It was a fiery hot Brisbane day in February 2014, so hot that when I got out of the car, the bitumen under my feet was slightly soft and my sneakers left an indent on the road. A week before, the city had been blanketed in bushfire smoke blowing over from Minjerribah and total fire ban warnings, and the scrub was so dry that the slightest spark could set the bushland anywhere around the city alight. I’m with a friend from Toronto, Canada, where she’s been experiencing blizzards, snow and freezing rain, and had arrived in Brisbane to 41-degree days, blazing sun and the constant threat of bushfires.

It’s not far from the car park to the summit lookout on Brisbane’s Mount Coot-tha, but we walked slowly along the pathway. I chatted to my friend about how silly it was that I’d brought her here. ‘I’m turning into my dad,’ I said. And then a group of pre-teen boys huddled just off the pathway caught my attention. There were four of them, all crouched around a small pile of leaves, one of them furiously rubbing a stick between his hands. My insides immediately clenched up. Four young fullas, some Blak, some (probably) white were mucking around starting fires.

My friend and I went up the lookout and took our photos, and I pointed out Brisbane landmarks to her. By the time we made the slow walk back to the car, the kids were gone, their attempts at a fire thwarted. But as I drove back down the mountain, I saw signs everywhere advising that the barbecues in picnic areas were closed, and the charred bushland where the council had done controlled burns in an attempt to protect nearby homes from any fires, and my brain started whirring.

Intergenerational trauma, severance from Country and Indigenous kids

Around the time of the visit to the mountain, I’d been looking for a way to expand a short story that I wrote, about a boy who throws rocks at a bus window, into a novel. Seeing those kids triggered a series of questions and led me to make the character’s crime lighting a fire instead. What would happen to those kids if they got caught, I wondered? How would the white kids be treated in comparison to the Blak ones? Why would an Aboriginal kid be drawn to doing something that could potentially be so catastrophic for Country?

Read: First Nations storytelling for younger audiences

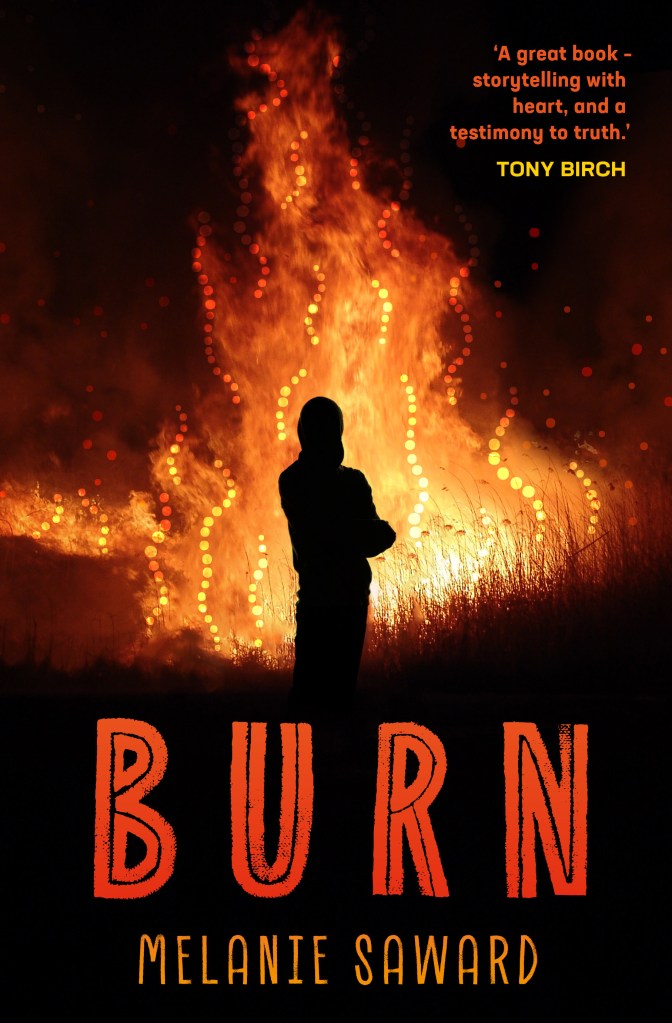

Burn became my attempt at answering these questions. It takes a deep dive into the family and mind of an Aboriginal child who has set several massive fires. Arson is often boiled down to careless, destructive teenagers or firebugs, but in Andrew’s case, he’s not a fully-fledged pyromaniac and he’s not simply a destructive teenager. His fires are a cry for help and attention, and a physical manifestation of what happens when culture is taken away from previous generations.

Without giving Andrew’s story away, Burn is ultimately a hopeful book. But I want to make it very clear that many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people are suffering the effects of intergenerational trauma and getting into trouble, acting out, trying to survive and being locked up, bullied, tortured and having their lives taken away before they’ve even started. In Queensland, where I live, where those kids who were mucking around with fire live, we have the toughest youth crime legislation, laws that human rights advocates have warned are ‘ineffective and will result in more children incarcerated’ despite the fact that evidence-based early intervention, diversion and rehabilitation are more effective ways of building safer communities.

These issues are complex and I don’t claim to have all the answers (for that I look to those doing the work like Wadi Wadi Elder Aunty Barbara Nicholson), but I know that for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kids, connection to our Elders, our Countries and our cultures is vital. If our parents, and our parents’ parents didn’t have that connection to pass on, then how can we expect the next generation not to carry hurt, anger and trauma that they don’t know what to do with? If kids continue to be locked away, the cycle doesn’t get broken. But if so-called justice is handed back to Elders, then it feels to me like the long work of healing can finally begin.

What I hope people will take away from Burn is a new perspective: an understanding of why good kids might do bad things and an understanding that prison is no place for a child.

Burn by Melanie Saward (Affirm Press) is out now.