Tasmania’s convict history has always fascinated me. At Port Arthur, I’ve felt the uncanny juxtaposition of beauty and tragedy that hangs in the air. Visiting the Cascades Female Factory in Hobart, I’ve touched the rough sandstone wall surrounding that brutal place where women scrubbed laundry in the bitter cold for up to 12 hours a day.

My family stayed at a former convict outstation turned into accommodation when my children were young, and we told them censored tales about the convicts who were flogged and housed in dank, overcrowded cells. We even braved the Port Arthur ghost tour in the inky darkness – twice.

I’ve visited the cells at Richmond Gaol and seen slashes carved into stone that mark off weeks, months, years of a prisoner’s existence. I have even shut myself into a suffocating solitary cell to experience the terror of sensory deprivation. Convicts were something I knew a lot about – or so I thought.

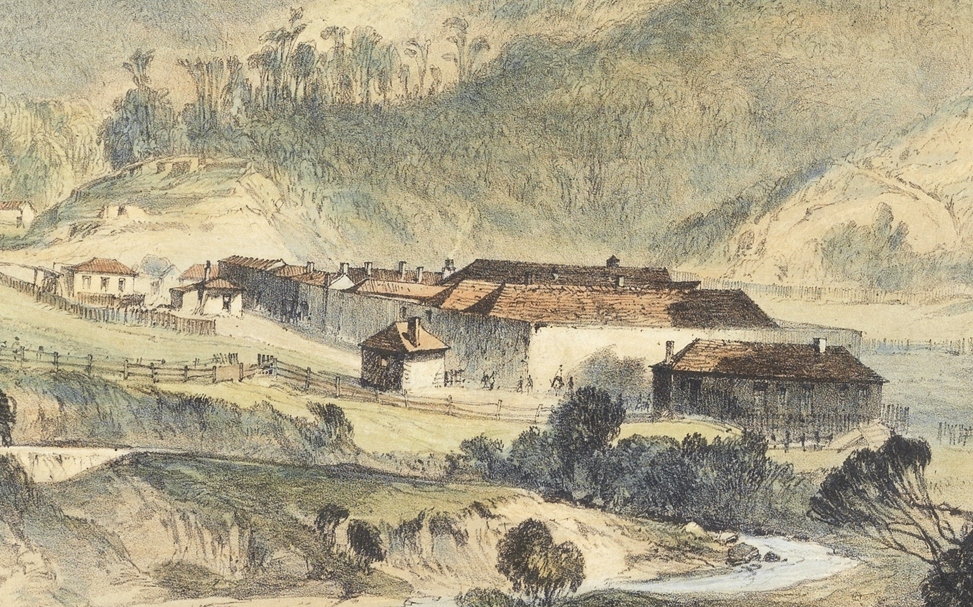

So when I began writing Blackwater, a Gothic psychological thriller set in the current day, it was a natural choice to create a fictional convict outstation for women. According to The Female Convicts Research Centre, 13,500 women were transported to Tasmania as punishment for their crimes between 1803 and 1853, and I wanted to explore what life was like for them.

Writing is a strange, serendipitous process. Once an idea is set loose, things click together in mysterious ways. Sometimes a character comes fully formed, like my protagonist, Grace, who arrived on the page seven months pregnant. But I didn’t know why, and it took several drafts of the novel to work it out.

Once I’d decided my setting was a former convict outstation, my research began. But something was missing; there was scant information about what happened to the babies of convict women.

The Female Convict Research Centre has a website dedicated to these incarcerated women. Unlike the vast amount of information readily available about Port Arthur and male convicts, this website is one of only a few resources that contain detailed information about the infants of these women.

It was here that I discovered the bleak history of convict nurseries. Getting pregnant while incarcerated was common, particularly as some women were sent out to homes as servants. And if a convict woman became pregnant, she was immediately sent back to the female factory.

These babies were born into a terrible fate. Many of them died from diarrhoea, malnutrition and other preventable causes. The records are confronting to read: hundreds of infants dead before they reached two years of age, their mothers unable to see them, even though they were housed in the same institution.

Read: Why Australian crime writers are killing it

Professor of Demography, Dr Rebecca Kippen, notes that once babies were weaned their mothers went back to work and the babies were sent to the convict nurseries. At three years of age, the children were transferred to an ‘orphan school’. Ironic, given they were not actually orphans. According to the Female Convicts Research Centre, 1148 infants died in these nurseries between 1829 and 1856, although it’s suspected that many deaths were not registered and the number may be much higher. There were rumours that the bodies of infants were secretly taken out of the factory and buried without record to avoid inquests. If there was an inquest, the cause of death was often inconclusive and listed as ‘a visitation by God.’

Kippen writes that the Cascades Female Factory at Hobart was especially notorious for infant deaths. In 1829, The Colonial Times reported that ‘a great many deaths constantly occur … so many as six or seven children have laid dead there at the same time’. Even though these were babies of convicts, 19th century Tasmanian society was outraged to discover just how dire the conditions were at the nurseries, and the number of deaths. There were several court cases, but conditions for these women and their infants never changed significantly.

Read: Book review: Blackwater by Jacqueline Ross

With the exception of the work done by Kippen and the Female Convict Research Centre, there just isn’t that much written about this, at least not for an amateur researcher like me to find. These babies, who never had a chance at life, have largely been an overlooked part of our convict history.

So, I tried to imagine what life might have been like for those incarcerated mums, cold creeping up their legs as they rinsed sheets in icy water, their babies crying and neglected in a nursery upstairs. Knowing their bedding was flea-ridden and sopping with urine, no fresh air or nutritious food, and only one harried nurse to care for dozens of babies. And suddenly I knew why my character, Grace, was pregnant. My setting, Blackwater, was a convict nursery, and I would tell this story the only way I know how – through fiction.

Blackwater is out now through Affirm Press.