Interior of the State Theatre Centre of WA. Photo by Eva Fernandez.

Recently, the WA Premier launched an Economic Development Framework – Diversify WA with one of the key focus areas being the Creative Industries. The Chamber for Arts and Culture has long argued for the sector to be included in a broader economic framework and our presentation of REMIX Perth over the last three years has promoted this thinking. The hope now is for a meaningful commitment to a long term-strategy that grows the potential of our cultural sector.

The discussion around the need to shift Western Australia from a boom and bust mining economy to one that is more diverse and resilient is not new. But despite decades of well stated intentions, mining grew from 22% of the WA economy in 2007/08 to 31% in 2018/19. With a current overall unemployment rate of 6.8% and youth unemployment at 17%, it is clear this dominance is not healthy for broader economic outcomes – there has been a long-term complacency in growing other areas of the State’s output which is starkly highlighted in times of downturn.

The Creative Industries have been identified as one of the ‘green shoot’ areas of the economy that, if nurtured may grow into robust part of our ecology. Perhaps a more apt analogy may be that the current arts and cultural sector has for too long been given the bonsai treatment with constant trimming keeping it in the ornamental section of the economy.

Jobs, jobs, jobs

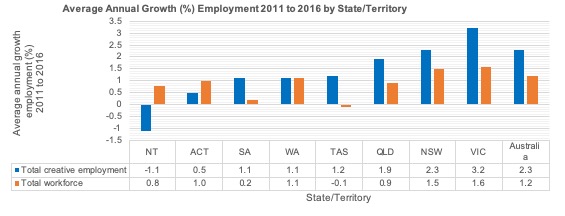

From 2011-2016, creative employment in Australia grew at nearly twice the rate of the Australian workforce and it is highly likely to continue to grow into the future. Creative employment in Australia grew by 2.3%, compared to a 1.2% annual average growth rate for the total workforce.

However, the rate of creative industry employment growth in WA has tracked below the Australian average. In WA, the average annual growth of total creative employment for the same period was 1.1 % – less than half the rate of the national average. WA also had a lower share of creative employment (3.8%) in 2016, than the Australian average (5.6%).

Average annual growth (%) employment 2011 to 2016 for creative employment and total workforce by State/Territory in Australia. Creative employment counts and intensities are derived from Australian Bureau of Statistics Census estimates by Queensland University of Technology’s Digital Media Research Centre. Supplied by WA Department of Local Industries, Sport and Cultural Industries.

What’s the Plan, Stan?

The New South Wales government has recently researched the economic value of arts and culture in the State and released an impressive Cultural Infrastructure Plan, while Victoria’s Creative State Strategy has realised significant investment for the sector. We need similar rigour around research and planning in order to make any significant shift in the West. Clearly there will always be a skew towards the larger cities which attract clusters of cultural industries, but Western Australia can make up for any disadvantage in population size with some smart thinking about the strengths we do have.

What is also important is that such a plan supports the whole ecology of the creative industries rather than cherry-picking the easy wins. The best approaches recognise the interrelationships within creative sectors such as between design and art, between music and film, between theatre and technical expertise, between architecture and literature. We need to create pathways for artists, technicians and producers that allow them to collaborate, create and earn across multiple platforms. The current reality is that many artists in music, performing arts and visual arts earn well below the national mean income and we need to ensure growth translates to a more sustainable career path for them.

Wide Open Road

Space and distance are not necessarily detrimental to our creative output and afford us the opportunity to do things differently. Seeing the world through a Tim Wintonesque squint gives us a unique perspective and there are some obvious and immediate strengths that Western Australia could leverage in a plan:

WA is home to a range of Indigenous cultural experiences from the South coast to the far north. Significant progress such as the 2018 South West Native Title Settlement with the Noongar people (the largest native title settlement in Australian history) lays the ground for the development of tourism, arts and events underpinned by the cultural authority of the First Nations people. With the Australia Council reporting the growth in appetite for cultural tourism, this is a point of distinction globally for WA.

Scheduled to open in late 2020 the new Western Australian Museum will be a gamechanger for the State. From the architecture to world-leading exhibition design and an extensive consultation process, the Museum promises to reflect a respectful and contemporary understanding of the history and culture of Australia’s largest state. It is a chance to give depth and resonance to the experiences of living on this land. But this building needs to connect into a broader cultural infrastructure plan that inspires Western Australians and visitors to explore these stories more widely through other experiences.

WA’s screen and digital economies are humming with ScreenWest more than doubling the value of its contracted productions over the last five years. Rather than the generic blockbuster model, current productions such as Dirt Music, Rams, H is for Happiness and Aussie Gold Hunters epitomise all that is unique about the West.

Looking to some longer-term outcomes, we need to grow a more sophisticated relationship with our Asian neighbourhood. Not only does it represent a dynamic market, but a deeper cultural understanding will support all aspects of our economy from tourism to education and collaborative projects.

Live Performance Australia’s 2018 report showed Western Australia as having the highest per capita spend on arts and culture, and a year on year 30% increase in revenue. It’s an important part of the equation to know that there is an enthusiastic audience for arts and cultural experiences. While events such as FringeWorld Festival (now the third largest in the world) have been key drivers of this, the growth of regional events means this is not restricted to the city.

Whilst the Government’s approach is based purely on an economic rationale, the hope is that there will be a growing recognition of the wider public value of investment in arts and culture. We are looking to our political leadership to demonstrate a real commitment to elevate our cultural identity and, to quote Winton ‘the pace of transformation need not be geological’.