Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse is receiving all the raves in cinemas but, apart from the eye-dazzling animation, what took me by pleasant surprise are the number of contemporary art references packed into that first major fight scene.

As Spider-Woman Gwen Stacy of Earth-65 and the da Vinci-era Vulture battle it out in New York’s Guggenheim Museum, their conversation cleverly navigates the trenches of how art has evolved (or back-pedalled).

If it were possible to count the number of contemporary art pieces destroyed in that scene, the monetary value would be in the hundreds of millions.

Here is how Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse pokes fun at contemporary art, and why it’s funny but also deeply troubling (minimal spoiler alert).

How did a cardboard-dressed Vulture get inside a museum?

As members of the New York Police Department arrive at the taped scene outside the Guggenheim Museum, one asks, ‘How the hell did someone dressed like that get inside the museum?’ The response is pretty much ‘because it’s the arts’.

If the Met Gala is anything to judge by when it comes to the fashions adorning art attendees, then yes there is certainly an allowance for the fun, wacky and overdramatic. I’m thinking of Billy Porter’s 2019 Met Gala outfit featuring three-metre wings and a 24-carat gold headpiece.

Though with a wingspan like the one Vulture is sporting (up to nine metres according to some sources) the guards would likely ask him to tone it down and put it in the cloakroom.

The self-proclaimed artist also poses existential questions around the idea of contemporary art, repelled by the sheer lack of craftsmanship and grace as compared to his home universe in the Renaissance era.

After transporting from the portal, Vulture screams at the sight of String of Puppies (1988), a sculpture by US artist Jeff Koons – one of the most commercially successful artists in contemporary history.

Jeff Koons: there’s more than what meets the eye

In 1988, Koons was at the beginning of his glittering career. String of Puppies (1988) was presented as part of his Banality series – sculptures that are meant to be satirical in nature. It depicts a woman and a man, smiling and holding a string of eight blue puppies across their lap. The work itself is rather banal to behold, but there’s a good reason it’s positioned as Vulture’s initial uncomfortable encounter with contemporary art.

String of Puppies was the first work to become associated with a series of lawsuits surrounding the Banality show. The sculpture was based on the photograph, Puppies by artist/photographer Art Rogers. Rogers sued Koons for copyright infringement and the court sided with the original creator, adding that Koons’ ‘copying was so deliberate’ and also noting that ‘their piracy of a less well-known artist’s work would escape being sullied by an accusation of plagiarism’.

Yet, despite Rogers and many others winning their lawsuits against Koons in the Banality series, their works are still less recognised and valued than those of Koons. One could argue, in fact, that these scandals furthered placed Koons under the spotlight and increased his profile. In 2015, Guggenheim Bilbao hosted Jeff Koons: A Retrospective, containing many of the works that appear in Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse.

At least Vulture is unconvinced of Koons’ artistic credentials – exclaiming at the sight of Koons’ monumental Balloon Dog in the Guggenheim foyer, ‘You call this art?’ Without hesitating he slices off the head of the glistening stainless steel sculpture, only to reveal hundreds more miniature balloon dogs.

Supposedly, no one has seen the inside of Koons’ large-scale balloon dogs, though earlier this year an unfortunate mishap showed that the standard-sized sculptures are as hollow as they come – you don’t even get a hundred for the price of one (around $62,000).

In the film, Koons’ Lobster, which Christie’s sold for US$3.78 million (AU$5,547,800) in May 2022, and other ballooned sea-life are also treated mercilessly by Vulture. Gwen is flung among other valuable treasures, notably one resembling Koons’ Venus (2016-2020), which incidentally has been acquired for the National Gallery of Victoria’s permanent collection and is on display in the ground level gallery.

‘I bet it’s a Banksy!’

This action-packed fight scene at the Guggenheim climaxes with a helicopter falling through the museum and obliterating everything in its path. Spider-People from different universes hang on by their webs in an attempt to stop the destruction, and so it stops, suspended, just before landing on the crowd.

This tension in the cinema audience breaks into laughter as a fleeing member at the scene takes the time to shout, ‘I bet it’s a Banksy!’

Even if you’ve never heard of Banksy before, there’s a high chance you’ve seen works by the anonymous UK-based street artist. While many know him by his balloon girl murals, Banksy’s works are performative in nature and often only officially attributed to the artist after the fact through his social media platforms.

Banksy’s works are no doubt radical, but this identification (albeit humorous and more easily relatable for a non-art audience), feels like a missed opportunity to mention a non-Western artist, namely Cai Guo-Qiang.

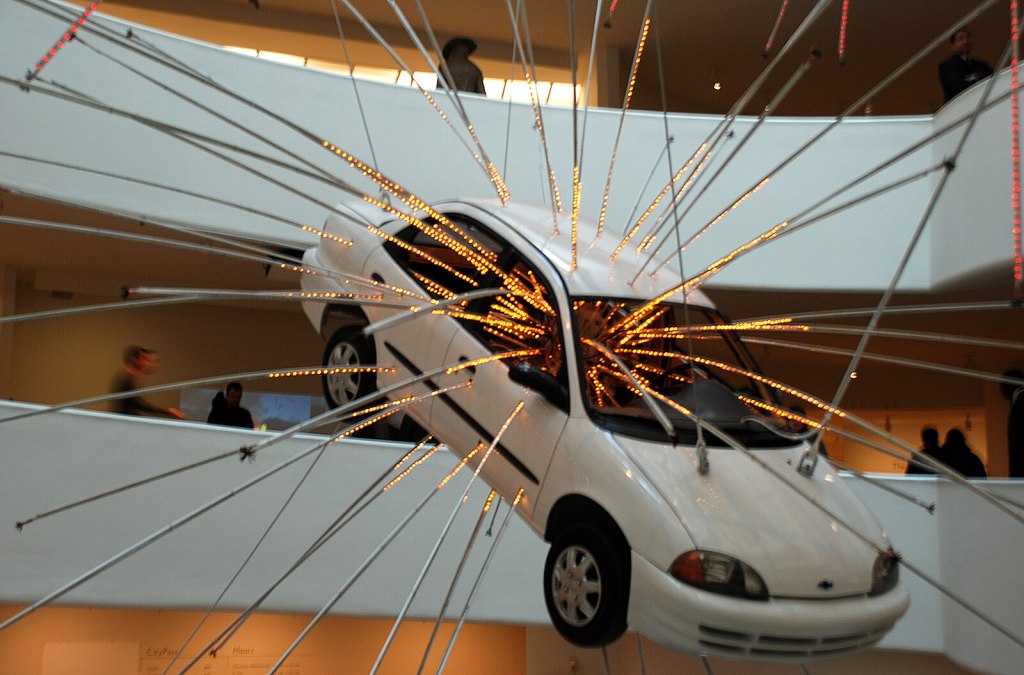

For me, the suspended helicopter speaks directly to Cai’s 2008 Guggenheim exhibition, which saw cars hung from the museum’s roof, caught in mid-motion with neon light rods erupting from each.

It’d be a more fitting reference, though perhaps this misattribution is part of the comic relief. After all, to see a Banksy in the making would be worth bragging about, even if it was during a fight featuring not one, not two, but three multi-universe superheroes.