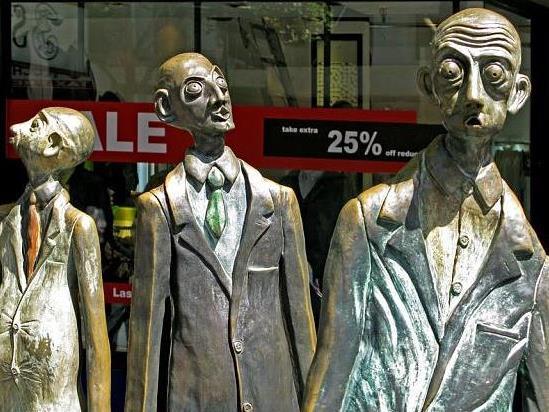

Alison Weaver and Paul Quinn, Three Businessmen Who Brought Their Own Lunch, Image via Urban Melbourne

When you come across a tiny mobile phone or pair of workers’ gloves sculpted in concrete and installed in a shadowy corner of a street where you least expect them, you are probably encountering an artist’s gesture to enliven the city. In the face of inadequate city planning, our sights often turn to artists to provide vitality and excitement in public spaces. Not that they are able to cure the problems of lack of co-ordinated decision making, increasingly mad traffic congestion, grimly opportunistic building developments and gross dereliction of responsibility in the provision of adequate public facilities. But within the limits of what is allowed under the weight of regulation, artists are helping us to better enjoy the potentialities of public space for people.

Almost all our metropolitan governments and some other local authorities have made gestures towards encouraging public art commissioning and allowing for the realisation of performative ideas which enliven the experience of the denizens of the city and animate otherwise drab environments. Some of the more enlightened councils like the City of Sydney have actually devised a coherent cultural plan for the city, which provides a complex of diverse opportunities for artists to be the catalysts for positive community experiences. These can be huge like festivals that take over a whole city or tiny like those discrete mini sculptures.

But artists and designers have so much more to offer than being brought in at the end of a process to provide a cosmetic fix for otherwise failed built environments. Artists who have been commissioned to participate in the whole process of designing public spaces can have truly thrilling innovative ideas. By being integrated into the design team at an early stage, artists can bring their capacity for lateral thinking to surprize the other people involved in the process who may find themselves constipated by convention and long standing entrenched patterns of thinking.

In the visual arts, problems most often arise in the process of commissioning public art projects. Too often it is a token gesture when all the decisions have been made and the spaces already built. Local government officers often have little understanding of the potential contribution that artists can make and the way they work. Usually they simply put out a call for expressions of interest (EOI) for an art object to be installed in a public space (now derisively known as ‘plonk art’). And worse, they may expect artists to provide a well developed concept response to complex issues and mountains of documentation without having the opportunity to explore the site and its surroundings, discuss it with the council officers and consult the community. This can lead to insensitive proposals which have no relationship with either the place or its people. It also is asking artists who are some of the lowest paid people in the community to meet the cost of preparing detailed proposals which may have a small statistical likelihood of success in a very competitive environment.

What is either not known or ignored is that the art industry has standards that provide clear guidelines for best practice. Two stand out documents are: the Code of Practice for the Professional Australian Visual Arts, Craft and Design Sector https://visualarts.net.au/code-of-practice/ ; and ‘Public Art: making it happen’, a very sensible and authoritative set of guidelines for local councils, commissioned by the Government of South Australia through Arts SA, and available from them for free.

We certainly need creative people to enhance our experience of cities which are growing exponentially in ways that we find hard to love. Anyone who has ever joined a residents’ action group to try to achieve a good design outcome for development in their neighbourhood will probably have been bruised by the experience of challenging developer greed and the lack of will by councils or state governments to stand by their own regulatory principles in the face of the power and pressure brought to bear by big money. Good design seems quickly to drop out of the equation. But the involvement of people who are skilled at ‘design thinking’ as part of the process of dealing with complex problems could lead to much better solutions. People with imagination – artists and designers – should be at the front line in solving the ‘wicked problems’ of the design of our places and spaces, but instead are often brought in to try to clean up the mess when it’s all too late.