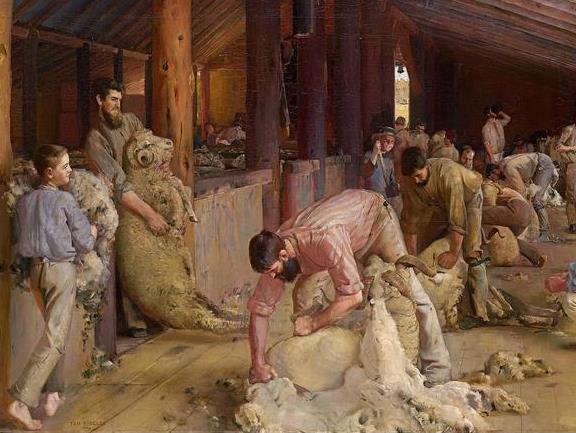

Shearing the rams, Tom Roberts 1888–90. (detail) Courtesy of the NGA.

On December 4, The National Gallery of Australia (NGA) opens its exhibition of Tom Roberts’ work as the centrepiece of a major re-hang of the gallery’s Australian collections, and has flagged the significance of the exhibition in these terms:

This extraordinary exhibition brings together Tom Roberts’ most famous paintings loved by all Australians. Paintings such as Shearing the rams (1888-90) and A break away! (1891) are among the nation’s best known works of art. An exhibition for all Australians, it is not to be missed.

But who does love the work of Tom Roberts? Well, certainly not all Australians. According to the findings of a national survey of Australians’ cultural tastes that I am leading, a Roberts fan probably identifies as middle-class or above, has a bachelors or postgraduate degree, and is overwhelmingly likely to be white.

The survey, part of a project funded by the Australian Research Council, was administered in the first half of 2015 to a nationally representative sample of 1,202 Australians, augmented by boost samples for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, Italian, Lebanese, Chinese, and Indian Australians to bring the overall total to 1,462.

The survey included a broad-ranging set of questions on tastes for a number of Australian and international artists, set alongside questions probing tastes for different kinds of art and art museums. These are accompanied by similar questions exploring tastes for television programs and media personalities, different kinds of music and literature, sporting activities, and heritage pursuits.

The survey’s examination of these cultural tastes and activities forms part of a more wide-ranging inquiry exploring how the social patterns of involvement in both the production and consumption of culture in Australia have changed since the landmark 1994 cultural policy statement Creative Nation.

Considered in this broader context, while Roberts’ paintings unite tastes more strongly than some other Australian painters, most Australians have no knowledge of him, and the tastes of those who have seen and like his work reflect all the familiar divisions of Australian society – age, level of education, social class identification, and ethnicity.

Who’s heard of Tom Roberts?

To start with, around 63% of Australians have never heard of Tom Roberts – or at least, they hadn’t before Radio National’s recent competition to win free tickets to the exhibition. They are much more likely to have heard of Ken Done, Sidney Nolan, Albert Namatjira, and Brett Whiteley than of Roberts.

Women are slightly more likely to have heard of Roberts, at 41% compared to 32% of men. A fondness for his work is more-or-less equally shared among the women and men who have seen it.

Age proves more divisive, ranging from only 13% of those under 25 who have heard of him to 60% of the over-60s. Only 25% of the under-25s who know Roberts like his work, compared with 85% of the over-60s.

Level of education divides Australian tastes for Roberts too. He is little known among those whose education finished with secondary schooling – just 20% – rising to 43% of those with university degrees, and 52% of those with postgraduate qualifications.

Only 29% of those who self-identify as working-class know Roberts, compared with 39% of those who see themselves as middle-class and 48% of those who place themselves in the upper middle classes.

It’s worth noting that most of those who have seen Roberts’ work like it irrespective of their level of education and class identification, although less so for those seeing themselves as working-class.

But if you are a Lebanese, Chinese or Indian Australian, Roberts is unlikely to have registered on your cultural radar. Only 13% of the Chinese Australians in our sample and 11% of Lebanese Australians had heard of Roberts, with just 10% and 7% of those two groups having seen and liked his work.

Only 8% of the Indian Australians surveyed had heard of Roberts, and none had seen or liked his work. However, more Italian Australians have both heard of (26%) and seen and liked Roberts (16%).

A significant percentage of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander sample had heard of Roberts (28%), and 20% had both seen and liked his work.

What does this mean?

Of course, the survey data itself doesn’t explain these different tastes. Our findings fit with broader patterns – in Australia and internationally – of those with higher educational qualifications and social class positions participating more in visual arts.

The relative lack of interest in Roberts evident among the members of the different ethnic groups we surveyed may simply reflect a lack of familiarity with his work on the part of newer denizens of Australia, or a degree of disinterest in an artist who, if he was an iconic painter of Federation, was by the same token a painter of and for White Australia.

As a leading member of the late 19th-century Heidelberg School, Roberts also played a key role in making the bush appealing for white Australians by – controversially – painting Aboriginal people and their culture out of it (though his paintings remain haunted by Aboriginal absence/presence).

That said, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders surveyed greatly prefer Namatjira’s work; who also – incidentally – just pips Roberts in the overall popularity stakes (77.3% vs 76.7%) as the painter who is most liked among those who have seen a particular artist’s work.

There are good reasons for asking whether Roberts is the best choice for celebrating a major re-hang at the NGA. That said, it’s a choice that has a good deal going for it in the respect that, unlike some other iconic Australian artists – Whiteley and Nolan, for example – his work elicits few negative reactions among those who have seen it.

Only a little more than 2% of these registered a dislike for Roberts’ paintings compared with 30% who disliked Done’s work, and the 23% and 11% disliking Whitely and Nolan.

What is less clear is how good a choice Roberts is at a time when our national institutions should be reflecting Australia’s increasing multicultural complexity.

Much will depend on how the exhibition is curated and related to the new arrangement of the Australian collection. Given the significant role the NGA has played in redefining Australian art through its recognition of Indigenous art, there are grounds for optimism here.

For my own part, while Roberts is not my favourite painter, he is an interesting one, and I look forward to seeing what new light the exhibition throws on Roberts’ place in Australian visual culture.

Tom Roberts

National Gallery of Australia

Opens December 4.

Tickets.

This article was first published on The Conversation.