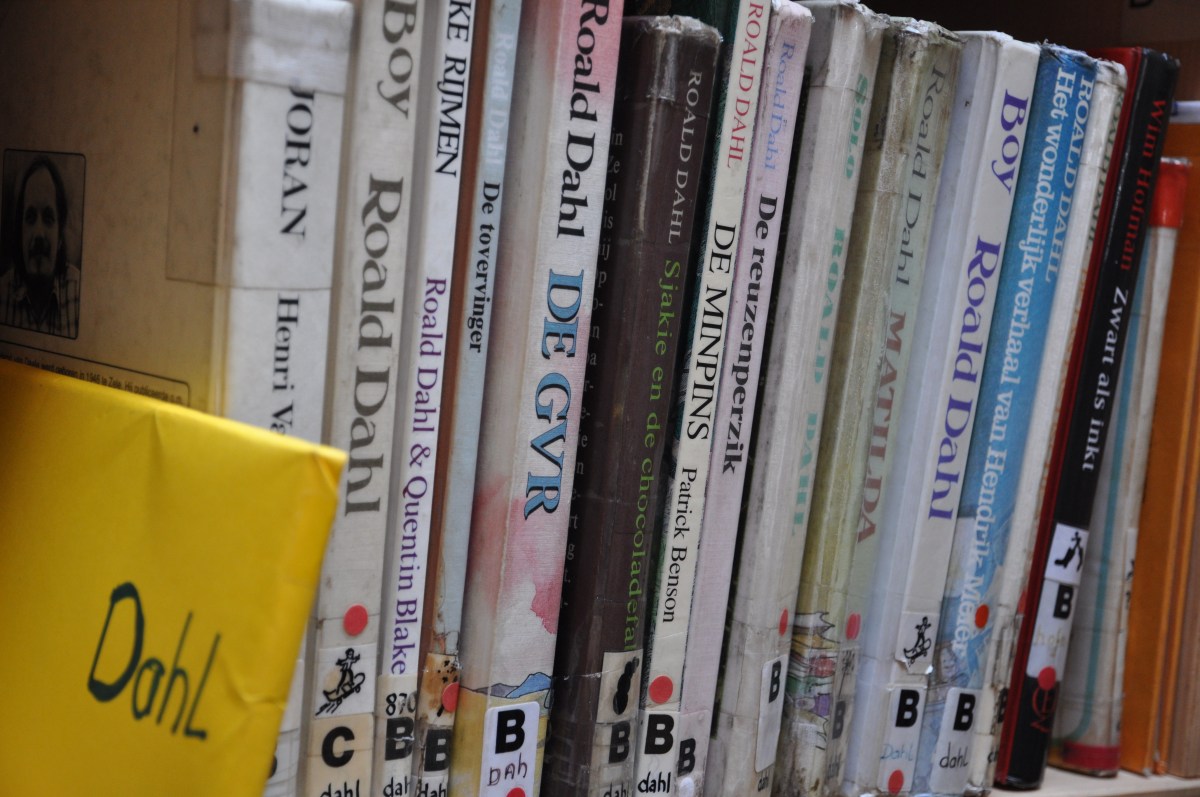

With the announcement that the children’s books of Roald Dahl are being rewritten to remove language deemed offensive by the publisher Puffin, there has been a line drawn between those who believe this is political correctness gone wrong, and those who believe that all literature should reflect the values of the world in which we live.

Lianne Kolirin, for CNN, reported that, ‘In a lengthy report published on Saturday, British newspaper The Daily Telegraph revealed that it had found hundreds of changes across the author’s many children’s books. Close analysis by its journalists revealed that language relating to gender, race, weight, mental health and violence had been cut or rewritten. This included removing words such as “fat” and “ugly,” as well as descriptions using the colours black and white.’

While Hayden Vernon in The Guardian states, ‘Gender-neutral terms have been added in places – where Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’s Oompa Loompas were “small men”, they are now “small people”. The Cloud-Men in James and the Giant Peach have become Cloud-People.’

As an author I don’t believe in censorship or in sanitising literature to make it palatable for gatekeepers; as a teacher, however, I am conflicted. The term virtue signalling has gained a negative connotation, but as teachers we signal which virtues and values are desirable, we model behaviour and we teach ethics to our students.

Teaching primary school students and telling them not to call each other ugly and fat as this is hurtful, and then reading Roald Dahl books with those terms, creates quite a dichotomy. Others believe that texts should remain as they were originally written and in the author’s words, and instead historical context should be provided through a note to the reader, and taught alongside the text.

To get to the heart of this issue I thought I’d get other perspectives from those who are invested in children’s literacy.

Oliver Phommovanh, former primary school teacher, stand-up comedian and children’s writer of What about Thao and other books, believes that the descriptions of characters’ physical appearances should remain as written by Dahl. ‘Back when I was a teacher, I know the challenge of teaching descriptive words to enhance my students writing. If we were to limit ourselves to describing characters that were deemed sensitive, we would have sanitised texts that would not reflect what kids think or say to each other in the playground. I understand that and if anyone is hurt by them, then it’s an opportunity to learn from the experience.’

Megan Daley, author, teacher librarian, creator of the popular website Children’s Books Daily and co-host of the Your Kid’s Next Read podcast, has a different perspective and says, ‘We are fortunate to live in a time where we know better and can do better, and words that describe anyone’s physical appearance in a manner that is ableist or derogatory have no place in contemporary children’s literature.

‘Publishers and authors alike have a responsibility to ensure that language is reflective of the diverse world in which we live in order that we do not create an unconscious bias associating physical appearance with moral superiority – as in cases where villains are described as fat, ugly or missing limbs and the hero is tall, thin and white.’

Phommovanh notes that the Dahl books reflect a certain historical context and by editing the language to suit the times we are losing the opportunity to teach about certain words. ‘I believe a sensitivity note is a good compromise, to set the context of the piece. These texts were written at a certain time and, while we may not agree on some of the language terms or use them anymore, we have to recognise the history surrounding the use of these words.’

Daley agrees that, ‘As a librarian and as an author myself, I do not like to see texts altered or classics abridged. They are reflections of the time in which they were written and to alter language we now know to be problematic is to claim that problems around language never existed. Rather than substantially change a work, I would prefer to see a note from publishers stating that the work is presented as it was written and is a product of its time. That the language and views are not reflective of the publisher or wider contemporary society. Not a failproof solution, but a conversation starter.’

Suzanne Nossel, CEO of PEN America, a network of writers protecting freedom of expression, wrote a series of tweets about these changes: ‘The problem with taking licence to re-edit classic works is that there is no limiting principle. You start out wanting to replace a word here and a word there, and end up inserting entirely new ideas (as has been done to Dahl’s work).’

Another tweet stated that, ‘If we start down the path of trying to correct for perceived slights instead of allowing readers to receive and react to books as written, we risk distorting the work of great authors and clouding the essential lens that literature offers on society.’

Phommovanh agrees, ‘We have to respect the authenticity of the author’s original voice. We can analyse and/or criticise these texts and authors, which can lead to great compelling discussions, but changing words and distorting the author’s voice will only serve to dilute the story, and the story will lose its sense of time as a historical text.’

Daley notes, ‘Publishers and editors often edit future editions of works, usually to amend typos or update information – with the author’s involvement. Many authors will reflect upon their writing and choose to update language or information in future editions. In cases where the author has died, changes need to be made with caution as permission cannot be sought.

‘Again, as a librarian, I do not like to see texts altered without permission from the author.’

As a high school teacher now, I continue this conversation with my daughter and my students, identifying gender-biased language where only male pronouns are used and using this as an opportunity to talk about women’s rights. Or when derogatory words are spoken by hateful characters to portray the reality of prejudice, I speak to them about the way that human rights have evolved, for example, with same sex marriage introduced to create equality or laws against discrimination based on religion.

Phommovanh adds, ‘[I write] funny stories and have always looked up to Dahl in how brazen he is with his wit and sharp observations that poke fun at everything. Comedy is about pushing the boundaries and for a punchline/joke to land, it needs to land on someone or something. You can’t have inoffensive comedy.’

While Daley finds that, ‘As a parent, I have never enjoyed Dahl’s writing and find much of his language personally offensive. I have chosen not to read most of Dahl’s books with my own children and when we have read a few of his books, or seen screen or stage versions of his work, there has been discussion around this. Of course, not all adult readers of kids’ books will know a book as well as a parent who works in the book industry, as I do.’

As the child of migrant parents I missed out on a lot of the cultural capital that my peers received and so I bought the entire collection of Dr Seuss books while I was still pregnant, and waited a couple of years before I could read them to my daughter at night. I remember her eyes sparkling wth delight at the playful rhymes and the humour. As she got older and asked questions about language, I took the teaching opportunity to engage in the texts.

Phommovanh signals a warning call about the future of children’s literature if we keep going down this path – ‘If contemporary writers such as David Walliams will cop the same treatment when stories like The World’s Worst Teachers or Gangsta Granny are deemed offensive in 20 or 30 years’ time? Will ‘Wimpy’ be too harsh, and we’ll end up with Diary of an All Right Kid down the track?’

And where does this end? ‘If we keep censoring descriptive words for human characters, then authors will simply use animals; hence, the talking animal phenomenon in picture books and children books. But then will people get offended if we describe dogs as ugly or pandas as fat?’

Read: What’s happening to art censorship in the age of cancel culture?

If we sanitise these historical texts, we lose these learning opportunities and create a darker future for our children. We can see this being played out with the Australian curriculum being updated so that Holocaust studies are compulsory for middle years, as there has been the loss of knowledge about genocide and prejudice, and the rising voice of the alt-right in the US and bleeding into the rest of the world. Let readers make their own choices about what they choose to consume or not.

To learn more about Oliver Phommovanh and his books.

To learn more about Megan Daley and her work.

To visit the author’s independent press, Pishukin Press.