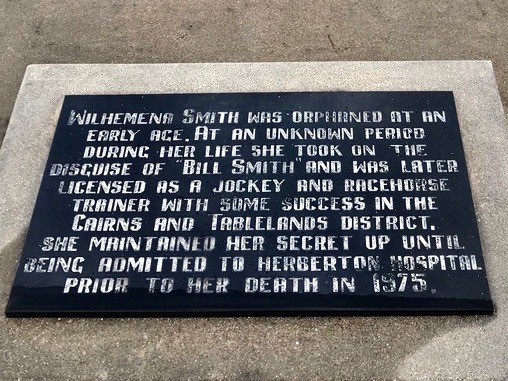

In a cemetery in North Queensland lies ‘Wilhelmina “Bill” Smith, “Australia’s first licensed female jockey”,’ who ‘at some point in her life took on the disguise of “Bill Smith”’ – according to the impressive headstone, at least.

The unveiling of the headstone in 2005 was intended as a celebration of a life that may otherwise have passed without much attention – a well-intended act of charity to, as some saw it, rectify a piece of racing history. ‘Bill Smith’, as he was mostly known, had died 30 years earlier in 1975. He was buried in an unmarked grave with no fuss, as he had requested.

So, was this recognition or was it an erasure of the individual who lay beneath?

My uncle, a former horse trainer from North Queensland, had told me years earlier about a jockey who always arrived at the track with his riding gear under his street clothes, and who never showered or changed with the other riders. This story was couched in terms of Bill being a woman who simply wanted to ride horses professionally and found a way to achieve that goal. But Bill had lived as a man long before he arrived in North Queensland and continued to do so until the end of his life.

Listening to my uncle’s story, I thought Bill must have been transgender, but I didn’t say it. It simply wasn’t a discussion to have with my uncle in an era when the world offered a staunchly binary view of life. The terms ‘misgender’ and ‘deadnaming’ were not yet in popular use and wouldn’t be until some time after the unveiling of Bill’s headstone. Today, I use he/him pronouns to reflect the gender Bill appeared to identify with throughout most of his adult life, albeit with qualification.

Bill Smith’s real life was shrouded in mystery and contradictions. Was Bill really a woman disguised as a man, living ‘under false pretences’, as some have suggested? Or was Smith ‘a feminist hero’, as one racing identity proclaimed, presenting as a man only to break through the societal restrictions of gender assigned at birth? Of course, there was another possibility – one seemingly not considered at the time by most. Even those few who had first-hand knowledge of Bill don’t seem to know the answer with certainty or consensus, highlighting the danger of labelling anyone who can no longer speak on their own behalf.

Available information about Bill is scant, and what there is, is full of contradictions. According to Laurence Murphy, in his 2020 e-book Under False Pretences, Bill Smith was born Wilhelmina in the US in 1886. ‘She’ came to Melbourne with her family as a child, but her mother died when she was young, and her father was described as having been brutal. Wilhelmina started dressing in boys’ clothes to get work from a young age. She died in 1975, aged 88, having confided some of her story to a Nurse McConnell, who is quoted in Murphy’s 2020 publication.

Other sources claim that Wilhelmina was born in Western Australia, while some say Sydney. Dates cross over; locations and events are blurred at times. There is a lot of misinformation and confusing details about the individual buried under the names Wilhelmina/Bill Smith.

Whether Bill identified as transgender is not for me to say. I was more interested in what it meant, what it means – that the possibility was not even considered by those who wanted to finally acknowledge Bill. Would there have been the same push for recognition and memorialising if it was known that Bill was not ‘the first woman jockey’, but the first trans jockey? Was it naivety or wilful ignorance that so many LGBTQI+ people throughout history were invisible to all but those who could see something of themselves in individuals like Bill?

I was also interested in the lengths someone like Bill may go to avoid rejection, violence, disadvantage – to make others feel comfortable and not disturbed by their perceived difference, to stay small and unseen. We are at a point in history when we are being asked to examine attitudes and beliefs about gender in unprecedented ways. I have had to reflect on my own conscious and unconscious biases, stereotypes and beliefs, something core to my previous career in cultural safety education. Cultural safety originated as an Indigenous philosophy from the Māori people of Aotearoa/New Zealand and, as a philosophy and way of being, it asks us all to be regardful of any perceived cultural differences between ourselves and those we encounter in our lives.

Read: Yes to visibility and queer (re)tellings

Queer culture – like other cultures, including those based on ethnicity, religion, disability, age or socioeconomic backgrounds – has the potential to become ‘othered’, discriminated against, marginalised and divided. One way to diminish somebody is to fail to see them or make it safe for them to be seen. This is what struck me when I first heard of Bill’s story and people’s responses to learning about his assigned gender at birth.

I believe that Bill and others like him should be recognised perhaps more for their courage to challenge gender norms in their own way rather than for any label others may apply. Since diving into Bill’s story, I have been challenged by my own changing views and beliefs; I grew up using words and terminology that are now insensitive and inappropriate. Understandings about sex, sexuality and gender identity are constantly being debated and redefined.

Bill’s story remained a snippet of information in my head until I was gifted a writing mentorship with acclaimed author Inga Simpson. I hadn’t intended to write about Bill for my first novel, but he kept inserting himself into my thoughts – a fictional Bill Smith, at least. I didn’t have enough credible information about the real Bill to write anything but fiction, but I did have my own family connections to racing and North Queensland. It was Inga who pointed out the potential significance of Bill’s story as part of queer history, as much as it was to racing history or the iconic stories of the Australian bush.

In the end, Bill’s story is a human one – a story of the need to feel connected, loved and remembered. Bill lived a life of risk – of constant fear of exposure, rejection and possibly worse. There was something fearfully brave and bravely fearful about the way he lived his life, and that alone is worth recognising. His story, however, is about more than an individual. It is a glimpse into a part of Australian history covering periods of great social change and upheaval, and the importance of simply having witnesses to a life lived.

Kerry Taylor is the author of Mr Smith to You (Affirm Press), out now.