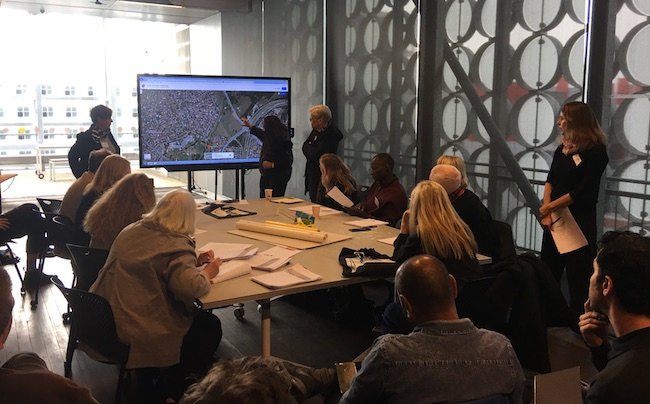

RMIT Students and architects with forum delegates and participants: Annie E. Coombes, Emma Nicolson, Ruth Langford, Julie Gough, Emma Hope, Jo Mair, after workshopping the proposed Truth and Reconciliation Park, for the redevelopment of Macquarie Point in Hobart. RMIT Design Hub, 29 June 2018. Photo Brook Andrew.

The public conversation “Walking on Bones, Empowering Memory” was held at the State Library of Victoria on 26 June 2018 as part of the RR.Memorial Forum, which took place in Melbourne between 25-30 June 2018. Convened by Brook Andrew, the conversation included four panellists: Nelson Abiti from the Ugandan National Museum, Savina Sirik from the Document Center of Cambodia, and Indigenous academics, Professor Marcia Langton and Dr Lyndon Ormond-Parker, from the University of Melbourne.

This event and associated forum are part of a larger ongoing research project, Representation, Remembrance and the Memorial, that Brook has been leading since the beginning of 2016. This research project was awarded a three-year grant from the Australian Research Council Indigenous Discovery program (2016-2018) and is based at Monash University’s Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture.

A recent opinion piece in ArtsHub entitled The spectacle of Aboriginal Frontier War memorial research by Fiona Foley has drawn public attention to the State Library panel, and whilst we are pleased that the event has generated discussion, we are concerned by some comments made in the opinion piece. We write here to provide a fuller picture of these events and research in order to honour the delegates who so generously shared their perspectives, and difficult stories of loss and resilience during the forum.

The aim of the panel conversation and larger forum was to bring into view possibilities for future memorialisation of the Frontier Wars in Australia by learning from Elders, artists, architects, scholars and other experts, both locally and internationally, who are engaged in memorial research and projects.

The forum investigated emerging forms of healing, respectful ceremonial practices and new ways of memorialising traumatic histories and living with hope in the aftermath. 35 local and international delegates and presenters participated in the forum, including those involved in the State Library event. We would like to thank N’arweet Carolyn Briggs, Boon Wurrung senior elder and traditional custodian of the Melbourne region, for welcoming the delegates to Melbourne and helping us to plan the forum events.

The panel conversation was a taste of this research and not a comprehensive overview of the entire forum.

It was designed to reflect on what actions communities are taking towards reconciliation, the role of education, and the need to care for human remains. It sought to draw out common principles between memorial work in Australia, Uganda and Cambodia.

Even though the forum was ambitious, this gathering could not encompass the immensity of this topic, and include the many peoples who join internationally to confront these issues within their own communities, and with governments and bodies like the United Nations. The forum did not purport to provide a history of memorial activity around the Frontier Wars in Australia, or survey artworks that do this work, nor present all the current research into massacre histories; it was an investigation of select case studies from across Australia compared against international examples.

One of the aims of the research is to gather and test existing principles that guide people from different backgrounds and disciplines to work together including artists, Elders, communities, architects, corporations and government bodies.

In another of the forum events, we workshopped three case studies that are proposed memorials for Australia. We referred to the Australian Indigenous Design Charter, and heard from one of its authors Dr Brian Martin, as well as insights from the international delegates present. Otto Braided Hair, a Northern Cheyenne representative, who has worked to secure the Sandcreek Massacre National Historic Site in the United States for over twenty years, articulated the need to take time in these processes which require respectful and careful listening and response, and space for multiple voices.

At the State Library panel conversation, Marcia Langton shared research from her book Welcome to Country and related her own family history of massacre, where the remains of her ancestors are still scattered without proper burial. She called for an education textbook similar to that developed in Cambodia for high school students that explains the genocide committed under the Khmer Rouge period from a grassroots perspective. Savina Sirik further spoke of the memorial work in Cambodia and how human remains have been housed in village stupas, as well as the more well-known killing fields which have become international tourist destinations.

Nelson Abiti described post-conflict activities in northern Uganda aimed at reconciling children who were abducted, indoctrinated and trained to become soldiers who kill their own families. He spoke of the importance of healing rituals that draw on cultural processes. This was a theme also picked up by Lyndon Ormond-Parker in his discussion of the proposed National Resting Place for unprovenanced Aboriginal human remains – thousands of which are currently stored in a warehouse in Mitchell, ACT.

Similar to the proposed Sleuk Rith Insitute in Cambodia, the National Resting Place will be a multi-purpose complex serving ceremonial, educational and archival functions. A 2014 consultation report for the National Resting Place specifies Canberra as the best location for this multi-purpose complex. As Lyndon Ormond-Parker and Neil Carter, one of the authors of the report, informed us in an interview conducted for this project, the design for such a complex is likely to be selected from an international architectural competition, but orchestrated by an Indigenous-led panel.

Since the 1970s many historians and activists have been working to break the ‘Great Australian Silence’ and of particular note is the Aboriginal Memorial (1988) at the National Gallery of Australia, that was curated by Djon Mundine and made by the Ramingining artists of Central Arnhem Land. From the outset of the project, these important predecessors have been acknowledged in the literature review, on the project website, and in publications.

Though it was not the main focus of the evening at the State Library, Brook did reflect on the role of artists and artworks as memorial including acknowledging the important contribution by artists who were present: Judy Watson, Fiona Foley, Jonathon Jones and Julie Gough.

Corina Marino, Jenny Bisset and Anne Loxley presenting the Blacktown Native Institution site to workshop participants. RMIT Design Hub, 29 June 2018. Photograph by Brook Andrew.

In other forum events, including the public program at the National Gallery of Victoria on the 30 June, further research and efforts from across Australia to bring visibility to the history of the Frontier Wars and the continuing legacies were presented. This included Aunty Sue Blacklock from the Myall Creek Massacre Memorial committee, Darug Traditional Owner Corina Marino who is working on projects at the site of the former Blacktown Native Institution with the Blacktown Arts Centre and C3 West program, historian Professor Lyndall Ryan who has developed an online massacre map, musician Jessie Lloyd who is leading the Mission Songs project, Dr Greg Lehman, a Palawa (Tasmania) scholar who works to secure memory of the old people, architect Carroll Go-Sam who is affiliated with the Aboriginal Environments Research Centre at the University of Queensland as well as a number of artist presentations. We also thank the Elders who welcomed a small group of our delegates to putalina (Oyster Cove, Tasmania) in the days following the forum for a smoking ceremony that brought peace after a week of intense discussions.

The afterthoughts of the State Library discussion highlights both the importance and the challenges of walking in this difficult territory, especially when many have connections to and ownership of these traumatic experiences that still exist within our memory today.

It was concluded in the forum that these confrontations and oppositions can point to where future work needs to be done. As we wrote in a chapter for the 2018 book Remembering the Myall Creek Massacre: “for decades, many people including artists, historians, activists and community leaders, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, have been knee-deep in the business of accounting for and remembering the Frontier Wars and the facts of Indigenous sovereignty, but the general Australian population remains reluctant.”

We agree that a lot more research and action is required. We strongly believe that the more projects, voices and dialogues, the better. We encourage others to continue this work as many have done for decades.

For more information about the project, visit www.rr.memorial

An exhibition related to the research project and including artworks by Shiraz Bayjoo, Judy Watson, Julie Gough and Roberta Rich and research material, is on view until 4 August at the MADA Gallery, Monash University, Caulfield.

To support the goal of the Myall Creek Memorial committee to build a permanent cultural and education centre adjacent to the site, visit www.myallcreek.org