Most would agree that French Post-Impressionist artist Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) is problematic for his colonialist and misogynist tendencies, which are both outdated and unwelcome. However, the man is not the art. This is the angle that the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) is taking for its forthcoming exhibition.

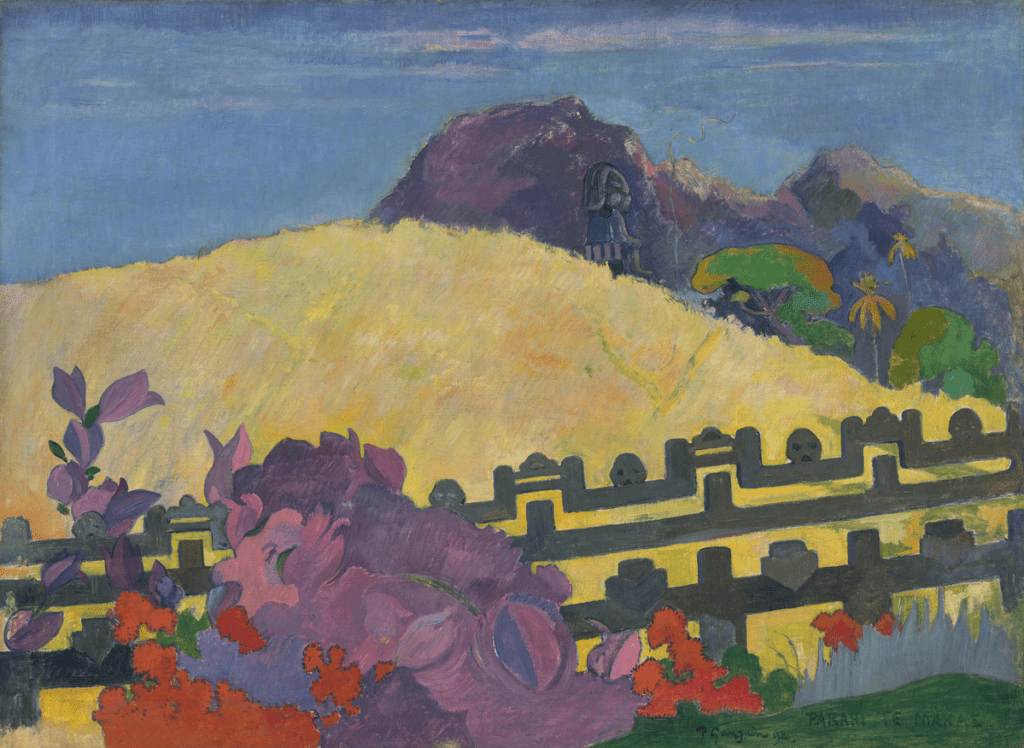

The Gallery has announced an Australian-first exhibition of over 140 of Gaugin’s iconic works of art, opening June 2024. The artist is of course famed for his sensual visions of Tahiti, which are what writer Charlotte Higgins aptly describes as “prelapsarian“.

It is a tone hinted at in the title of the NGA show: Gauguin’s World: Tōna Iho, Tōna Ao, which riffs off Gauguin’s knowledge of the Tahitian language. Dr Hiriata Millaud’s exhibition catalogue essay explains, ‘Tōna Iho meaning Gauguin’s soul, spirit, heart, thought, ideas, opinions, views; Tōna Ao meaning all what constitute and shape Gauguin’s world’.

There is a kind of zeal that comes with a colonial perception of ownership – aka the myopic adoption of another’s as “my world”. But the double entendre embedded in this exhibition’s title also speaks to an expansive embrace of life in all its nuances – and, in Gauguin’s case, a life creatively celebrated.

This, however, is a deeply loaded exhibition from the outset, and the Gallery says it is not hiding from those darker conversations. It has been curated by 19th century French art scholar Henri Loyrette (former Director of the Musée d’Orsay and the Musée du Louvre, Paris), with Dr Lucina Ward, NGA’s Curator of International Art, wading in.

ArtsHub catches up with Ward, who says Gauguin is ‘a really complex character, and the self-mythology needs to be taken with a grain of salt’. She continues, ‘[With] the lens of the 21st century, we may know him for the wrong reasons – and we’re completely acknowledging that, and facing up to that. There’s no point not talking about these things. [But] Gauguin is one of those artists in the 19th century, that if there were no Gauguin, 20th and 21st century art would be really, really different.’

Jump to:

Why Gauguin? That’s what everyone’s asking … again

‘It’s very interesting to see what legacy Gauguin has left in French Polynesia versus the rest of the world. And we think this is simply an opportunity to bring together extraordinary works – and we deserve to know more about Gauguin – the good, the bad and the ugly, and it’s mostly good, I think,’ says Ward.

Ward explains that Gauguin’s use of materials is extraordinary. ‘That knowledge of colour theories, that willingness to move away from painting to ceramics, amazing drawings, even better prints, and absolutely terrific carved wood sculpture … while I find the man terribly problematic, what I do find extraordinary is, he was an artist who travels everywhere, especially in a 19th century context.

‘He’s born in France, grows up in Peru, returns to France, goes to Copenhagen, then goes to Brittany, and Martinique (in the Caribbean), and then imaginatively goes even further – he goes to Egypt, he goes to the French territories, and his motivation for coming to the Pacific is partly because of his competitiveness with Van Gogh. If that relationship hadn’t ended so disastrously, there may never have been a studio of the tropics,’ says Ward.

It is that very peripatetic frame of view, in particular Gauguin’s Pacific odyssey, that is the focus of this exhibition. It’s a period that produced his most celebrated paintings, but also his most controversial when considered via a 21st century lens.

‘Like other contemporary and historic artists, Gauguin’s life and art have increasingly and appropriately been debated here and around the world. In today’s context, Gauguin’s interactions in Polynesia in the later part of the 19th century would not be accepted and are recognised as such. The NGA will explore Gauguin’s life, art and controversial legacy through talks, public programs, a podcast series and films,’ NGA Director Nick Mitzevich says of his decision to stage the exhibition.

When did the dialogue start to shift around Gauguin?

Arguably, one of the first Australian blockbusters (before the term was even coined) to include Gauguin’s work was the 1939 exhibition French and British Modern Art at Melbourne’s Town Hall (where he was shown along with Picasso, Bonnard, Braque, Cézanne, Matisse, Van Gogh, Seurat, Rouault and Modigliani). Between then and now, there have been other sweeping exhibitions.

At the NGA alone, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cézanne and Beyond: Post-Impressionism from the Musée d’Orsay was presented in 2009-10 under director Ron Radford. It included nine Gauguin paintings, but did little to advance the conversation beyond blockbuster mythologising.

The NGA pushed out of the pandemic with a roll call of big-hitting names with the major international exhibition, Botticelli to Van Gogh: Masterpieces from the National Gallery, London (2022), again including Gauguin.

Read: Your 2023-2024 summer exhibition planner

Conversations started to shift with the London National Gallery’s deep dive into Gauguin’s self-obsessed portraits with the exhibition Gauguin’s Portraits (2009), pointing to his narcissistic personality, and a year later Tate Modern’s 2010 exhibition Gauguin: Maker of Myth.

Charlotte Higgins (The Guardian) wrote at the time: ‘He was a fabulist and shameless manipulator of the truth, as well as a canny self-publicist, the sort of self-conscious user of shock tactics we might associate with a modern generation of artists.’

Perhaps the closest precursor to the NGA show, however, was Paul Gauguin – Why Are You Angry?, presented by the Alte Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin last year (2022). Like the NGA show, it opened up conversation by including works from contemporary by artists, such as Angela Tiatia (New Zealand/Australia), Yuki Kihara (Samoa/Japan), Nashashibi/Skaer (UK) and Tahitian activist and multiform artist Henri Hiro (French Polynesia).

This new NGA exhibition picks up on that global zeitgeist, interrogating the colonialist dream of an earthly paradise up for grabs. It is being described by the Gallery as one of its ‘most ambitious exhibitions’ ever staged – that ambition being less about freight, loans and logistics and more about navigating the narratives around Gauguin, and how those histories sit within a very different world that is today.

How collaboration opens up sketchy histories

Ward and her colleagues have worked closely with Musée de Tahiti et des îles, as a lender of important 19th century Marquesan sculptural works, helping to contextualise Gauguin’s years spent in French Polynesia.

The NGA has also deliberately engaged the art collective Sistar S’pacific (aka artist Rosanna Raymond) to recreate the SaVĀge K’lub, which was first presented at the 10th Asia Pacific Triennial at Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art. Visitors will have to move through it to enter Gauguin World, so it effectively acts as a prequel to the main exhibition’s narrative.

‘We’ve engaged Rosanna to form a different sort of intervention,’ explains Ward. ‘And then we’re going to look at a couple of pivot points, to suggest a prehistory of Gauguin.’ The team will rehang elements of the Pacific Collection as another entry pathway to the exhibition.

Ward adds: ‘At one stage [Gauguin is] inspired by the Buffalo Bill character and starts wearing his hair long, and when he gets to Papeete for the first time, they think of him as being a man-woman (māhū). So we’re going to suggest, within this space, some of those other legacies. It’s great to be able to finally talk about, and open up those conversations, but also to manage them in a way that expands knowledge.’

Rosanna Raymond will present an in-conversation with pioneering feminist scholar and author of Gauguin’s Challenge: New Perspectives after Postmodernism, Norma Broude, in the talk titled: We need to talk about Gauguin? as part of the exhibition’s programming in March.

Read: Exhibition review: Louise Bourgeois, Art Gallery of NSW

While in June, a Gauguin Symposium will bring together exhibition curator Henri Loyrette, alongside Hiriata Millaud (Head of the Archives in Tahiti and Adviser to the Vice-President of the Government of Tahiti and overseer at Tahiti Tourisme), Nicholas Thomas (Australian anthropologist, Director of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge), Miriama Bono (Director Musée de Tahiti et des Îles), and Vaiana Giraud (Gauguin expert and head of communications at Maison de la Culture in Papeete).

The Gallery adds, ‘Gauguin’s World provides an opportunity to reconsider Gauguin from a holistic perspective.’

More on understanding Gauguin’s Pacific odyssey

The 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle played a huge part in the Gauguin narrative, where he was drawn to the Tahitian, Polynesian and Cambodian pavilions, and made the decision to leave Paris. He had essentially deserted his wife Mette-Sophie Gad and five children seven years earlier, so the move was in keeping with his self-propelled and narcissistic view.

He arrived in Papeete, Tahiti in 1891, but it was hardly the exotic island and cheap living that he mythologised. The illusion of his success in the Paris art world took him back briefly in 1893, but he quickly returned and stayed. Struggling financially, he moved to Atuona in the French Marquesas, 1600 kilometres (1000 miles) north-east, in 1901, where the teenage girl Marie-Rose Vaeoho became his “companion” until his death in 1903.

She bore him a daughter, and he also left an illegitimate son behind in Tahiti. Gauguin suffered from syphilis, eczema and alcoholism, and was addicted to laudanum, opium and morphine – it was an overdose of one of these that probably caused his death, although it was officially labelled a heart attack. This reality has featured little in the shining glory of his paintings, or past exhibitions that have perpetuated the myth of a lived paradise.

Read: Swelling interest in Pacific arts

When he died, most of his paintings were auctioned off in Atuona, with many of his letters and objects he collected burned because they were considered pornographic. This has meant that much information from those last years has been lost. This new wave of exhibitions around Gauguin all aim to offer a fuller story.

Gauguin’s World: Tōna Iho, Tōna Ao will open at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra on 29 June – 7 October 2024. It will be a ticketed exhibition.

The exhibition is delivered in partnership with Art Exhibitions Australia.

Conversation: We need to talk about Gauguin? | 23 March 2024

Gauguin Symposium | 28 June 2024

Gauguin’s World pulls together master works from collections worldwide, including 17 pieces from the Musée d’Orsay Paris; major works from the National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh; the National Gallery of Art, Washington; the Philadelphia Museum of Art; the Cleveland Museum of Art; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Louvre, Abu Dhabi; the J Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and the National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo.

Following Canberra, Gauguin’s World will be presented at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, late 2024.