It’s a privilege to be speaking to you all today on the traditional lands of the Eastern Kulin nation. I’m trying to get better at acknowledgement of place by doing a bit of research before I get there. It’s my understanding that the name of this place, Prahran, is actually a corruption of the name, Pur-a-ran. I’m told it means land partially surrounded by water and that it was an important place for ceremony.

Being in this building with you all, I’d also like to acknowledge that there are lots of challenging things happening out there, locally and globally and that we should begin this summit by clocking the privilege that is this group of people getting our heads together to make the world a more pleasant place to be through the facilitation of unifying cultural experiences for audiences and nourishing, meaningful, employment for arts workers into the future, a task that can seem rather insignificant when we tune in to the news at the moment.

So…

Ladies and gentlemen, distinguished guests, and circus enthusiasts, welcome to ‘The Moving State of Circus’. Today, we come together beneath the grand circus tent to embark on an inspirational journey.

We’re here to celebrate the remarkable transformation of the Australian circus industry, where creativity and determination have fused into a magnificent display of human potential. From humble beginnings to the grandest of stages, circus has always epitomised the spirit of pushing boundaries and defying gravity. As we look to the future, let us be inspired by the innovation, resilience and sheer audacity of those who have turned dreams into awe-inspiring reality. In this world of movement and magic, we find our inspiration and our limitless potential.

***

I’ll pause there to confess that the awful introduction that I just read for you was actually generated by an artificial intelligence Chatbot – ChatGPT. The prompt I gave it was: ‘Generate an inspirational, 100-word introduction to a keynote address aimed at the Australian circus and wider arts industry, titled The Moving State of Circus’.

Like the Chatbot, the world and the people in this room are well aware of the ways that circus, at home and abroad, continues to gain popularity and legitimacy as an art form – not to mention its meteoric rise as an important national export, culturally and economically.

Of course it’s impossible to talk up the triumphs of the sector without some acknowledgment of the hardships dealt during the last few years and the challenges that have appeared on the horizon:

- a destabilised situation for Victoria-based circus practitioners at student and professional levels

- a decimated local and international arts workforce and other symptoms of industry ‘Long COVID’

- the worsening state of mental health for arts workers at every level of the industry

- global conflict and the prohibitive costs of making or touring work, and

- the degradation of the environment and the outdated systems we use to present that work globally.

It’s not all roses, to say the least.

My guess is that the many minds in this room know a lot more about these challenges than I do and I’d be a fool to claim any better. As my father (a mechanist at the Victorian Arts Centre and Victorian Opera for many years) would say, ‘What would a warm prop with a speaking part know anyway?’

But the truth of the matter is that the future of this industry does depend on us and our ability keep the state of circus moving forward, albeit, into an increasingly uncertain future.

Read: Can Australian circus bounce back from pandemic disruption?

So instead of commenting on things that I can only claim to understand the surface of, I’d feel more comfortable sharing with you some thoughts and observations I’ve made over the last 35 years that I think have helped the state of circus move toward the privileged position it occupies in this country and on the world stage right now, as told through a couple stories that I feel best reflect this.

When I said that I’d feel more comfortable, the truth is that I’ve found nothing comfortable at all about preparing for this keynote. After accepting the invitation to speak I was immediately engulfed by the familiar feelings that I was out of my depth. That I didn’t have anything important to say to you all and that I was an imposter.

I’ve come to understand that this is just part of “my process”. It’s the same feeling I battled when I was a student, performer and still now as I’m directing work or speaking with anyone whose status and reputation impress me like many of the people in this room.

Can I please get a quick show of hands from anyone here who has ever felt something similar? Look around – it appears, we are not alone…

So after a brief battle with my familiar demons I asked myself the question: what do I have to offer this audience?

Three short stories, all true, from early, mid and current stages of life that I continue to think about and learn from and will hopefully add some value to this summit and keep the state of circus moving.

Story one: On the importance of double forward flips

About 35 years ago I was on the bank of the Barron River in remote Far North Queensland (FNQ) at a place called Mantaka with my friends and family. A game had started. If the game had a name it would be, ‘Jump off the steep sandy river bank into the water – with style.’

It was one of those infectious games that would have no end unless our parents dragged us home or the light got so low that we would start to place doubts in each other’s minds about the presence of crocodiles in the river.

The game, as I remember it, was as much about the spectators and their reactions as it was the stylish jumps.

The stakes in the game started to climb as spins, then flips, became introduced and that was the moment that arrested my attention. Suddenly I was no longer playing. I was watching and totally invested in the failure as much as the success of each leap.

Without me realising, one of my friends had left the game and gone home and returned, carrying an empty three-litre cordial bottle. The kid’s name was Carl Brim or Lefty, and he was known as one of the clever kids that could fix stuff when needed – mostly, trampolines, bikes and slingshots.

I noticed that the bottle had been modified. The lid had been taped on with some kind of heavy duty tape, and as he took the bottle to the Launchpad, he dug a hole in the sand and located it right at the precipice.

With almost no hesitation, Lefty – after a small test of the bottle’s pneumatic pressure – walked back, ran at it and sprang off, managing a double forward flip into the river.

And the crowd went wild. I was inspired.

Judging by how often I revisit the memory of that afternoon, I think my ongoing love of human physicality was seeded that day and in many ways it is embodied by the physical gifts of First Nations Australia. I grew up in a mixed-race household in FNQ with a half-brother whose father was a proud Dingaal Warra man from Hopevale on Cape York Peninsula.

Rory, my brother, was a sporting star and five years older than me. It seemed like every other week, he was winning a best and fairest trophy or going on state representative coaching clinics for cricket, soccer, AFL, rugby league or anything else he put his mind and physical talent to.

He could juggle and do backflips as well.

To say that he was gifted is an understatement. He was a constant source of inspiration, and I aspired to being just like him.

But I was different to my brother and Lefty. When Lefty was doing the double forward somersault into the river or my brother was facing the elite pressure of competitive sport, I was mentally projecting the image of my failure where I broke myself in the attempt. Despite this obvious difference, the fact that I could see that it was possible gave me enough courage to at least entertain the idea that with the right steps I might be able to do it too…

In my colloquial and unresearched opinion, you have two very different types of person and subsequent learning styles when it comes to learning acrobatics and any physical skills that have an element of danger. I categorise these as the “Chuckers” and the “Contemplators”.

Chuckers know a physical skill is possible and can visually download the basic principles to attempt it. You see them at skate parks or on trampolines at six years old with the confidence and bravery necessary to excel in what can be fear-inducing situations.

They pick things up really fast because the act of watching another body turns into a feeling for how to do it inside their own.

Contemplators, on the other hand, need time, explanation and strategies to overcome their fears and the dangerous baulk reflexes that come with them. They rely on careful development of the necessary checks, balances and progressions, and can suffer big setbacks in confidence when things go wrong.

My personal experience says that both the Chuckers and the Contemplators can reach the pinnacle of skill development and will undoubtedly need different tools and strategies to get there.

Naturally, they will reach different milestones at different times, but the one thing they both need to reach that pinnacle is each other.

The Contemplator needs to see the bold courage of the Chucker and the Chucker will hit a plateau of development without adopting some of the Contemplator’s approach and ultimately lose interest without the exciting possibility of future success.

I’m acutely aware of how reductive I am being, but what I’m trying to get at is that inspiration, courage and a measured approach continue to be the most powerful combination of factors when setting out to accomplish something that I have encountered, and that this extends far and beyond the acquisition of physical skills.

To quote a dear friend of mine, Joshua Hoare, a great Australian circus thinker who graduated from this very institution: ‘Circus shows us the simple binary between success and failure as humans.’

Story two: Base-splaining and the Rudi Mineur Method

It could be said that circus artists have a kind of reverse career trajectory when compared with other art forms. When a circus artist is at their physical peak, they are often at the beginning of their artistic development. Unlike a painter or a singer whose technical ability often grows alongside their creative practice, perhaps reaching the peak of their artistry in their 60s or 80s, a circus artist is often expected to realise their best work between the ages of 20 and 30.

In 2004 I joined the Rock’n’Roll Circus ensemble in Brisbane. The company had a fierce reputation for innovation through the late 80s and 90s and when I arrived I was the ripe old age of 19.

I’d completed years of training, first at community level at the Blackrobats in Kuranda, FNQ with community circus legend Kelly Craig, and then for seven years at the Flying Fruit Fly Circus under master trainer and living legend Mr Lu Gong Ruong (a man I’d like to acknowledge as I stand inside this institution) and the Artistic Director, the formidable Kim Walker.

I’d landed the job after a stint as the work experience kid and was inspired by the research that Yaron Lifschitz, my long-time friend and collaborator was doing. It was different to everything I’d seen before and I was keen and eager to make an impact.

With almost a decade of serious training behind me, I thought I knew a lot of stuff. Saying it differently, I was entering my physical peak, and knew very little about most things associated with being an adult.

There was a particular style of circus communication that was common 20 years ago that I’m glad to say has lost popularity.

For the purpose of this story I’m going to call it “base-splaining”. For those of you who need a bit more context, we reductively categorise acrobats into one of three different groups. Base on the bottom, middle in the middle and a flyer on the top.

Put simply, base-splaining is a style of communication where the base is always right.

So there I was, 19, with something to prove and the biggest acrobat in the company, complete with my base-splaining toolkit when thankfully I met a great artist by the name of Rudi Mineur.

Rudi, in my opinion is one of the most important characters in the story of Australian circus over last 30 years with his physical and conceptual contributions continuing to ripple into the very fabric of the industry today.

Somewhere during my first year at Rock’n’Roll Circus (soon to become Circa) we hired Rudi to come and do some skills training with us and I was immediately struck by how easily he worked with people and how quickly he seemed to be able produce difficult acrobatic results and a deep level of trust. Yes, he was older and more skilled than I was, but he never claimed to know better than anyone in the room and there was not a hint of base-splaining in his method.

It became clear to me that instead of focusing on what his acrobatic partner or team was doing wrong or could do better, he used four simple words to ask a question that seemed to not only remove developmental roadblocks, but also made the transaction feel less tense and more connected: ‘What do you need?’

This is how it works for an acrobat.

If a flyer falls off the top of a pyramid enough times they develop fear. The fear would then make the flyer more likely to fall off again because they were thinking more about what was going to happen if they hit the floor than the necessary steps needed to do the skill safely. No amount of base-splaining the necessary steps to the flyer after each failed attempt addressed the bigger cause of ultimate failure, the fear.

In Rudi’s approach, the moment fear crept in to the equation the magic words were applied. ‘What do you need?’

The flyer might reply:

- to feel less slippery

- to know what happens if I fall off

- I feel too close to that wall

- to do it many more times with more safety equipment so that I can focus on the steps, or

- the public performances are approaching too quickly and I’m worried that we are rushing it.

All of the needs were profoundly simple things to address and, what’s more, it usually caused the same question to be asked to the base or middle in return.

Never have four words been as useful to me than these and not only on the training floor.

The words have been invaluable in practically every interaction I’ve had where I care about the outcome – whether I’m interacting with artists, presenters and agents or my children, my partner or my community.

Base-splaining is just another term used to describe speaking with authority before you understand someone else’s perspective and it’s not just 19-year-old me that is guilty of doing that from time to time. The more turbulent and dynamic the situation the more frequently the question can be asked.

It’s been my experience working inside teams of people that, when things get stressful, the perceived stakes are high, and the deadline is tight and/or there are not enough resources to go around – like, say, in the Australian arts industry – it’s easy to fall into the trap of being critical first and proactive second.

Rudi Mineur’s method and those four simple words, ‘What do you need?’ transformed my approach to circus and life itself. As I continued to work with Rudi and learned from his gentle yet impactful guidance, I started to witness profound changes in our ensemble.

The elimination of base-splaining (most of the time) allowed a new level of collaboration to flourish.

Instead of the base claiming they knew best, a better style of open dialogue and respect among the acrobatic team took root. This shift in communication fostered a sense of trust and unity that transcended the training room. It was no longer about someone being right or wrong, but about understanding each other’s needs and getting excited about solving the problem in front of them that was, now, tangible.

On reflection, it wasn’t just a great communication tool I was exposed to, but what I believe to be great leadership.

During the next 12 years that I spent at Circa, followed by the seven at Gravity and Other Myths, this method has revealed yet more to me: that sometimes collaboration should takes precedence over hierarchy.

It recognises that in various creative endeavours, experienced individuals often presume they know best. There is a time and place to remove hierarchical thinking in favour of collaboration or bold new directions.

If effective communication stands at the core of any successful creative project, then it’s my firm belief that the simple question, ‘What do you need?’ can unlock constructive dialogues and enhance interactions between artists, presenters, funding bodies and philanthropy. A willingness to listen and adapt can lead to more rewarding collaborations for all involved.

Rudi’s humility, marked by a commitment to never claiming to know better than anyone in the room, emphasises lifelong learning.

In the arts industry, and I imagine any industry, remaining open to new ideas and perspectives will foster ongoing growth and innovation.

Whether you’re a young emerging artist or a seasoned professional, the question, ‘What do you need?’ always offers the potential to shed new light on the challenges before you.

Story three: The show that would never tour

In January 2020, Gravity and Other Myths had all three of its ensembles touring far-flung regions of the world. A month later we had all 34 staff grounded in Australia. Stripped of our most precious commodity as physical artists, human touch, our disorientation was, like everyone’s, very real.

The silver lining of course is that, as a company that doesn’t receive ongoing multi-year funding, we essentially ended up as a funded company for the first time ever, in the form of JobKeeper.

From this space of utter disorientation we began an optimistic 14-week process of project development codenamed, ‘There’s no I in Quaranteam’ – 42 creative tasks digitally distributed, returned and distilled into potent departure points for creating new and various kinds of work. We pivoted, waltzed and step-ball-changed toward new formats and outputs that didn’t involve the bread and butter of international touring that the company was built on, in an attempt to find new ways to pay the bills and feed the mouths of our people for when the support tap was inevitably turned off.

Film projects, educational resources, virtual training floors. It was demanding, exhausting, exhilarating and the most galvanising moment in our company’s time together.

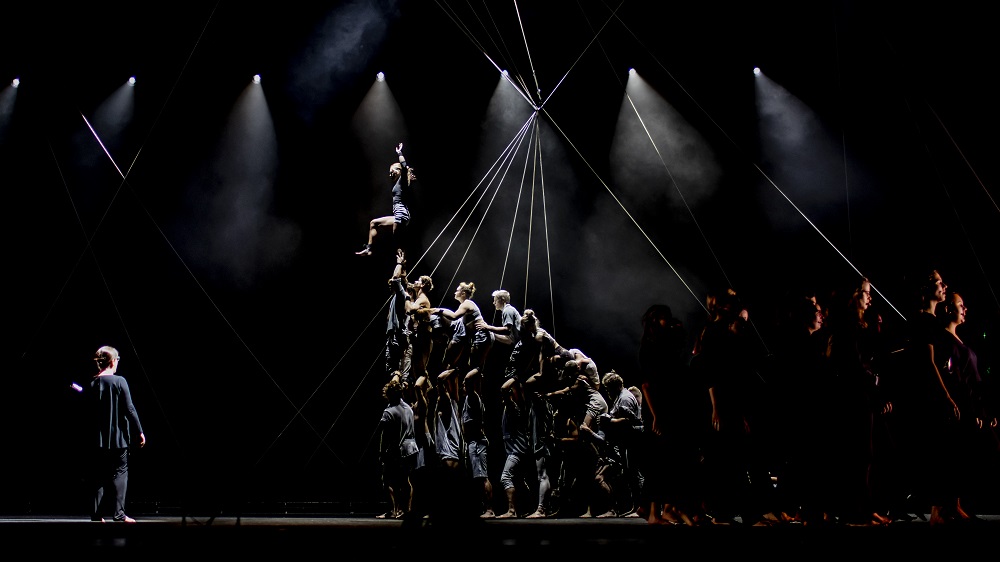

Among the suite of projects – and, dare I say, products – that we undertook the creation of was to realise the dream of combining all of our ensembles and working with the same number again in the form of a vocal ensemble to create a work that would become The Pulse – a kind of COVID-response piece.

It struck me during the pandemic that most things can be described as waves and cycles. Life, time, light, matter and human history can all be described as endless waves of growth and decay and I think it was this lens of catastrophe that made us zoom out and consider our place in the scheme of these bigger cycles. Up and down. On and off. Try, fail. Boom, bust. Wake, sleep.

I believe circus is an ideal medium to demonstrate the potential of the collective and we used this opportunity to test our own potential as a company to see if we could fill the vacuum in our major festivals left by the absence of big international imports, while also demonstrating resilience and adaptability in the face of uncertainty.

With lots of work and even more good luck and a list of contributors and champions too long to mention The Pulse toured to three major Australian arts festivals. We were ecstatic, but … the size of the piece with over 60 artists on stage would make it prohibitive to tour internationally – wouldn’t it?

Every historical example would say so.

I’ve discovered a simple formula that you can use to determine the true selling price of a touring show, no matter what the size and scale. If what you need to tour the show is X then the world is always willing to offer you 30% less than that (that was a joke).

Whether it’s a popular idea or not we all measure the cost of making and touring work before it is made.

We did not build The Pulse as a work to tour and honestly did very little to consider these costs with regard to international touring, but following our seasons in Australia we were offered a run in the Edinburgh International Festival (by my friend and colleague Fergus Linehan) that was supported by the South Australian State Government and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade as part of the UK/Australia season. Right place, Right time.

This isn’t a self-congratulatory story to demonstrate mine or Gravity and Other Myths’ broader expertise in bringing big ideas to life. While I’m proud of our team and the perceived mountains we moved, the truth is that the mountains moved themselves.

The Pulse wasn’t built to travel internationally and yet just a month ago we finished a world tour of the piece with a party of 70 staff (including the phenomenal Cor de Noies from the legendary Palau de la Musica in Barcelona) to four countries across two continents and met over 24,000 audience members over a six-week period – and there is a very real chance that this will happen again during next year’s northern summer festival season.

When I reflect on the various series of improbable events that led to this beast touring, I’m left with this summary. Warning, it’s dense.

The show that was never built to tour is touring because artists, impassioned by a big idea, met fearless presenters, through ambitious agents, and secured concrete invitations and, despite the economic reality of no festivals being able to afford such a tour, peak funding bodies at state and federal level combined forces with private philanthropy to cover the gap and get the tour across the line.

And with that, 70 people from two cultures and an untold number of champions from festivals, venues, various offices, departments, generous individuals and ticket buyers around the world, demonstrated the real power of the collective, a collective that moved mountains and in the process gave each other real hope.

Conclusion

In both traditional and contemporary contexts, circus captivates us, whether as riverbank expression session, frivolous escapism or as a medium for experiencing existential awe.

‘The Moving State of Circus’ resonates with our aspirations and reminds us of our potential.

Over the next two days, we have the privilege of listening to a multitude of skilled and knowledgeable speakers addressing pertinent topics that will undoubtedly shape our future as we ask each other, ‘what do you need?’ and listen carefully to the answer.

Lastly, if I had written the introduction instead of letting ChatGPT do it, it probably would have sounded more like this:

Ladies and gentlemen, or should I say friends and colleagues, people I will ask favours from in the future, people I can do favours for in the future, mentors, teachers and strangers. I look forward to meeting you over the next two days, so that we can begin to understand each other’s needs better and navigate this mixed up world by being more informed and more connected.

Thank you.

This article was presented as the opening keynote speech at NICA’s Australian Circus Summit on Thursday 19 October 2023. The summit was held on the unceded lands of the Kulin Nation.