Rosaleen Norton, or ‘The witch of Kings Cross,’ is finally receiving the attention she deserves.

Born in Dunedin in 1917, emigrating with her family to Sydney in 1925, and dying in 1979, Norton was a trailblazing woman and under-appreciated cultural touchstone of 20th century Australia.

A self proclaimed witch, Norton experienced childhood visions. From around the age of 23, she practised trance magic and, later sex magic in various flats and squats in inner-city Sydney.

Trance magic involved Norton meditating (sometimes with the assistance of various substances, ingested and/or inhaled) and raising her consciousness. The aim was to transcend her physical body and conscious mind to experience higher forms of existence.

Sex magic was developed by the infamous occultist, Aleister Crowley around 1904, and involves a complicated series of sexual rituals designed for a variety of perceived needs (depending on the practitioner), including spiritual awakening.

FireBird by Rosaleen Norton. Black Jelly Films, courtesy Burgess Family.

As an artist, Norton drew and painted her beliefs and the gods, goddesses, and spiritual beings who were central to it. She also lived free from societal expectations. Not only a witch, but openly bisexual, Norton robustly challenged a predominantly Christian Australia. But she was reviled for doing so, attacked by the media for her art, her beliefs, her lifestyle, and sometimes, her appearance. She experienced police surveillance and faced obscenity charges over her art.

Read: Sonia Bible and The Witch of Kings Cross

Norton defied cultural norms and, though she did not identify as a feminist, was a powerfully unconventional woman. Poor but not without imaginative style, she had distinctive arched eyebrows, sometimes dressed in male attire, and was often photographed wearing all black. With a new film about her life being released next week, it is timely to look at her legacy.

Freedom and creativity

Norton’s story has fascinated me from the age of five, when I began to devour the 1970s tabloid newspapers and magazines that featured her. During those years, Norton had become something of a recluse, rarely appearing in public but graciously agreeing to be interviewed about her life. By this time, the legend of ‘the witch of Kings Cross’ was entrenched. Norton was not averse to it, even donning a pointed hat for photos.

This passionate interest went on to inform my adult life. As a classicist, I have explored Norton’s occult belief system, which embraced the old gods. Beings such as Hecate, an ancient Greek goddess who presided over witches, Lilith, the ancient female demon originating in Mesopotamia, and the Egyptian goddess Isis, were at the heart of Norton’s magical practice.

Pan and Daphnis. Roman copy of Greek original c. 100 BC, found in Pompeii. Wikimedia Commons.

But the Greek god Pan was at the centre of her pantheon. To the ancient Greeks, Pan was the god of nature, regularly associated with pastureland and its human and animal inhabitants.

Half-man, half-goat, Pan also embodied the sexual drive, the uninhibited urge to copulate. As the ‘High Priestess at the Altar of Pan’, Norton performed rituals both alone and with members of her inner magical circle in his honour.

In my own research, I have studied witchcraft through the ages and how, especially from Victorian times, it provided an outlet for unconventional women to leverage freedom (and sometimes power) and express their creativity. (Even as a child, I baulked at the media’s determination to cast Norton as a woman to be judged, feared or, worse still, mocked.)

Read: Exhibition Review: NGV Triennial, NGV International

As an academic, I extended my research into the worlds of Greece and Rome with a focus on sexual histories and belief systems – and explored Norton’s life through the same lens. Along the way, I acquired enough material to donate a personal archive on Norton to the library at The University of Newcastle.

Norton’s identity as a witch was formed early. As a child, she was drawn to the night, to nature, and to drawing and recording the preternatural world. In an article published in Australasian Post in January 1957, she describes visions from the age of five (a lady in a grey dress, a dragon) and trance states (which she called ‘Big Things and Little Things’) to capture the experience of her body growing in size as she ‘floated’, as if in a dream. She also records the appearance of ‘witch marks’ on her left knee when she was seven (in the form of two small, blue dots).

Bored and frustrated by her middle-class life in Lindfield on the North Shore, Norton left home for inner-city Sydney at the age of 17 and never returned. She found employment as an artist model (including a stint modelling for Norman Lindsay), a pavement artist, and as a contributor to the avant-garde publication, Pertinent.

Eventually, she based herself in Kings Cross. There, she was free to explore and develop her beliefs and practices. In the late 1940s, it was where she met one of her companions in life and magic, the poet Gavin Greenlees (1930-1983).

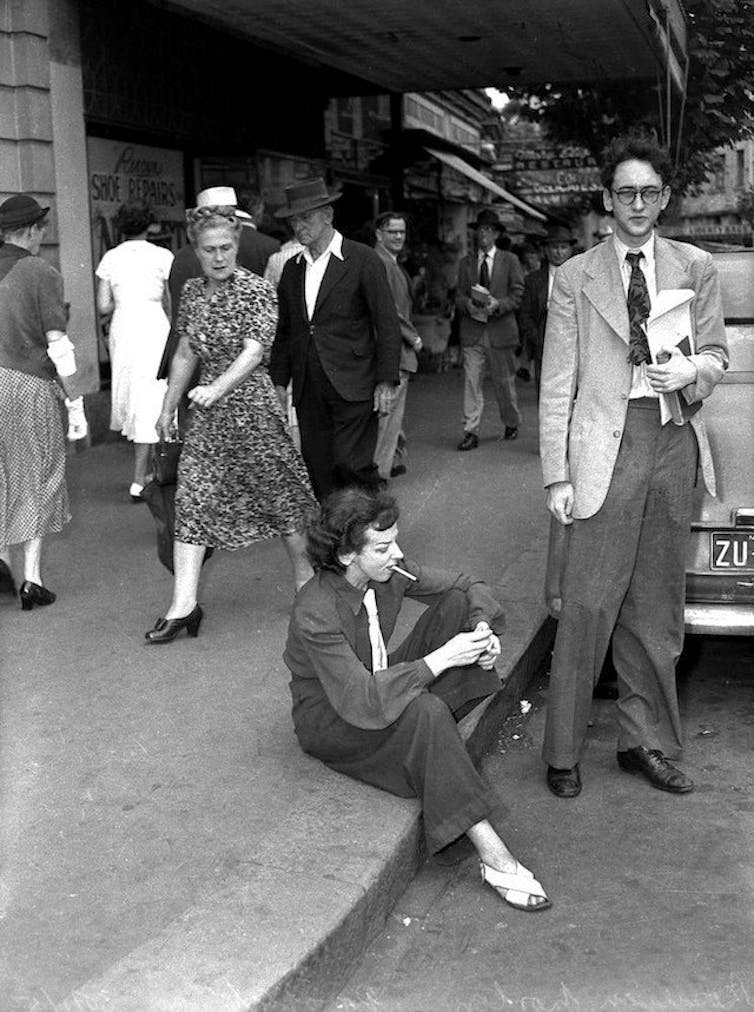

Rosaleen Norton and poet Gavin Greenlees, one of her lovers, photographed on Darlinghurst Road in 1950. Sydney Morning Herald.

Strands of magic

Norton and Greenlees practised several strands of magic, including trance magic, sex magic, and ceremonies combining and improvising elements from several traditions. These included Kundalini (the feminine, creative force of infinite wisdom that ‘lives’ inside us, usually represented by a snake) and Tantra (encompassing esoteric rituals and practices from Hindu and Buddhist traditions).

Norton explained that she employed these practices to augment her unconscious, inspire and empower her art, and commune with entities on other planes.

Norton’s trance magic, in states of self-hypnosis, was a continuation of her childhood visions and visitations. In correspondence with a psychologist in 1949, she described experiencing deities and projecting her astral body to contact other practitioners in alternative spiritual spheres. The idea, she wrote, was ‘to induce an abnormal state of consciousness and manifest the results, if any, in drawing’.

These experiences informed and inspired her art. Norton’s paintings were produced for her own ritual spaces, as well as for exhibitions and publications. In a well-known photograph from the 1950s, Norton is shown crouching at the base of her altar to Pan, replete with a large portrait of the god.

Norton in front of her altar to the god Pan, photographed in 1950. The Sydney Morning Herald/Black Jelly Films.

Pan features in many other works. As Norton said in 1957, his ‘pipes are a symbol of magic and mystery’, while his ‘horns and hooves stand for natural energies and fleet-footed freedom’.

Norton’s worship of Pan reflected her passion for animals, insects and nature in general. While she did not publicly campaign for animal rights, she was, in some respects, a forerunner of the movement. Regularly the target of outrageous media allegations, she was particularly incensed when asked whether, as a witch, she performed animal sacrifice.

In 1954, 89.4% of the Australian population identified as Christian. Unfortunately for Norton, the ancient Greek god Pan also resembles Christian representations of Satan or the Devil. Indeed with his goat legs, pointed ears, and lascivious face, Pan most likely inspired early Christian images of Satan. Norton was regularly asked whether she was a Satanist. She wasn’t. But, accusations of Satanism haunted her.

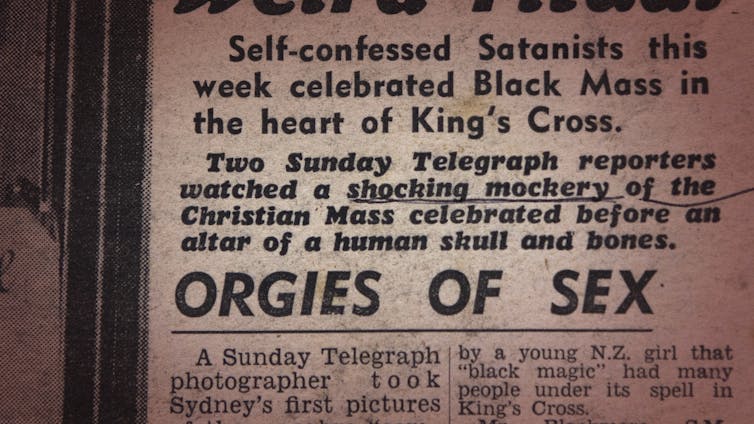

Journalists accused her of Devil worship, police occasionally placed her and Greenlees under surveillance, and her private life became fair game. By the 1950s, the tabloid press’ preferred name for Norton – ‘the witch of Kings Cross’ – had stuck. It featured in news stories on her even after her death.

Sensationalist claims about Norton were frequently published in Sydney’s newspapers, like here in the Sunday Telegraph. The Sunday Telegraph/Black Jelly Films.

Censorship and court proceedings

Norton’s run-ins with authorities are partly what make her such an important historical figure. Her early exhibitions were subject to media attention and sensationalism, censorship and court proceedings. During an exhibition of her art at Rowden-White Library, University of Melbourne, in 1949, the Vice Squad seized several works deemed to be profane. Norton appeared in court on obscenity charges – the first such case against a woman in Victoria.

While Norton was acquitted, more scandals erupted. Her collaboration with Greenlees on a book titled, The Art of Rosaleen Norton, with poems by Gavin Greenlees, published privately by Walter Glover in 1952, landed Glover and printer, Tonecraft Pty Ltd, in court on charges of producing an obscene publication.

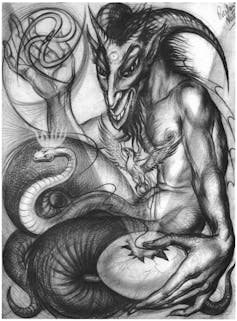

Fohat, one of Norton’s most famous and controversial works. Black Jelly Films, courtesy Burgess Family.

Glover was fined £5 and Tonecraft £1. The book was subject to a customs ban (copies sent to New York were confiscated and burnt by United States Customs) and it became a prohibited import to Australia.

Norton’s Fohat (one of the book’s notorious images) was a representation of her beliefs. The goat, she said, ‘is a symbol of energy and creativity: the serpent of elemental force and eternity’. As with the images of Pan (and many other artworks), the meaning behind Fohat was misconstrued, deemed obscene and Satanic.

The case of Sir Eugene Goossens

Norton’s practice of sex magic was at the centre of one sensational court case. Her private rituals concerning the practice (including, among other acts, anal and oral sex, and sado-masochism) involved a discrete group of devotees. One of them was the revered composer and conductor Sir Eugene Goossens (1893-1962).

As director of the New South Wales State Conservatorium and chief conductor of the ABC’s Sydney Symphony Orchestra, the English-born Goossens was a cultural and social giant in a still very parochial Australia. Having seen a copy of the infamous book by Norton and Greenlees, Goossens sought out the couple and soon became part of their occult practices and personal lives.

Caught up in their world, Goossens became an unsuspecting target of police surveillance. In March 1956, returning from an overseas trip, he was confronted with officers waiting to search his luggage and subsequently charged with importing prohibited items, allegedly including ‘indecent works and articles, namely a number of books, prints and photographs, and a quantity of film’.

Goossens was besieged day and night at his home, and newspapers screamed headlines, such as ‘BIG NAMES IN DEVIL RITE PROBE’.

Norton photographed with her cat in 1949. News Ltd.

Goossens’ life and career were ruined. He pleaded guilty to pornography charges in absentia at a hearing in Martin Place Court of Petty Sessions, was fined £100, and returned to the United Kingdom a broken man.

While the media and some biographers of Goossens still tend to blame Norton for contaminating him by inducting him into her unholy cult of sex magic, this could not be further from the truth.

In fact, Goossens came to Australia with significant experience in occult practices, actively seeking out Norton and Greenlees. Personal correspondence from Goossens to Norton reveals his role in mentoring his new friends in more advanced magic, and hints at a network of practitioners in the UK and Europe. Three of the extant letters are signed with Goossens’ magical name, ‘Djinn’.

Later life

Norton retired from public view during the 1970s, living in a basement flat in Roslyn Garden, with her sister, Cecily Boothman (1905-1991), close by in the same apartment block. Frail, in poor health, but an artist and witch to the end, Norton practised her rituals, painted and communed with animals and nature.

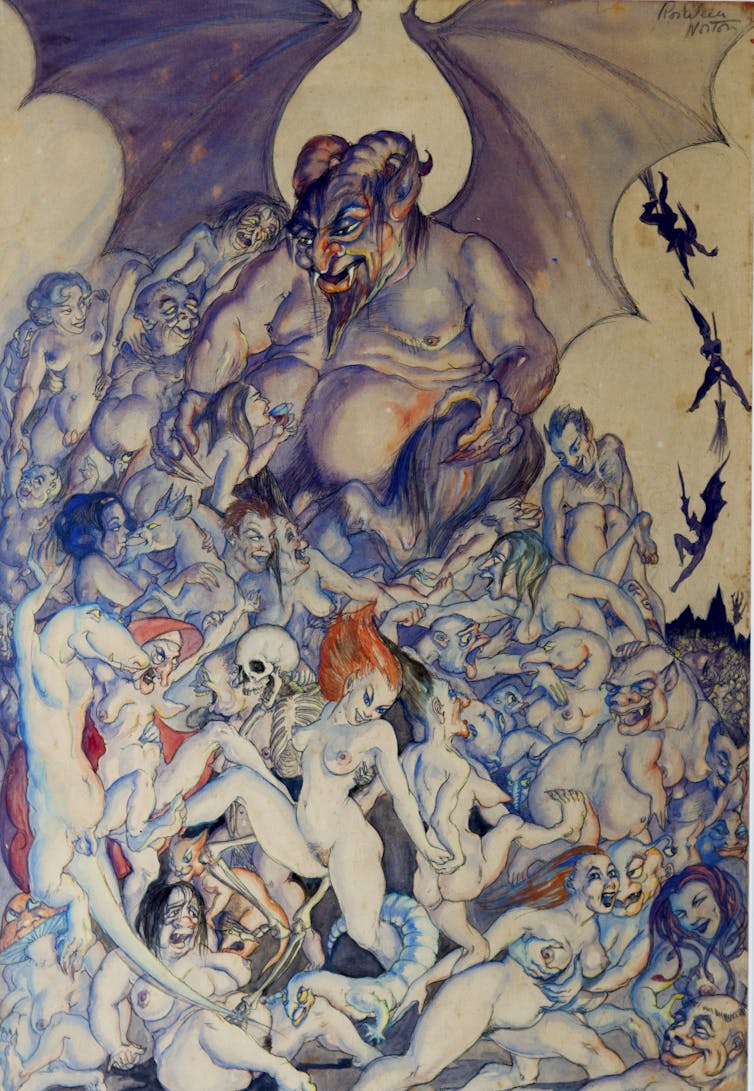

Rosaleen Norton’s Bacchanal. Black Jelly Films, courtesy Burgess Family.

She and Boothman were visited by Greenlees on his days of temporary release from the Alma Mater Nursing Home, Kensington, where he had been sectioned after a lengthy stay at Callan Park Mental Hospital at the age of 25.

At the age of 61, Norton was diagnosed with colon cancer. She died at the Sacred Heart Hospice for the Dying, in Darlinghurst, on 5 December 1979.

Norton has been the subject of biographies by Nevill Drury, a fictionalised account, Pagan, by Inez Baranay, and several plays (including a student production, on which I was dramaturg).

Rare footage also captures her at her rebellious best: ensconced in a Kings Cross cafe, talking about rejecting the ordinary life of wife and mother, the thought of which prompts her to say: ‘I’d go mad’.

Norton was more than a witch. When we look closer at a woman reviled by the media, we see a groundbreaking bohemian, committed to living freely and authentically, who challenged censorship.

In many ways, she helped to push Australia out of the safety of the Menzies era, into the civilising forces of the sexual revolution and the freedoms it brought.

The Witch of Kings Cross, written and directed by Sonia Bible, will be released on Amazon, iTunes, Vimeo and GooglePlay on 9th February and opens in selected cinemas from February 11.

Article written by Marguerite Johnson, Professor of Classics, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.