A waiver was required for Carsten Höller, Giant Psycho Tank, Image viw WikiArt

The immersive art environment has become increasingly de rigeur and as audiences we have become bolder and more expectant to be engaged on a number of levels by our “art experience”.

However, with that comes implications. Boundaries – despite the perception of the boundless immersive zone – often need to be set. For example audiences may be channeled along a pathway through a work, warned of a strobe lighting effect or to watch their footing in a darken space.

In May 2015, visitors to James Turrell: A Retrospective exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA), were required to sign waiver to engage with the centerpiece of the exhibition Perceptual Cell: Bindu Shards (2010).

It didn’t seem to perturb anyone as the ticketed experience sold out immediately; nor did it worry the NGA who purchased the work.

James Turrell’s Bindu shards (2010) Perceptual cell: fibreglass, metal, light program. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra purchased 2014. Supplied / courtesy artist and NGA.

To experiencing Turrell’s orb-shaped installation, the viewer was positioned by a lab-coated assistant inside the chamber, given a panic button and then immersed with a spectrum of rapid strobe and pulsating light for 10-minutes, what Turrell described as and experience ‘behind the eyes light’.

Turrell’s work is part of a growing trend, particularly in the more litigious American environment. When Carsten Höller’s exhibition Experience was presented at the New Museum in New York in January 2012, viewers had to sign a waiver of liability to experience his 102-foot slide.

I can’t remember signing one when QAGOMA presented a similar slide in their 2010 exhibition 21st Century: Art in the First Decade. A spokesperson from the Gallery confirmed: ‘Visitors to Carsten Holler’s Left/Right Slide were not required to sign a waiver. The Gallery required visitors to read the conditions of experiencing the artwork and note that it was at their own risk. This was based on legal advice the Gallery received at the time.’

Have international museum standards change during the intervening years or have countries, such as America, become more vigilant in the fear of litigation and web of public liability?

A waiver was also required for Höller’s mirrored carousel at the New Museum; but not when it was presented at the National Gallery of Australia recently.

It appeared that the waiver was the paper de jour at the New Museum’s show – another was required to experience Höller’s Giant Psycho Tank, a sensory deprivation pool and another for a psychedelic flashing light installation.

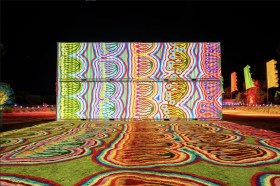

The current example in Australia is at Dark Mofo, Hobart’s art and food festival that promised to take you to the dark side.

One artwork this year presented by Melbourne artist Byron J. Scullin and Supple Fox immersed participants in a bass frequency that was so deafening it required viewers to sign a waiver before entering and apply two layers of ear protection.

‘Bass Bath participants sign a waiver declaring that they are responsible for any adverse health effects that they may experience after participating in the artwork, confirmed a Dark Mofo spokesperson adding, ‘Those headphones are effective!’

The physicality of the art experience was a theme across Dark Mofo for 2015. Anthony McCall’s work, which did not require a waiver, enveloped viewers in a darkened room with kinetic light sculptures, and at the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) Marina Abramović: Private Archaeology encouraged viewers to become part of the art experience by stripping their belonging and counting rice, a mental and physical disconnect.

A darkened slightly misty space defines the work of Anthony McCall but no waiver required at Dark Mofo (2015); photo ArtsHub

MONA has built its reputation subverting the traditional gallery experience. Celebrated for its unconventional entry that takes people from a tennis court and delivers them at a gallery-embedded bar; its gallery’s black walls carry this passion for the dark side and “breaking rules” from ethos to presentation to marketing.

An aspect of that marketing is the museum’s logo, two orientations of a cross. A sculptural version of it in granite stamps the tennis court in case you were confused if you had arrived in the right place. At night, however, it disappears with opening night crowds at an exhibition, and hence finding a place in this conversation of waivers and artworks.

After falling over the granite MONA logo, I have the evidence of a black eye that risks were not just in the artwork. I was not alone. My inelegant tumble was welcomed with a cheer by those waiting to catch the MONA Roma ferry: ‘And there goes number five!’ I was comforted to note on rising that MONA staff were heading my direction with chairs to attend to the obstacle in question.

MONA’s unconventional entry defines its unique position as a museum that has become internationally celebrated; Image source Think Tasmania blog

Despite the black eye, I advocate the unbounded viewing experience and join in the celebration of MONA achievements and programming – but it presents a timely question.

Where do we set the boundaries – the waivers – in this ever-growing desire for our museum experiences to be immersive?

Any event or public venue today has to be cognoscent and compliant with Occupational Health and Safety (OH&S) rules, but is also very aware of a zeitgeist that drives the popularity of these events. Keeping it in perspective and getting the balance right is the challenge.