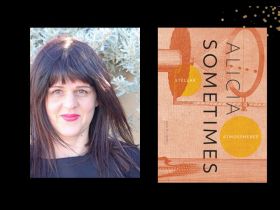

Image: Footscray Community Arts Centre

How good is good? How can community art be evaluated outside of the context in which it occurs? These are questions every community-engaged practitioner should have reflected on at some point in their career. No doubt we ask ourselves often; amongst our colleagues and during the challenging hours when a project takes an unexpected turn.

Recently Footscray Community Arts Centre (FCAC) hosted Practitioners’ Voices, a two-day professional development forum for community-engaged artists and practitioners initiated by Castanet*. The conversations were political, strategic and rigorous, and the voices diverse. No more so than when the topic turned to evaluation and how we measure our work. Throughout the discussion I noticed, not for the first, time that our concerns about evaluation is shifting, fragmenting into a narrower focus that moves us away from what we are trying to do: work with communities and drive social change.

For me it often seems that the discussion is being tied almost entirely to outcomes, in particular the hard numbers and subjective notion of quality. How many participants? How many audience members? We can answer these questions in neat statistics but they only tell one part of the story. In 2013, FCAC delivered 1828 activities with more than 2000 participants, not including audience members. The outcomes of these activities are beautiful, diverse, high impact and community engaged. They tell a story absolutely worth telling however, when describing how important our work is, I often feel like the numbers are what people respond to (both in and outside the CACD sector), not the depth of the project, the passion of the participants or our impact within the community. With increasing interest from our funding partners, we are having more success in resourcing the evaluative components of our programs, these evaluations focus on the outcome and rarely the impact. This is not to say that outcomes are not important, but it does not necessarily give us a full picture of the impacts, and therefore the true purpose of our work.

And then there is the question of quality, often measured in ‘excellence’. There should absolutely be a focus on excellence. Who wants to make work that is anything less than excellent? But as a measure of a project’s success it is fraught. What excellence is to one community may be entirely different to another. For excellence to be meaningful to community-engaged arts it needs to go beyond the outcome and process to also consider practice, partnerships and the ways that the work impacts in community settings. Best practice is excellent practice. The term may come from funding bodies but as a sector we need to own the term ‘excellence’ and decide for ourselves, within the evaluation frameworks we have, what excellence means in relation to the sophisticated and delicate work that is community engaged arts and cultural practice.

What is missing from this conversation is how we are succeeding as a sector. Anecdotally, there seems to be a decline in collaboration. Organisations are bunkering down, having fewer conversations about the big picture impact of the sector and instead talking more about their own work. Perhaps this is driven from a fear of becoming one of the increasing numbers of smaller organisations that are being defunded; perhaps it is the shift in the political climate.

Collaboration is integral to community-engaged arts practice. What we do is not one project, artist or organisation working in isolation. This practice is, in essence, collaborative, with the community at the centre. By fracturing the work that we do, by being unspoken competitors in numbers, money and excellence, how can we achieve the social change that we are striving for?

We need to be having conversations about the ways we are each working with communities across Melbourne, Victoria, Australia so that as a sector, we can recognise and understand the gaps. We must know more about each other’s work. I should be able to speak to the work of multiple practitioners when securing funding or private and corporate partners, to demonstrate that the fabric of community arts and cultural development work is strong. Perhaps not always united, but certainly connected and that we understand the work and ourselves we do in a bigger context.

Finally, we cannot rely on funding bodies, membership-based organisations and professional development opportunities to bring us together. It is time for more practitioner-led conversations like Practitioners’ Voices. It is essential that the new generation, mid-career and older generation practitioners are active in the development of the new era for community arts and cultural development practice. We all have a responsibility to connect with and support those that are interested in working in the sector.

It is only through seeing it holistically, that we will understand the impact of our work; it is the process we go through, the participant experience, the outcome, the audience experience, the advocacy work we do across the communities we work with, the partners we bring on board and the sector we are a part of. Some of that can be measured in numbers, some of it can’t and, most importantly, the social change we hope to be drive cannot ever be attributed to one single project, artist or performance. Quite simply as Contact Inc states, we are better together.

*Castanet is a network of Victorian arts organisations, artists and government agencies in partnership with Arts Victoria. Castanet supports community arts and cultural development in Victoria by offering professional development programs as well as planning, brokering and information services to anyone who is interested in developing community arts projects and activities.