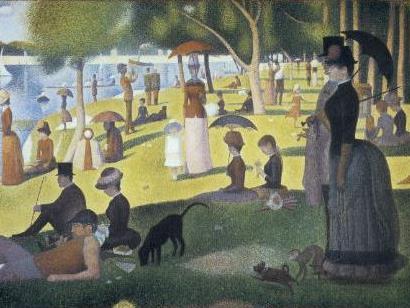

George Seurat, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. Image Creative Commons.

There is a scene in the film Ferris Bueller’s Day Off where, on a sunlit day in downtown Chicago, a couple and their friend amble through the halls of an art gallery. The three of them wander and pause before a variety of works by Edward Hopper, Matisse, Picasso and Rodin.

The couple sneaks away for a kiss, bathed in the blue luster of Mark Chagall’s American Windows. Their friend Cameron Frye (Alan Ruck) is left alone to become enraptured by Georges Seurat’s celebrated A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

Cameron stands before an unassuming tableau; families enjoying a sunny day out by a river. Parasols and boat sails answer each other from the water and grass. The women wear the less ostentatious crinoline dresses of the latter 19th century and the men sport top hats and walking sticks. They stroll or lay supine and let their attentions wander into their surroundings. It captures a lifestyle of both formality and leisure, reflected in the artist’s generous use of colour yet meticulous attention to light and shade. The young man is drawn to a figure in the mid-ground, a little girl in a white dress. She stands close by her mother, holding her hand. She is the only subject in the entire painting whose attention seems to directly address the viewer. The two of them lock eyes, and as they seem to study each other in swelling detail the young man arrives at some revelation.

What simmers in this scene between is the issue of loneliness and self-confrontation. As the camera view increasingly magnifies the mirrored scrutiny between the two subjects, Seurat’s pointillism method of painting reveals of the girl an image that falls out of sense and coherence, as does Cameron’s sense of himself.

What Cameron experiences is a cautionary tale common to many. Like Cameron, we often end up making the best sense of ourselves through our relationships with others. As Seurat’s little girl is a daughter clutching her mother’s hand, Cameron is given clarity of himself through his friendship with Ferris.

There is nothing foolish in this. Our relationships often represent the greatest source for enriching our lives. The question is in ensuring to likewise maintain an independent sense of ourselves so, unlike Cameron, when challenged into self-analysis, we can avoid falling into a lonesome obscurity.

This self-analysis permeated the philosophical milieu of ancient Greece. The Delphic proverb Know Thyself was at once a call to humility, but furthermore a herald to the inherent value of self-examination. As emphasised by the Socratic maxim that the unexamined life is not worth living, the implicit wisdom is that there is elevation in taking the time to question and understand ourselves that is inseparable from living well.

One worthwhile fruit of this process is the firmer foundation of self-understanding that can prevent us from falling out of sync, or worse, becoming completely lost. If only Cameron Frye had known this.