Image source: parade.condenast.com

If my Facebook feed is anything to go by, last month parents scrabbled to make costumes of popular characters from children’s books. They were preparing for the Children’s Book Council of Australia’s annual reading extravaganza, Book Week, a series of events across Australia designed to get kids reading.

Book Week shows that we are keen to encourage kids to read, and demonstrates the value of talking about books to promote reading. What’s less often acknowledged is that reading socially can be beneficial for adults too, although the politics are in some ways more complicated.

Reading books on your own improves empathy and theory of mind, the ability to understand that others might think or behave differently to you. Fiction shows characters’ thoughts – and how those thoughts drive or are hidden by characters’ words and actions.

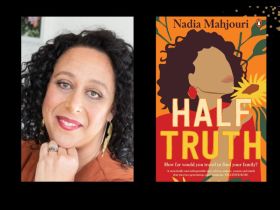

With the popularity of Oprah’s Book Club and, more recently, Jennifer Byrne’s The First Tuesday Book Club, it’s clear that many adults enjoy connecting with each other over novels. I helped run a book club in Brisbane for more than two years and there’s a growing body of research on the value of social reading.

Social reading in book clubs is valuable because readers can make sense of big ideas through personal experience. Book clubs invite readers to connect the themes of books – ideas such as racism, gender, nationhood and representations of the past – by linking the characters’ experiences to their own. I noticed how books such as Andrew McGahan’s Underground invited readers to discuss, from their own personal experience, the impact of corporations on government in Australia, and how Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber prompted discussion about the ways fairytales shape readers’ thoughts about their own sexualities.

Novels invite this kind of discussion because they explore wider ideas through characters’ inner lives.

It’s true that book club discussions of what book to read next may be influenced by the tastes and attitudes promoted on TV and do not necessarily promote access to a diverse range of titles, and researchers point out that these celebrity book clubs are not necessarily empowering for readers.

Publishers have picked up on the selling power of book clubs. Random House, for example, runs a Book of the Month Club, suggesting novels for book clubs and offering a set of questions. Many publishers provide free questions with selected books, directing readers not only to what texts are worthy of discussion but also how to make sense of them.

Universities and schools also play a role in identifying “valuable” books by introducing readers to books considered beneficial or worthy of study, as researchers show. Those forces make social reading subject to power struggles by shaping what book clubs choose to read and, by extension, what books are considered valuable. For example, book clubs could easily end up reinforcing dominant ideas about the divide between literature and genre.

But they also allow readers to talk about these very divides and create a more personal sense of what makes a good or valuable book.

Research in the UK suggests that most book clubs meet in people’s home, making them more private than public. While the tastes of celebrities and publishers may influence readers in the home environment, the grassroots nature of these book clubs offers a space to resist these forces. Simply asking each other questions such as “did you like the book?” and “why?” allows readers to challenge accepted ideas of literary value.

Because books are about people’s lives, and because the social setting of the book club creates a space for the discussion of personal experience, social reading fosters thinking about the personal as an example of the big picture. In responding to others’ interpretations and experiences, discussion also becomes an opportunity to reconsider life narratives from a different point of view, to reinforce or challenge beliefs unconsciously or consciously held. In linking the personal with wider issues, readers discussing books actively work to represent themselves to others.

It’s easy to dismiss book clubs as, at worst, frivolous or pretentious or, at best, only having an impact on a personal level. But book clubs’ social and personal qualities are actually their main strengths – they allow readers to link the personal with the political.![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.