Image: londonvisitors.wordpress.com

At what point do we move beyond judgement to celebration? And, how do you (if ever you do) recalibrate the past through contemporary storytelling?

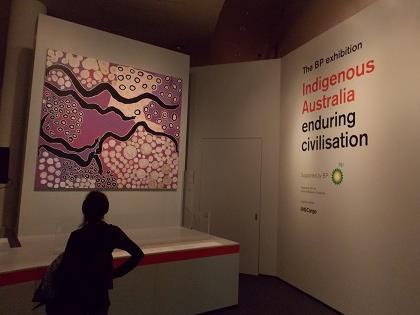

They are fundamental questions that lie central to an exhibition that has opened this week at the British Museum (BM) – a joint project with the Australian National Museum and the first in fifty years to trace the history of Indigenous Australia.

Enduring Civilisation was always going to be a challenging exhibition to present. The exhibition was largely curated from the BM’s holdings of ethnographic artefacts collected during colonial times. As one of the older collecting institutions, this understandably raises issues of repatriation in our contemporary milleu, and the rightful ‘ownership’ and cultural lineage of the Museum’s holdings.

Did this exhibition manage to pull through the ethical sea and address the topic? Reviews are mixed.

It has been a very different tone this week to Australia’s last grand jeté on the London stage. In 2013, the highly anticipated Australia exhibition opened at the Royal Academy of Arts to acidic remarks such as: ‘light-weight, provincial and dull’, and ‘reminiscent of liquid crap’ and ‘poverty porn’, comments by award-winning Sunday Times journalist Waldemar Januszczak that quickly went viral.

Despite the sensation of Januszczak remarks, the exhibition, regardless, felt flat and was lampooned for its curatorial failings.

In contrast, it is not the selection of work – the curatorial integrity – that is being called to question with the opening of Enduring Civilisation. Rather the comments are two-fold: that lack of didactics fail to support and extend the works on show (which could be easily addressed) and secondly, that is it an ‘all-too-familiar account of dispossession, malfeasance and massacres by the British’, as touted by journalist Alastair Smart of The Telegraph (UK).

Smart feels that by ‘undervaluing millennia of achievement, this show feels like yet another injustice meted out against Indigenous Australians’, and one that is focused more on slamming British colonial rule.

Smart complains of tiring of the pummelling of woe, which reached a crescendo, in his opinion, with the story of Maralinga, the joint British-Australian nuclear testing program of the 1950s on Aboriginal land.

Respected Australian writer Christine Nichols, who has long reported on Indigenous art, took a different opinion of the presentation of this material. While acknowledging it as a ‘festering would’ she said: ‘While admittedly this is dealt with in reasonable depth in the catalogue, the text accompanying the exhibition simply states that some Aboriginal people were “removed from the arid centre of Australia when the land was needed for atomic testing”.

Nicholas continued: ‘Reading between the lines is quite possible for some aspects of this exhibition, but this anodyne statement nullifies that possibility. Maralinga and the atomic testing program in general remain unfinished business, implicating both the British and Australians, and it seems unduly timid not to have served this up to the Brits a tad more forcefully.’

Is the UK ready to hear these stories?

It is questionable if Australia is ready to tell these stories internationally when it still struggles to address them fully on home soil. But as the arbiter, it is the role of our museums to educated and expand understanding using documentation.

The other thorn that sits in the side of this exhibition is the topic of repatriation, with some communities using it as a moment of traction in a long debate.

Such issues are brokered over long conversations and, indeed, sit somewhat outside rightful ownership to the realm of collective cultural protection. A friend recently made comment to me that the shared housing of the world’s antiquities is about spreading the risk – an argument supported in the light of terrorist destruction of cultural heritage, or its loss through natural disaster, as we have just witnessed tragically in Nepal this week.

Nichols, while tipping her hat to this extremely layered and sensitive topic, keeps it in perspective and within the format of the museum exhibition environment. She writes: ‘As an exhibition, Indigenous Australia: Enduring Civilisation hovers uneasily between being a fine art exhibition showing the diversity and sheer visual and sociocultural potency of contemporary Australian visual art practice, and older-style ethnographic survey of objects excavated from the archives of the British Museum, arranged in rows behind glass cases – as is the case with various weapons including spears, spear heads, boomerangs and so forth.

‘That exhibition style, albeit in this context in post-modern garb, is redolent of the “Wunderkammer” (literally “Cabinets of Wonder”) – European keeping-places for objects pertaining to specifically-themed collections of yesteryear. While the relationship between these two disparate approaches is not one of seamless fusion, it certainly makes for an exhibition that’s good to think with,’ she continued.

Nichols suggests that the flaw, perhaps, lies more in how we approach material of this nature rather than the material itself. Exhibition such as Enduring Civilisations, can only be deemed important for raising the dialogue to broader audiences.

Mixed reviews

The Guardian’s (UK) Jonathan Jones gives the exhibition five stars saying that the BM doesn’t shy from its ownership of many controversial artefacts. He writes: ‘Far from treating Aboriginal art as an aesthetic fetish, this eye-opening show sees it as part of a living and enduring civilisation with a unique understanding of humanity’s place in nature.’

Clearly, at some expense, this exhibition has chosen to be rigidly diplomatic. Truthfully though, could we expect anything else? But it does seem like an opportunity has been lost. The material is there, the stories are there in those objects, but the translation of those stories seems to have been lost in heavily abridged labels.

From the accounts published to date on this exhibition, it seems to teeter perilously between brilliant and long over-due and another faux pas easily avoided. The credible difference between the exhibitions Australia and Enduring Civilisation appears to be weighing up as a curatorial one. The latter a hit while the former a miss. The research and collaborative partnership between the British Museum and the Australian National Museum can only be saluted.

One might argue the jury is still out, to be better assessed when the exhibition transfers to Canberra in November.

Indigenous Australia: Enduring Civilisation is at the British Museum until August 2.