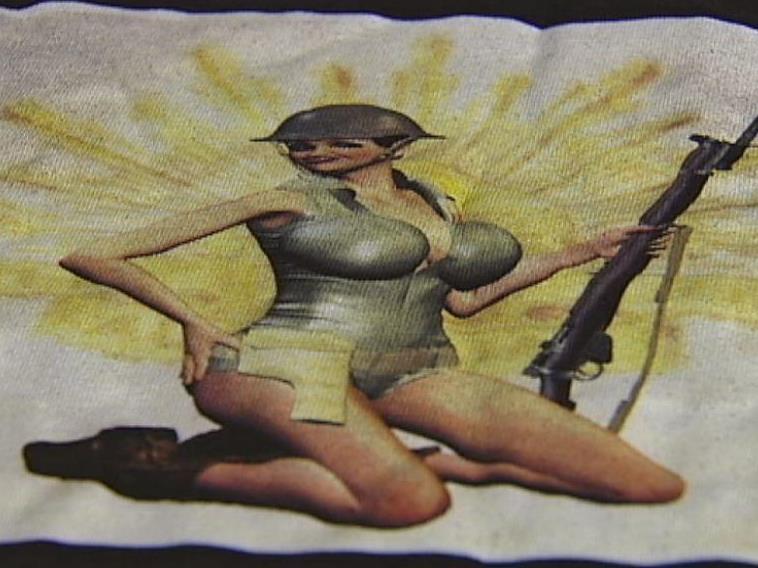

A t-shirt design among Anzac Centenary merchandise was soon removed from stores after several complaints. Image source: www.abc.net.au

When it comes to commemorating the Anzac Centenary, there is plenty of scope for putting your foot in it. From a supermarket’s tacky slogan to a not-for-profit’s sanitised history, the need for skill, sensitivity and creativity has never been more obvious.

The Anzac Day bandwagon is trundling through the arts too, with no shortage of arts events, exhibitions, installations and projects to commemorate the service and sacrifice of Australians in all wars. Indeed Anzac has hijacked arts grants, perhaps to the detriment of sustainable arts funding.

But the skill with which our arts organisations are mobilising in the war effort, makes it clear how important the sector is in creating meaning for a society, whether in reflecting history or in debating it.

What commerce does wrong…

The most egregious Anzac Day clanger (so far) was ‘Fresh in our Memories’, a short-sighted attempt by Woolworths to jump on the Gallipoli bandwagon that quickly turned sour when social media users began ridiculing the brand for exploiting war memory.

Woolworths #freshinourmemories Twitter hashtag was soon hijacked to aptly draw our attention to the bleakness of war, as well as moments of Australian history that are often overshadowed.

— jennifer mills (@millsjenjen) April 14, 2015

— Brett Adlington (@AdlingtonBrett) April 15, 2015

— ABC News Intern (@ABCnewsIntern) April 14, 2015

But Woolworths was not alone. From stubby holders to t-shirts, it seems some retailers are stocking Anzac merchandise in the same way they do Valentine’s Day or Easter. A particularly offensive example of exploitation is the t-shirt pictured above that depicts an Anzac poster-girl kneeling in khaki latex as she holds a gun with one hand and places the other on her butt cheek. The t-shirt was removed from shelves after several complaints.

…and not-for-profits do clumsily…

Even when the direct profit motive is removed, the clangers in marketing are cringe-worthy and the brand-building loud in its silence about the real nature of war.

The Camp Gallipoli website describes the occasion as an opportunity to camp out under the stars ‘as the original Anzacs did’. Educating young people about history and what it means to respectfully remember and pay tribute to the sacrifices of the generations before them is undoubtedly important. But how does ‘eating great tucker,’ and ‘watching historic footage on huge screens’ authentically reflect what the Anzacs felt in the trenches under fire 100 years ago? Camp Gallipoli’s suggestion that claim that sleeping in swags for a night will ‘in itself create history’ turns the centenary into a carnival.

Target has also jumped on board, donating all profits from the sale of exclusive merchandise ranging from swags to scented candles to the Camp Gallipoli Foundation. But just as Woolworths’s claim that #freshinourminds was not a marketing move raised eyebrows, Target’s Anzac charitable range is a transparent call out to customers in the expectation that they will not go home with only a scented candle.

Now in it’s sixth year, despite being one of the biggest contributors to veteran’s welfare, the Victoria Bitter ‘Raise A Glass’ campaign has also garnered criticism. Dr Carolyn Holbrook told the ABC, ‘It’s a brand, an alcohol brand playing on our emotions about the tragedy of these men losing their lives in order to make profits and I find that distasteful.’

…that the arts does right

With $4 million spent on arts through the Australian Government’s ANZAC Centenary Arts and Culture Fund Public Grants Program, there is no argument that the arts is also part of the focus – some might say hysteria – around this anniversary. And when arts funding is being cut, it’s fair to assume that arts organisations may strategically develop projects that are more likely to gain funding.

But the arts offer something much more valuable than khaki swags or portraying war veterans as stubby-holding heroes. In the commercial commemoration, we are not exposed to the malnourishment, the conflict, and the darkness of war. The arts, however, connect with the real stories, and shine a spotlight on the vulnerabilities of soldiers and families.

We are not being subjected to a barrage of triumphalist music or heroic portraits but to a huge range of exhibitions and performances focusing on issues such as memory, loss, destruction and trauma.

Monash University Museum of Art’s second iteration of the exhibition Concrete, for example, demonstrates the ability for art to unite and allows space for contemplation on the most difficult elements of our individual lives and world.

Similarly, Queensland Music Festival’s free concert series One Hundred and One Years (1914 to 2015) spotlights the young recruits not as cardboard heroes but as individuals. The QMF worked closely with State Library of Queensland to gather letters, diary entries, pictures and stories from soldiers in Australia and Germany to share untold stories and educate audiences. To reflect on how young these young men and women were, the open-air concerts will put the spotlight on young actors and musicians.

By stripping away glorification through retelling and remembering a diversity of stories, the arts simultaneously challenges and comforts, and ultimately expands our view of the world. The arts enable us to dissect, engage and remember moments in history in a way that a VB stubbie can or a $250 swag never will.