Public funding will never conceive visionary projects like MONA or Tarrawarra. Private funding is essential to realising our cultural ambitions.

A continuing mistake we make is to fail to acknowledge our rich history of cultural development and the particular contributions of artists and arts organisations, successive governments, public and private corporations, individuals and philanthropic trusts to our cultural legacy.

Before governments assumed a greater responsibility, it was individuals like Alfred Felton, the world’s Paul Getty of his time and Australia’s philanthropic outlier, who died in Melbourne in 1904 without whom there would be a hugely diminished National Gallery of Victoria, who laid our cultural foundations. Similarly the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney can trace its origins to Australian expatriate artist, John Power (1881-1943), who left his personal fortune to the University of Sydney to inform and educate Australians about international contemporary visual art. And there are many other examples.

Perhaps for another occasion, I believe that it is nonsense to talk about the absence of a culture of giving in Australia. My observation is that there is a poorer culture of asking.

Similarly we should not ignore the fact that Australians have a long history of international cultural engagement.

I was reminded of this by the current exhibition at the NGV in Melbourne entitled Australian Impressionists in France. To quote the exhibition website:

‘Beginning in the 1880s and continuing into the twentieth century, many of the best and brightest art students left Australia to continue their studies in Paris…the Australians became part of the large community of French and foreign artists who were changing the course of art. Claude Monet demonstrated his Impressionist technique to John Russell; Charles Conder trawled the cabarets of Montmartre with Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec; and Vincent van Gogh considered Russell a friend. In France, Australian artists engaged in personal and artistic exchanges with artists from around the world.’

Just as we shouldn’t overlook the contributions of our forebears in realising our cultural ambitions, we must recognise the significant roles played by those in the commercial and unsubsidised arts sectors, and private arts benefactors and entrepreneurs.

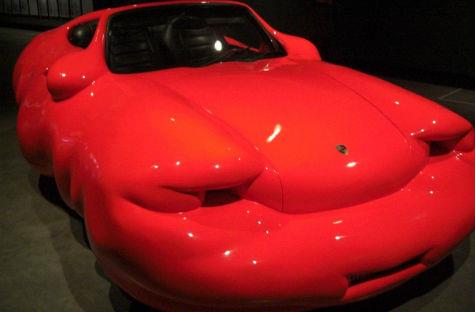

For example, it is difficult to imagine a government agency conceiving, let alone being allowed to pursue and construct projects like MONA in Hobart, Tarrawarra Gallery in the Yarra Valley, White Rabbit in Sydney as well as many other private places established for public purpose. These risky and daring initiatives have changed the way we think about art museums, programs, education, curatorship, outreach and taste. In each case, a private ambition has cascaded into a deep community of public pride.

Likewise, the groundbreaking contemporary arts projects made possible by John Kaldor have given Australians the opportunity to share the visions and creativity of some of the world’s leading artists.

Many others have quietly, and occasionally noisily, donated works of art to art museums, supported musicians and writers, and helped with the construction of some of our major cultural infrastructure, such as the National Portrait Gallery and the National Gallery in Canberra. There are examples all across the nation.

I think that we can expect to see a greater commingling of private and public funding in the arts. I know that some fear that this will be as a necessity as a consequence of or even a pre-empting of a withdrawal of government from the sector. Whilst that is conceivable, I think that it is more likely that the grant assessment processes of organisations like the Australia Council will be sought by those wishing to support the sector but could never find the economies to set up their own peer review and grant making arrangements. Leveraging off existing processes, a larger number of grants could be made across and between all art forms.

Some of the relationships between subsided and commercial arts and public-private linkages are not always immediately obvious. For example in a recent article in The Australian Matthew Westwood wrote:

‘An ambitious commercial musical like King Kong owes its existence to private enterprise, but it, too, draws upon the theatre craft and skills developed in national training institutions and the subsidised arts sector.’

We need commercial arts entrepreneurs and we need graduates from schools such as Wollongong’s Creative Arts Faculty to be players in our national culture.

This story is an excerpt from a speech given by Rupert Myer at the University of Wollongong. For more from him on international engagement read the section on Selling Brand Australia. The full speech can be accessed at the Australia Council.

Image: Fat Car by Erwin Wurm from MONA