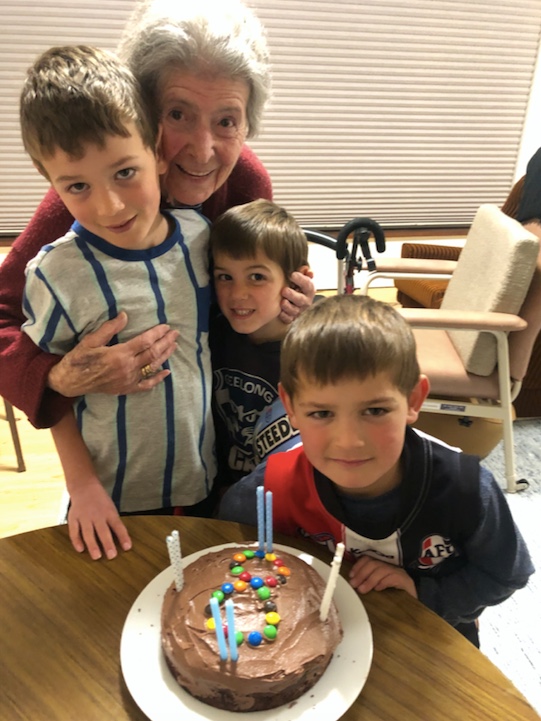

Sitting in the corner of a darkened hospital ward, I gently tap away at the screenplay of my mum’s life story while she lies in a bed alongside following a haemorrhagic stroke. The doctors haven’t given Mum, who is 92, much chance. They decided she was too frail for any surgical procedure as she’s drifted in and out of consciousness. To think only two days earlier, we’d celebrated her grandson’s eighth birthday. She’d joyously sung “happy birthday”, eaten chocolate cake and posed for photographs with her three tiny descendants, her hair full, her eyes glowing.

After emigrating from Greece in 1956, Mum was unable to have children of her own. Her brother then gifted her a child in 1974 – me – to raise in Australia. I didn’t learn this truth until 1999 when I discovered I also had two older brothers in Greece. Since 2020, I’ve been working to adapt this intergenerational, international story to the screen with Australian filmmakers. The narrative has two voices: my own journey of identity and self-discovery, alongside Mum’s heartbreaking story of immigration and infertility.

This unpublished chapter began when I received a call on an unseasonably warm August morning. It was Mum’s gardener, organised as part of her care package, who mowed her lawns and trimmed her trees every first Tuesday. ‘You better come,’ he told me. ‘Your mum’s normally happy to see me, offers a drink, has a chat. Today, she’s very confused and struggling to speak and walk.’

We spent the first night in Emergency with Mum trying to speak three languages: Greek, English and an incomprehensible combination of the two. The hope was for a straightforward undiagnosed urinary tract infection, but CT scans showed an enormous white metastasis of blood in Mum’s brain. A grim-faced neurologist spoke to me soberly and without censorship about quality of life and decisions about resuscitation and intubation. I was cast back to Dad’s passing in 2016 that left Mum alone at home.

‘Older people’s brains tend to shrink, so there’s more room in their skulls to absorb the swelling,’ the doctor told me. ‘Frankly, a younger person wouldn’t have survived what your mum’s gone through.’

The doctors said they would support Mum in the hope the swelling went down and functions returned – paracetamol, checks of blood pressure and body temperature. But that was the extent of it – for a massive cerebral haemorrhage.

It was a fitful night’s sleep, worrying about Mum. But my spirits were lifted on Wednesday morning in the general wards: Mum was weak but responsive, struggling to focus and trying to communicate but getting frustrated. ‘Enough, Peter!’ she said repeatedly in Greek. ‘Enough!’ I didn’t know how to take that; it was as if I was hassling her to do something. I again told her how much I loved her. She remained “nil by mouth” due to swallowing difficulties. The doctors tried but failed to insert a nasogastric tube for nutrition and oral medications.

The elderly Greek ladies in black had quickly marshalled their mystical forces and were assembled by Mum’s bedside. ‘You scared us,’ they said. ‘Who’s going to call us up now and cause trouble?’ Our local Orthodox priest also visited, on his usual round of the wards to visit sick parishioners. Mum received Holy Communion, which seemed to ease her anxiety. She slept more and more, and peacefully.

Read: Book review: Once a Stranger, Zoya Patel

By Thursday, Mum had become unresponsive, her mouth hanging slack. The doctors again took me aside and spoke about withdrawing interventions and making Mum comfortable and moving her to a single room to allow us some privacy. One of the Greek ladies told me, ‘Your mum’s on another path now, I’ve seen this many times, I recognise the signs. She kept saying your name yesterday, over and over. You’re her everything, right to the end.’ I was shaken to my core and broke down to the pastoral care worker.

My phone rang – it was my wife reporting a bad reaction to an anaesthetic for a dental procedure. ‘You better come get me,’ she said groggily. I brought her home and then picked up all the kids from school and daycare; they kept asking about their beloved Yiayia and wanted to see her. I tried to explain what was happening. Only the eldest seemed to understand.

Defying expectations

Returning to the hospital, I was stunned to see Mum responsive – still confused but now demanding and again frustrated, again at me for seemingly being unable to understand her indecipherable requests. But it was a spark, it was life. I sought out the senior doctor who called Mum ‘a bit of a Lazarus’. They kept her in the ward with the other stroke patients – a good sign. I brought in some bouzouki music and headphones, clasping them around her ears. It made her rock her head from side to side in time with the music and raise her left hand in the air as if she were dancing in an endless, dizzying spiral.

The nasogastric tube was successfully inserted on Friday, and a nutritionally-complete, high-energy, fibre-enriched supplement the colour of gruel was attached to the other end. Mum kept telling me how she wanted ‘to go up’ and how ‘everything needed to go up’. It was vague and I didn’t know whether to try and interpret her meaning. I showed the hard-working, tireless nurses a copy of my memoir and told them all about the incredible life that Mum had led. In between her waking cycles, I continued working on the screenplay.

I took Mum’s eldest grandson to see her on the Saturday – her eyes lit up like solar flares when she recognised his face, which made me weep. He spoke to her in simple Greek and she responded as best she could, squeezing his fingers with her only working hand. My son was disappointed the hospital cafeteria was closed, but fascinated by the flapping pigeon that had somehow found its way into the hospital’s main stairwell and told his Yiayia all about it.

On the Sunday afternoon, when I visited with her second grandson, Mum’s mood had changed again. The nurse explained that Mum was now ‘very cranky with us today and says she’s had enough. I can see why but we still have a duty to look after her’. Mum was upset with me too, repeating her sentiments and looking away whenever I made eye contact. I tried to not react and told her the only person she should be complaining to was the man upstairs. She didn’t want to listen to the live broadcast of Sunday church service from Athens via the Greek national broadcaster, ERT.

Mum’s always been stoic but never had any patience for new challenges. She soon calmed down and said she wanted food, ice-cream and yogurt, and winked cheekily at her grandson who smiled. ‘We all love you very much,’ I told her. ‘And I love you, too,’ she replied. ‘Now go.’

Over the next few weeks, Mum’s mood varied from day to day, but she showed overall signs of improvement, starting to eat some solid foods like yogurt and jelly, and able to sit upright without assistance. The physiotherapist and speech pathologist were amazed, and so was I. Mum revelled whenever her grandsons visited. Positive signs, but still a long road ahead.

Read: Book review: God Forgets About the Poor, Peter Polites

Will Mum ever get to see her life on screen? I’d love her to, but right now, I don’t honestly know. No one does. But her life will always be celebrated through her family, every time her grandsons speak Greek or eat ice-cream or marmalade toast. And they’ll soon know all their Yiayia did when they read the book of her life. ‘You have no idea,’ I tell them. ‘But you’ll see.’

ArtsHub reviewed Peter Papathanasiou’s memoir, Little One (Allen & Unwin) in 2020, The Stoning (Transit Lounge) in 2021 and The Invisible (Hatchette) earlier this year.