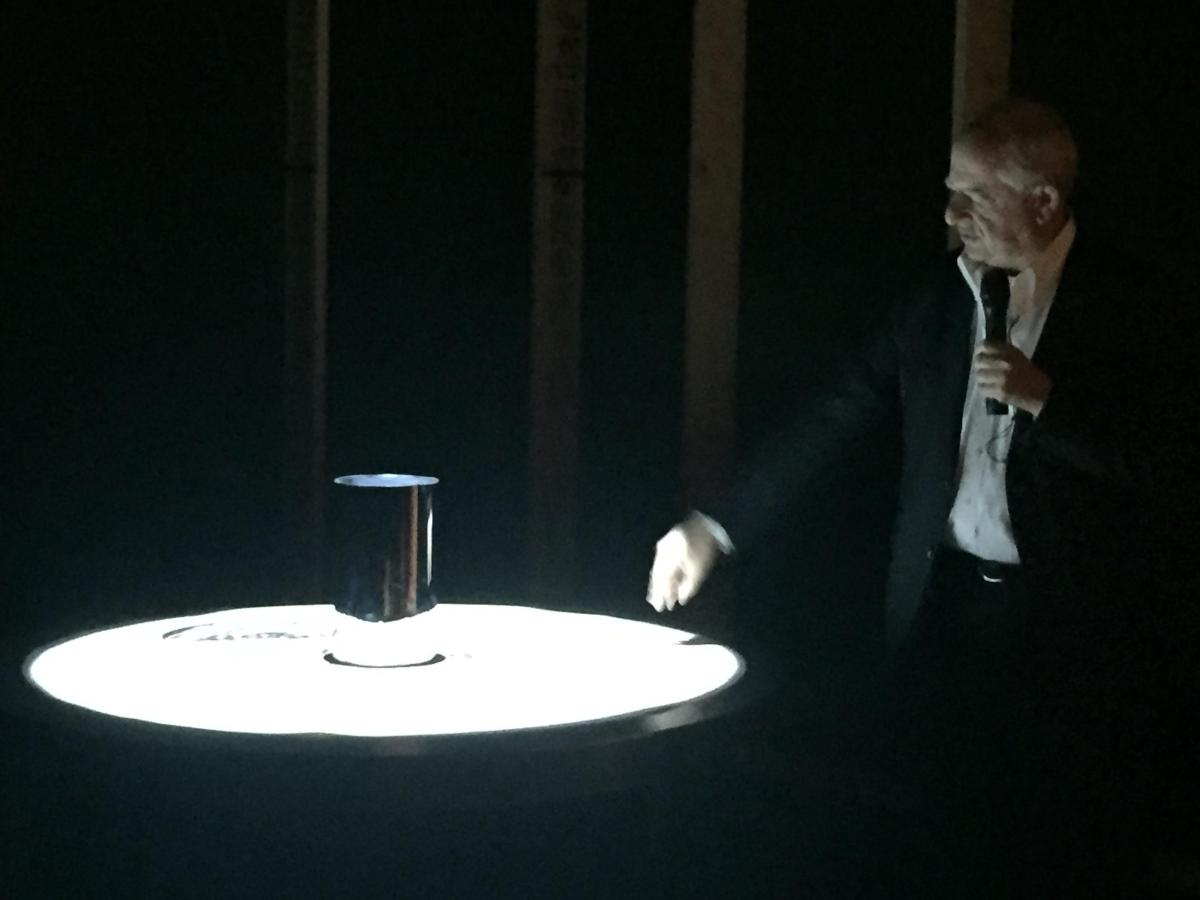

William Kentridge; image Artshub

Acclaimed South African artist William Kentridge was recently in Sydney for the opening of his exhibition, That which we do not remember, at the Art Gallery of NSW (8 September 2018 – 3 February 2019).

ArtsHub caught up with the celebrated artist, who shared some wisdoms for artists and creatives when it comes to facing the reality of the studio.

Embracing stupidity in the studio

‘One never appreciates quite the degree for need of stupidity in the studio,’ said Williiam Kentridge. ‘I am a great believer that stupidity gives the work its impulse, the benefit of the doubt.’

It is not far off Oscar Wilde’s great quote: ‘Experience is simply the name we give our mistakes.’

Kentridge believes that the degree to which thought is rescued by the work – rather than the work being a display of planned gestures – will always lead to a better work.

Avoiding the pressure of grand ideas

In 2016 William Kentridge opened The Centre for the Less Good Idea, an interdisciplinary art incubator that encourages collaboration. He said the name for the centre came from an African proverb: “If the good doctor can’t cure you, find the less good doctor.”

‘It’s about the idea that when grand ideas no longer work – especially when you think of the calamity of so many huge ideas of the world – it is the things in the margins, in the peripheries, that can actually show us different routes,’ explained Kentridge.

He continued of the centre’s philosophy – which could be applied to making in general: ‘It is about people who normally haven’t worked together, and it is about finding the energy and the new ideas that come from working outside of yourself. It encourages the short form (in making work) … and people don’t have to write a proposal or set out their idea in advance – time allows the work to happen.’

Don’t always aim for perfection

In a lot of Kentridge’s drawn animations, the process of erasing is embraced.

He said: ‘When I started doing animation, I tried to do perfect erasures, so that you couldn’t see the mess I left behind between frames. Then I came to realise that it was the trace that was the interesting thing that I did – it was a bit of a relief to take away the responsible, to get the perfect slide.

‘We arrive at these realisations in our work from experiences, rather than on principle or intention, said Kentridge.

Installation view Kentridge’s Drawing for 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès, Day for Night and Journey to the Moon (2003) at AGNSW; photo ArtsHub

Let the medium lead you

One of the great lessons Kentridge says he has learnt is to rely on the paper to lead you.

He spoke of working on the opera Lulu, and rather than sketching up concept drawings, allowed a consolidation or accumulation of sheets of paper to build as a way of drawing.

‘When you are working with charcoal you can edit with an eraser; if you are using Indian ink then you have to rearrange or change the sheets of paper. The face could be slightly shifted in different positions or angles. What that does is say that the image is provisional and unstable,’ explained Kentridge.

Embrace peripheral thinking

Kentridge has said that his work starts with images that interest him or provoke him.

‘The preamble to the work itself – it is a physical thing – is about literally walking around the studio before the work starts for the day. Sometimes it’s for an hour, sometimes ten minutes. It is about allowing the activity of walking to begin the thinking.

‘In the studio you have all these different objects – postcards newspaper photostats the drawing you were working on yesterday, the drawing you are hoping to work on today – so the circuit around the studio, and the peripheral vision you have of all these different things is a kind of peripheral thinking; it is like a gathering of the energy.

‘And then there comes the moment when you commit yourself to the drawing and the world is reconstructed from the fragments around the studio. Its understanding the studio as an expansion of one’s head,’ he said.

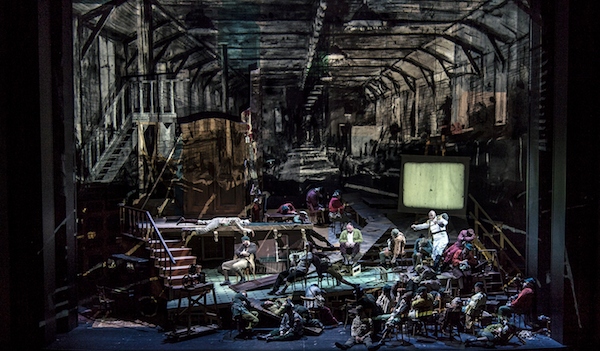

Kentridge’s opera production of Wozzeck as performed at Salzburg Festival 2017 – to come to Sydney in January 2019; photo Ruth Waltz

Embrace the bastardry of mixing traditions

‘When I was a student I was both drawing and working in a theatre company and acting. The good advice I got from many people was, “For god’s sake choose what you are going to do!”

‘At a certain point I decided I would no longer be an artist. I would be an actor, and after three weeks I failed. So then I decided to be a filmmaker and that was a disaster too. And after some years, I found I was back in the studio making drawings again and then found that I was filming those drawings, which became a kind of animation. It took a while for me to understand that the only hope for each niche practice was what they each got from outside themselves,’ he continued.

‘That is, the drawings were much more interesting if they were not done as a drawing, but as applied drawings in the service of a piece of theatre or an animated film. Even to be rubbed out they became much more interesting as drawings. So my inclination was to ignore that early advice and to work against that,’ Kentridge concluded.

That blurring has become signature to Kentridge’s practice which today bridges theatre, opera, film, performance, sculpture, drawing and many more.

‘The cumulative does give a sense of excess of making – it relies on different ideas from different eras, music from different places – and comes together as a polemic for bastardry for the mixing of traditions – the understanding and misunderstanding of each other,’ added Kentridge.

Be biopic

Kentridge observed of the process of drawing or making, which he says is not exclusive to artists: ‘It is the difference between what it is to be drawing – that is the distance of yourself from the paper and that very myopic view of what you are doing – and the moment you turn around and see the drawing afresh from a distance.

‘What happens is a complete bifurcation of the artist: You have one person – the artist as maker – and then you have the other, standing over there looking at the mess at what that person is doing and the stupidity is completely obvious. So you give instruction to the other self and step back in. The one at the coalface is always a disappointment to the other.’

Kentridge believes that it is essential to ‘stalk’ your drawing and then bifurcate.

Kentridge worked with designer Sabine Theunissen to create a bespoke narrative across the AGNSW’s exhibition. Photo: ArtsHub

Step back and say no

What makes Kentridge’s exhibition at the AGNSW a little different than other big-name shows, is that he curated the exhibition himself – not just a “that goes there”, but the whole theatrical presentation, complete with floating scrims, blackened Portuguese cork-walled video ”huts”, staged wicker chairs and a “recreation” of his studio.

But it hasn’t always been that way. He spoke of an early career show at the iconic Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York.

‘I was struggling with the technicians – how it looked; it wasn’t how I expected – and I could feel myself getting more and more bad tempered. It was the first time that I did a project at MoMA, they had a bad projection [equipment],’ said Kentridge.

‘I had to take a step back and say, “NO William … you have to think of this not in the moment but say to your 18-year-old self it’s fine because in 23 years you will have the film on the walls of this museum”.

He was right. This exhibition at the AGNSW Kentridge has had full and complete control of how the work has been presented.

Read: Review William Kentridge at AGNSW

Listen to the pauses – embrace the gaps

The gaps between where you should be making connections between things but where they refuse to find the connection – the gap itself – I have come to learn to embrace,’ said Kentridge.

‘It is the activity we do when we can’t find the connection – the incoherence.’ He spoke of the title work of the AGNSW exhibition, That which we do not remember, which came from a “gap” in a 5-meter frieze Kentridge had made along the Tiber River (Italy).

‘I did the geometry or geography wrong and we had a section left – a black square. Rather than try to decide what figure should fit in this lineage and history I decided to leave as a black square,’ adding that only afterwards did he reach the connection with Malevich’s Black square.

One of the great works of art that has inspired William Kentridge is Malevich’s Black square (c1932). Coincidently, it happens to be on display on loan from The Hermitage Museum upstairs in the gallery from Kentridge’s exhibition at AGNSW.

In the same way Malevich’s work and Kentridge’s frieze offered a powerful pause, Kentridge also use the example of words to deliver his point.

Typed they read one way, but in terms of a lecture those words also become about the pauses and the gestures. He uses this thinking to help understand the greatest limitation in your body when making – the movement between the physical object and the movement of thought.

He encourage that we should all allow the gaps to enter, and to embrace them.

William Kentridge’s exhibition, That which we do not remember runs from 8 September – 3 February 2019 at AGNSW.