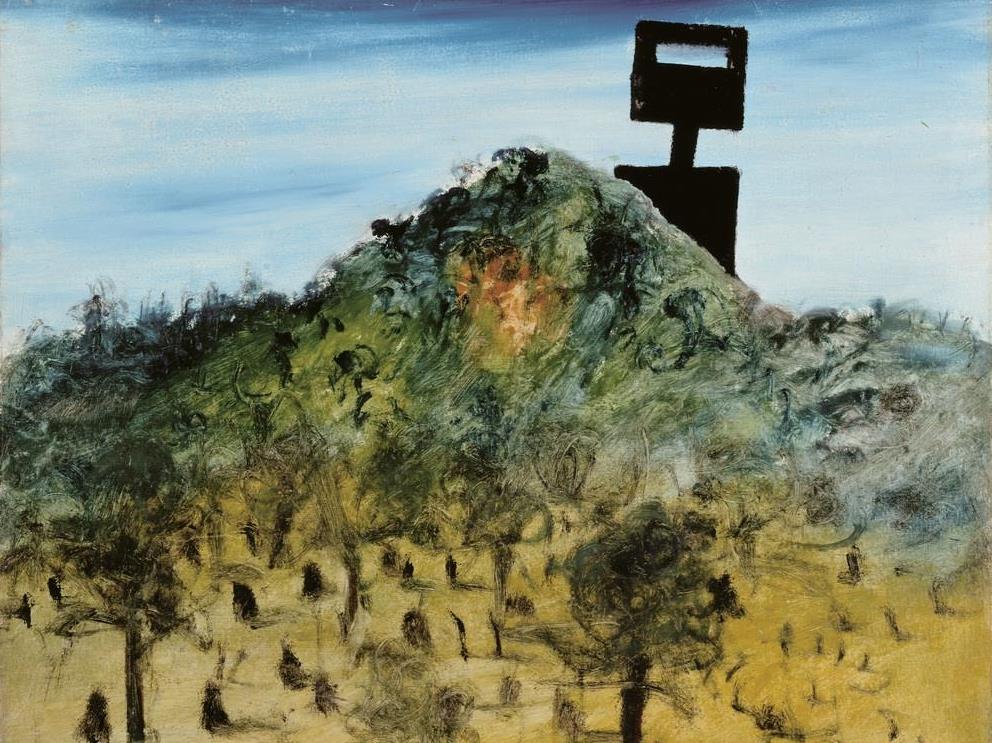

Sidney Nolan’s Kelly 1946, enamel on cardboard (detail), Canberra Museum & Gallery.

Some consider him an Australian Robin Hood; a republican and rebel who stood up to police persecution and the rural Squattocracy.

To others, such as the descendants of Sergeant Michael Kennedy and Constables Thomas Lonigan and Michael Scanlan, he is a cold-blooded killer.

Regardless of your perspective, it’s clear that the story of Ned Kelly and the Kelly Gang continues to inspire artists and arguments alike.

Poems and songs about Ned Kelly were first performed while the Gang was still at large (1878–80). By 1899, dramatists such as Arnold Denham were adopting Kelly’s story for the stage.

In 1906 came Charles Tait’s silent movie, The Story of the Kelly Gang – recognised by UNESCO as the world’s first feature-length film – followed by a range of similar films in the following years (indeed such was the genre’s popularity that a ban on bushranger movies came into effect in 1911-12, inadvertently sending the Australian film industry into decline).

Among the most influential artistic portrayals of Ned Kelly and the Kelly Gang are Sidney Nolan’s paintings from 1946–47; more recently, Peter Carey’s multi-award-winning True History of the Kelly Gang further helped enshrine the status of the Kelly Gang.

Not every exploration of the Kelly legend has been a success. Tony Richardson’s 1970 Ned Kelly, starring Mick Jagger in the title role, was poorly received. Similarly, Reg Livermore and Patrick Flynn’s 1977 musical (described as ‘an artistic disaster’ by the Adelaide Advertiser) and Gregor Jordan’s underwhelming 2003 film starring the late Heath Ledger are all testament to the challenges inherent in tackling an Australian icon.

But why does the story of an Irish-Australian bushranger who died in 1880 have such significant and enduring appeal – and why do artists continue to grapple with the story of the Kelly Gang in story and song today?

‘As an iconic Australian figure and source of Australian mythology, Ned can be looked at, at various times throughout history, to reflect quite contemporary issues – views of Australian identity and even the zeitgeist in Australia. He’s got that malleability, I think, as a figure to really radiate different perceptions on wider themes out to the public,’ said composer Luke Styles, whose new opera Ned Kelly will premiere at the Perth Festival in 2018.

Sydney-based choreographer and director Miranda Middleton, who is directing a new production of NED – A New Australian Musical at the New Theatre this month, also sees the Kelly Gang as speaking to the zeitgeist.

‘I think the Kelly Gang are a symbol of anti-authoritarianism, which in today’s political climate is resistance against the status quo. We’ve just seen thousands of Australian school students striking around the country for more governmental action on climate change. The same thing is happening in America against gun laws. So I think Ned’s status as the underdog who rebelled against the social order – whether or not that be in the right way – I think that still has an enduring appeal,’ Middleton told ArtsHub.

Heath Ledger in Ned Kelly (2003).

Even while Ned Kelly lived he was the focus of considerable fascination. The Kelly Gang’s activities coincided with the modernisation of the newspaper industry and the foundation of the earliest news agencies, and closely followed the spread of the telegraph system in Australia; factors which played a part in spreading word of the Gang’s depredations between 1878 and 1880, and embedding an awareness of their activities among the general public of the day.

‘That period in history was right at the beginnings of mass media culture, so the telegraph started operating around the same time and shortly after there were the first motion picture films. One of the first films ever made in Australia was about Ned Kelly, so he became very well-known across the whole of Australia … and that’s why artists have known his story,’ Ritale explained.

Ned Kelly’s status as an Irish-Australian was also a factor in his popularity. Following a sustained period of assisted immigration in the 1830s-1850s, Australia’s Irish population was considerable during the years the Kelly Gang operated.

Read: Why Australia still dances to an Irish tune

In 1871, when Victoria’s population numbered 100,468, more than one in four Victorians was born in Ireland – resulting in a sizeable and sympathetic audience hungry for news of Ned’s latest outrages against the English-born establishment.

‘And he also follows on quite soon after the Eureka Stockade, so there was quite a prevailing sentiment at that time of people struggling against the Squattocracy and government bureaucracy, so his deeds very much resonated at that time,’ Ritale said.

Heath Ledger in Ned Kelly (2003).

Even while Ned Kelly lived he was the focus of considerable fascination. The Kelly Gang’s activities coincided with the modernisation of the newspaper industry and the foundation of the earliest news agencies, and closely followed the spread of the telegraph system in Australia; factors which played a part in spreading word of the Gang’s depredations between 1878 and 1880, and embedding an awareness of their activities among the general public of the day.

‘That period in history was right at the beginnings of mass media culture, so the telegraph started operating around the same time and shortly after there were the first motion picture films. One of the first films ever made in Australia was about Ned Kelly, so he became very well-known across the whole of Australia … and that’s why artists have known his story,’ Ritale explained.

Ned Kelly’s status as an Irish-Australian was also a factor in his popularity. Following a sustained period of assisted immigration in the 1830s-1850s, Australia’s Irish population was considerable during the years the Kelly Gang operated.

Read: Why Australia still dances to an Irish tune

In 1871, when Victoria’s population numbered 100,468, more than one in four Victorians was born in Ireland – resulting in a sizeable and sympathetic audience hungry for news of Ned’s latest outrages against the English-born establishment.

‘And he also follows on quite soon after the Eureka Stockade, so there was quite a prevailing sentiment at that time of people struggling against the Squattocracy and government bureaucracy, so his deeds very much resonated at that time,’ Ritale said.

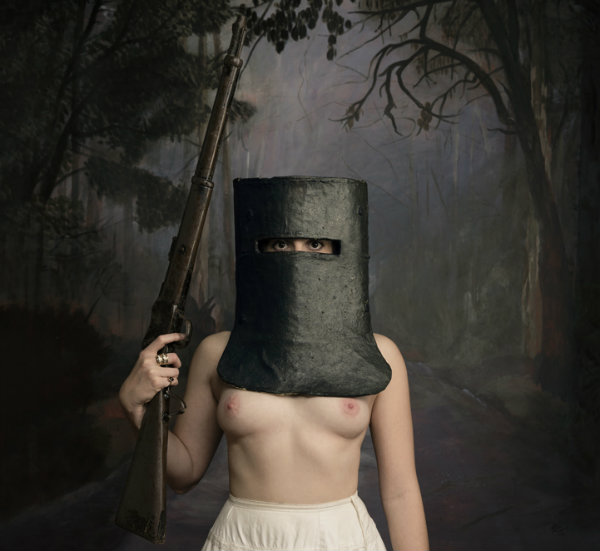

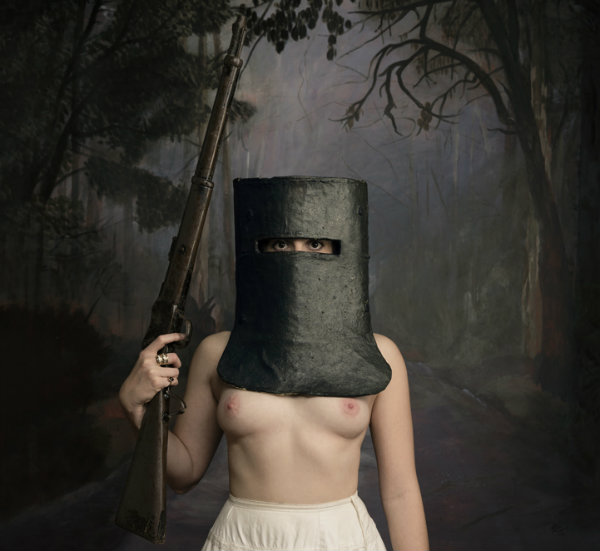

Jacqui Stockdale’s Historia (from the Boho series), detail, used as the promotional image for Lost & Found’s Ned Kelly. Image courtesy the artist and ThisIsNoFantasy+Dianne Tanzer.

On the other side of the country, new Australian company Plush Duck are also interested in drawing out similar aspects of the Kelly story through their new production of the Australian musical, NED, which originally premiered in Bendigo in 2015.

Miranda Middleton was also drawn to NED (composed by Adam Lyon, who also wrote the libretto, with a book by Anna Lyon and Marc McIntyre) because of its focus on the Kelly women.

‘I wanted to direct this musical because for me what it does is it tells another side of the Ned Kelly legend, and that’s the experience of the females in his life. So a really strong through-line throughout the musical is the hardships faced by his mother, Ellen Kelly, and her stoicism; and the strength of his sisters Maggie and Kate, who held the fort at home when their mother was put into jail and they looked after the other eight kids,’ she explained.

‘As a female director I feel as though our national narratives have been slightly deprived of female voices and female experiences, and what this show does beautifully is it does write the female experience into a traditionally male-dominated legend.’

Jacqui Stockdale’s Historia (from the Boho series), detail, used as the promotional image for Lost & Found’s Ned Kelly. Image courtesy the artist and ThisIsNoFantasy+Dianne Tanzer.

On the other side of the country, new Australian company Plush Duck are also interested in drawing out similar aspects of the Kelly story through their new production of the Australian musical, NED, which originally premiered in Bendigo in 2015.

Miranda Middleton was also drawn to NED (composed by Adam Lyon, who also wrote the libretto, with a book by Anna Lyon and Marc McIntyre) because of its focus on the Kelly women.

‘I wanted to direct this musical because for me what it does is it tells another side of the Ned Kelly legend, and that’s the experience of the females in his life. So a really strong through-line throughout the musical is the hardships faced by his mother, Ellen Kelly, and her stoicism; and the strength of his sisters Maggie and Kate, who held the fort at home when their mother was put into jail and they looked after the other eight kids,’ she explained.

‘As a female director I feel as though our national narratives have been slightly deprived of female voices and female experiences, and what this show does beautifully is it does write the female experience into a traditionally male-dominated legend.’

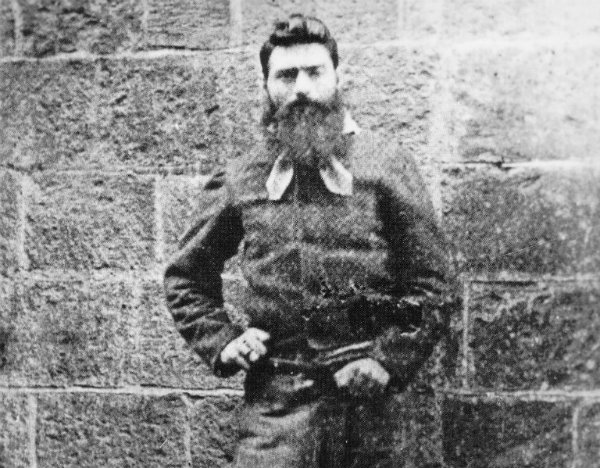

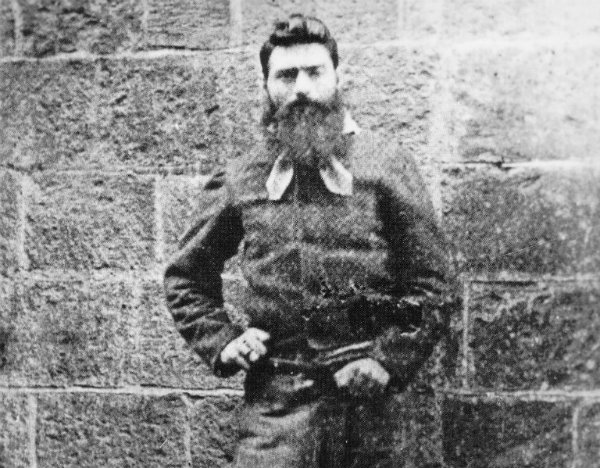

A photograph of Ned Kelly taken shortly before his execution in 1880.

The heightened drama of the Kelly Gang’s activities are also well-suited to the operatic form, he continued.

‘I think it’s particularly suitable for opera because it’s an extraordinary story. We’re not talking about everyday events; we’re not talking everyday individuals either – these are people who were pushed to extremes and that exist in a world which is not our world today. And that’s for me the key to opera.

‘If we look at The Cunning Little Vixen they live in a world of singing animals; The Magic Flute – we don’t have the Queen of the Night singing to us when we walk down the street. Certainly those highs and lows of emotion but also the extremity and the almost fantastical natures of the Kelly Gang make them appropriate for opera,’ said Styles.

A photograph of Ned Kelly taken shortly before his execution in 1880.

The heightened drama of the Kelly Gang’s activities are also well-suited to the operatic form, he continued.

‘I think it’s particularly suitable for opera because it’s an extraordinary story. We’re not talking about everyday events; we’re not talking everyday individuals either – these are people who were pushed to extremes and that exist in a world which is not our world today. And that’s for me the key to opera.

‘If we look at The Cunning Little Vixen they live in a world of singing animals; The Magic Flute – we don’t have the Queen of the Night singing to us when we walk down the street. Certainly those highs and lows of emotion but also the extremity and the almost fantastical natures of the Kelly Gang make them appropriate for opera,’ said Styles.

Ned Kelly’s armour is displayed in the Changing face of Victoria exhibition at State Library Victoria.

Plush Duck’s pro-am production of NED features many professional music theatre performers, but under Middleton’s direction will have a strong focus on movement.

‘Adam Lyons’ score spoke to me immediately – I had immediate visions of what I wanted to do in terms of movement,’ she said.

‘I’ve been predominantly a choreographer up until now and I believe that the human body can really extend the storytelling which is told through dialogue and lyrics, so my vision for the show is quite movement-heavy … drawing out the actors’ emotional responses to their characters’ experiences through not just voice but also their movement and their physicality.

‘There’s only one number in the show that has real presentational choreography, ‘Sing, Dance, Drink, Love’; with the rest of the musical numbers it’s very much not choreography per se, it’s not dance per se, it’s movement that reflects the actors’ and the characters’ emotions and experiences. For a lot of those numbers it’s quite weighted movement, it’s very grounded, and I’ve been really trying to extract from the cast a genuine and authentic feeling of hardship, of living in early colonial Australia and expressing that physically,’ Middleton said.

Storytelling of a different kind can be seen in the Jerilderie Letter at State Library Victoria; a remarkable document believed to be written by Kelly Gang member Joe Byrne, and dictated by Ned himself.

‘The Jerilderie Letter is probably one of our most interesting items in our collection,’ Jo Ritale said.

‘It is very much Ned Kelly’s voice but we believe it is written by Joe Byrne, who was probably the most educated of the Kelly Gang, but it is Ned’s phrasing and terminology … and it is very much a passionate statement about what has happened, why he was doing what he was doing, what his justification was and what his intentions were. And the unique phrases that he uses very much inspired Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang – an amazing book … Carey used the Jerilderie Letter to create a character that really comes to life in that work.

‘I suppose I think it’s evidence of how Ned’s story and the way he worded his cause mean that people still really connect to it, and I suppose that’s why artists continue to reinterpret the Kelly Gang story, and why writers continue to be fascinated with it,’ Ritale concluded.

Lost & Found’s Ned Kelly premieres at Perth Festival from 15-19 February 2019

Plush Duck Productions’ NED – A New Australian Musical is at the New Theatre, Newtown from 18-22 December 2018

The National Gallery of Australia’s travelling exhibition, Ned Kelly, is currently showing at Murray Art Museum Albury until 17 February 2019, before showing at Geelong Gallery from 2 March to 26 May 2019.

Ned Kelly’s armour and other items of Kelly memorabilia, including his death mask, are on permanent display at State Library Victoria: see https://www.slv.vic.gov.au/search-discover/explore-collections-theme/australian-history/ned-kelly for details.

Ned Kelly’s armour is displayed in the Changing face of Victoria exhibition at State Library Victoria.

Plush Duck’s pro-am production of NED features many professional music theatre performers, but under Middleton’s direction will have a strong focus on movement.

‘Adam Lyons’ score spoke to me immediately – I had immediate visions of what I wanted to do in terms of movement,’ she said.

‘I’ve been predominantly a choreographer up until now and I believe that the human body can really extend the storytelling which is told through dialogue and lyrics, so my vision for the show is quite movement-heavy … drawing out the actors’ emotional responses to their characters’ experiences through not just voice but also their movement and their physicality.

‘There’s only one number in the show that has real presentational choreography, ‘Sing, Dance, Drink, Love’; with the rest of the musical numbers it’s very much not choreography per se, it’s not dance per se, it’s movement that reflects the actors’ and the characters’ emotions and experiences. For a lot of those numbers it’s quite weighted movement, it’s very grounded, and I’ve been really trying to extract from the cast a genuine and authentic feeling of hardship, of living in early colonial Australia and expressing that physically,’ Middleton said.

Storytelling of a different kind can be seen in the Jerilderie Letter at State Library Victoria; a remarkable document believed to be written by Kelly Gang member Joe Byrne, and dictated by Ned himself.

‘The Jerilderie Letter is probably one of our most interesting items in our collection,’ Jo Ritale said.

‘It is very much Ned Kelly’s voice but we believe it is written by Joe Byrne, who was probably the most educated of the Kelly Gang, but it is Ned’s phrasing and terminology … and it is very much a passionate statement about what has happened, why he was doing what he was doing, what his justification was and what his intentions were. And the unique phrases that he uses very much inspired Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang – an amazing book … Carey used the Jerilderie Letter to create a character that really comes to life in that work.

‘I suppose I think it’s evidence of how Ned’s story and the way he worded his cause mean that people still really connect to it, and I suppose that’s why artists continue to reinterpret the Kelly Gang story, and why writers continue to be fascinated with it,’ Ritale concluded.

Lost & Found’s Ned Kelly premieres at Perth Festival from 15-19 February 2019

Plush Duck Productions’ NED – A New Australian Musical is at the New Theatre, Newtown from 18-22 December 2018

The National Gallery of Australia’s travelling exhibition, Ned Kelly, is currently showing at Murray Art Museum Albury until 17 February 2019, before showing at Geelong Gallery from 2 March to 26 May 2019.

Ned Kelly’s armour and other items of Kelly memorabilia, including his death mask, are on permanent display at State Library Victoria: see https://www.slv.vic.gov.au/search-discover/explore-collections-theme/australian-history/ned-kelly for details.

Made by the media?

Jo Ritale, Head of Collections at State Library Victoria (SLV), which counts Ned’s armour and the famous Jerilderie Letter among its collection, believes Kelly’s enduring legacy is in part driven by the fierce debates around his real-life activities. ‘There’s two distinct points of view of Ned Kelly and the activities of the Kelly Gang. One is very much around the idea of Ned as an Australian version of Robin Hood, where he was championing the cause of those who were struggling at the time and being oppressed, and then there’s that side where they think of Ned very much as a criminal, whose actions were really contrary to what was socially acceptable,’ she said. ‘I think those really passionate views contribute to the fact that his story still resonates and has historical interest because there is such passion from both sides.’ Heath Ledger in Ned Kelly (2003).

Even while Ned Kelly lived he was the focus of considerable fascination. The Kelly Gang’s activities coincided with the modernisation of the newspaper industry and the foundation of the earliest news agencies, and closely followed the spread of the telegraph system in Australia; factors which played a part in spreading word of the Gang’s depredations between 1878 and 1880, and embedding an awareness of their activities among the general public of the day.

‘That period in history was right at the beginnings of mass media culture, so the telegraph started operating around the same time and shortly after there were the first motion picture films. One of the first films ever made in Australia was about Ned Kelly, so he became very well-known across the whole of Australia … and that’s why artists have known his story,’ Ritale explained.

Ned Kelly’s status as an Irish-Australian was also a factor in his popularity. Following a sustained period of assisted immigration in the 1830s-1850s, Australia’s Irish population was considerable during the years the Kelly Gang operated.

Read: Why Australia still dances to an Irish tune

In 1871, when Victoria’s population numbered 100,468, more than one in four Victorians was born in Ireland – resulting in a sizeable and sympathetic audience hungry for news of Ned’s latest outrages against the English-born establishment.

‘And he also follows on quite soon after the Eureka Stockade, so there was quite a prevailing sentiment at that time of people struggling against the Squattocracy and government bureaucracy, so his deeds very much resonated at that time,’ Ritale said.

Heath Ledger in Ned Kelly (2003).

Even while Ned Kelly lived he was the focus of considerable fascination. The Kelly Gang’s activities coincided with the modernisation of the newspaper industry and the foundation of the earliest news agencies, and closely followed the spread of the telegraph system in Australia; factors which played a part in spreading word of the Gang’s depredations between 1878 and 1880, and embedding an awareness of their activities among the general public of the day.

‘That period in history was right at the beginnings of mass media culture, so the telegraph started operating around the same time and shortly after there were the first motion picture films. One of the first films ever made in Australia was about Ned Kelly, so he became very well-known across the whole of Australia … and that’s why artists have known his story,’ Ritale explained.

Ned Kelly’s status as an Irish-Australian was also a factor in his popularity. Following a sustained period of assisted immigration in the 1830s-1850s, Australia’s Irish population was considerable during the years the Kelly Gang operated.

Read: Why Australia still dances to an Irish tune

In 1871, when Victoria’s population numbered 100,468, more than one in four Victorians was born in Ireland – resulting in a sizeable and sympathetic audience hungry for news of Ned’s latest outrages against the English-born establishment.

‘And he also follows on quite soon after the Eureka Stockade, so there was quite a prevailing sentiment at that time of people struggling against the Squattocracy and government bureaucracy, so his deeds very much resonated at that time,’ Ritale said.

Reflecting the zeitgeist

Chris van Tuinen is the Artistic Director of Perth company Lost & Found, the commissioners of Luke Styles’ and librettist Peter Goldsworthy’s opera, Ned Kelly. ‘When we started Lost & Found, Thomas de Mallet Burgess and I had always planned on commissioning a work. Being an Australian company that produces work in Perth we were certain that this needed to be an Australian story and one that reflected on the experience of our place, history or identity,’ said van Tuinen. ‘The Ned mythology permeates much of the current Australian identity, particularly around masculinity, morality and responses to authority. That story is being unpacked to this day and what seemed interesting to us (and thus is part of the opera) is to involve the lesser known aspects of the Kelly story. ‘For example the opera brings several things to the foreground : his mother Ellen and sister Kate, the republican aspirations, the gang’s motivations and conflicts around their crimes, and the hiding of identity through masks and disguises (especially in Steve Hart’s case through cross dressing!),’ van Tuinen said. Jacqui Stockdale’s Historia (from the Boho series), detail, used as the promotional image for Lost & Found’s Ned Kelly. Image courtesy the artist and ThisIsNoFantasy+Dianne Tanzer.

On the other side of the country, new Australian company Plush Duck are also interested in drawing out similar aspects of the Kelly story through their new production of the Australian musical, NED, which originally premiered in Bendigo in 2015.

Miranda Middleton was also drawn to NED (composed by Adam Lyon, who also wrote the libretto, with a book by Anna Lyon and Marc McIntyre) because of its focus on the Kelly women.

‘I wanted to direct this musical because for me what it does is it tells another side of the Ned Kelly legend, and that’s the experience of the females in his life. So a really strong through-line throughout the musical is the hardships faced by his mother, Ellen Kelly, and her stoicism; and the strength of his sisters Maggie and Kate, who held the fort at home when their mother was put into jail and they looked after the other eight kids,’ she explained.

‘As a female director I feel as though our national narratives have been slightly deprived of female voices and female experiences, and what this show does beautifully is it does write the female experience into a traditionally male-dominated legend.’

Jacqui Stockdale’s Historia (from the Boho series), detail, used as the promotional image for Lost & Found’s Ned Kelly. Image courtesy the artist and ThisIsNoFantasy+Dianne Tanzer.

On the other side of the country, new Australian company Plush Duck are also interested in drawing out similar aspects of the Kelly story through their new production of the Australian musical, NED, which originally premiered in Bendigo in 2015.

Miranda Middleton was also drawn to NED (composed by Adam Lyon, who also wrote the libretto, with a book by Anna Lyon and Marc McIntyre) because of its focus on the Kelly women.

‘I wanted to direct this musical because for me what it does is it tells another side of the Ned Kelly legend, and that’s the experience of the females in his life. So a really strong through-line throughout the musical is the hardships faced by his mother, Ellen Kelly, and her stoicism; and the strength of his sisters Maggie and Kate, who held the fort at home when their mother was put into jail and they looked after the other eight kids,’ she explained.

‘As a female director I feel as though our national narratives have been slightly deprived of female voices and female experiences, and what this show does beautifully is it does write the female experience into a traditionally male-dominated legend.’

The impact of an icon

While Luke Styles was originally drawn to the iconography of the Kelly Gang’s crude armour, fashioned – in a reversal of the Biblical exhortation – from plough blades, he soon discovered deeper themes that were suited to the operatic form. ‘In researching Ned and the gang, his family particularly – his mother and sister – it was clear from the whole story, and the whole society of the time, that there were a number of operatic elements, and ways in which to make this an operatic piece of theatre,’ he said. ‘So, the fact that he was a complex itinerant bush worker with a number of different skills – that he was a fence-splitter, a mason, a beekeeper, a whiskey distiller as well as the areas in which he’s most notorious – meant that Ned himself had these shifting identities and different uniforms, working out who he was. ‘He was also someone who took on a lot of traditionally female roles within that society – cooking, cleaning, child-rearing – which was a necessity in these frontier bush communities. And that’s an aspect of Ned as the gun-toting bushranger folk hero that we don’t really hear about. We don’t hear about him looking after babies, cooking food, being the one to support the family with his single mum after dad died. And it’s these kinds of complexities that allow him to be an operatic figure,’ Styles said. A photograph of Ned Kelly taken shortly before his execution in 1880.

The heightened drama of the Kelly Gang’s activities are also well-suited to the operatic form, he continued.

‘I think it’s particularly suitable for opera because it’s an extraordinary story. We’re not talking about everyday events; we’re not talking everyday individuals either – these are people who were pushed to extremes and that exist in a world which is not our world today. And that’s for me the key to opera.

‘If we look at The Cunning Little Vixen they live in a world of singing animals; The Magic Flute – we don’t have the Queen of the Night singing to us when we walk down the street. Certainly those highs and lows of emotion but also the extremity and the almost fantastical natures of the Kelly Gang make them appropriate for opera,’ said Styles.

A photograph of Ned Kelly taken shortly before his execution in 1880.

The heightened drama of the Kelly Gang’s activities are also well-suited to the operatic form, he continued.

‘I think it’s particularly suitable for opera because it’s an extraordinary story. We’re not talking about everyday events; we’re not talking everyday individuals either – these are people who were pushed to extremes and that exist in a world which is not our world today. And that’s for me the key to opera.

‘If we look at The Cunning Little Vixen they live in a world of singing animals; The Magic Flute – we don’t have the Queen of the Night singing to us when we walk down the street. Certainly those highs and lows of emotion but also the extremity and the almost fantastical natures of the Kelly Gang make them appropriate for opera,’ said Styles.

The art of storytelling

Musically, Lost & Found’s Ned Kelly will incorporate some of the songs that Ned Kelly himself may have known, as well as the influences of Britten, Purcell and Styles’ teacher, Wolfgang Rihm. ‘There’s two existing folk songs in the piece: ‘The Wild Colonial Boy’, which Peter has rewritten as ‘The Wild Colonial Girl’ because Ellen Kelly is front and centre in the opera – she certainly frames it – and ‘Moreton Bay’ is also in the work. And this comes from not evidence as such but hearsay and testimony at the time that Ned was quite a good singer, and our idea was that Ned was taught these songs by his mum. And you certainly have little bits of ‘Moreton Bay’ quoted in the Jerilderie Letter, and so that felt like he must have known that tune. And so to emphasise that there’s an on-stage folk band – a little bit like how Britten uses a guitar player, a narrator-guitar player – in Paul Bunyan,’ Styles said. ‘So that’s one level of the music. The other is just straight Styles … And the orchestra around it plays a very different harmonic and textural world. There’s a lot of percussive music in it, particularly when we get to Glenrowan. We hear throughout the opera these kind of metallic sounds – which could almost be Siegfried forging his sword, but we have Ned forging his armour, or remnants of Nibelheim but on corrugated iron rather than on an anvil. ‘And then the other level, and at Stringybark [Creek] in particular I would say is, the bush comes into the piece. So we hear a lot of non-pitched sounds that the chorus will make – whispering and hissing noises. We hear gum-leaves, we hear a lot of non-pitched sounds from the strings and the winds, so it opens up a very ethereal space, I’d say.’ Ned Kelly’s armour is displayed in the Changing face of Victoria exhibition at State Library Victoria.

Plush Duck’s pro-am production of NED features many professional music theatre performers, but under Middleton’s direction will have a strong focus on movement.

‘Adam Lyons’ score spoke to me immediately – I had immediate visions of what I wanted to do in terms of movement,’ she said.

‘I’ve been predominantly a choreographer up until now and I believe that the human body can really extend the storytelling which is told through dialogue and lyrics, so my vision for the show is quite movement-heavy … drawing out the actors’ emotional responses to their characters’ experiences through not just voice but also their movement and their physicality.

‘There’s only one number in the show that has real presentational choreography, ‘Sing, Dance, Drink, Love’; with the rest of the musical numbers it’s very much not choreography per se, it’s not dance per se, it’s movement that reflects the actors’ and the characters’ emotions and experiences. For a lot of those numbers it’s quite weighted movement, it’s very grounded, and I’ve been really trying to extract from the cast a genuine and authentic feeling of hardship, of living in early colonial Australia and expressing that physically,’ Middleton said.

Storytelling of a different kind can be seen in the Jerilderie Letter at State Library Victoria; a remarkable document believed to be written by Kelly Gang member Joe Byrne, and dictated by Ned himself.

‘The Jerilderie Letter is probably one of our most interesting items in our collection,’ Jo Ritale said.

‘It is very much Ned Kelly’s voice but we believe it is written by Joe Byrne, who was probably the most educated of the Kelly Gang, but it is Ned’s phrasing and terminology … and it is very much a passionate statement about what has happened, why he was doing what he was doing, what his justification was and what his intentions were. And the unique phrases that he uses very much inspired Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang – an amazing book … Carey used the Jerilderie Letter to create a character that really comes to life in that work.

‘I suppose I think it’s evidence of how Ned’s story and the way he worded his cause mean that people still really connect to it, and I suppose that’s why artists continue to reinterpret the Kelly Gang story, and why writers continue to be fascinated with it,’ Ritale concluded.

Lost & Found’s Ned Kelly premieres at Perth Festival from 15-19 February 2019

Plush Duck Productions’ NED – A New Australian Musical is at the New Theatre, Newtown from 18-22 December 2018

The National Gallery of Australia’s travelling exhibition, Ned Kelly, is currently showing at Murray Art Museum Albury until 17 February 2019, before showing at Geelong Gallery from 2 March to 26 May 2019.

Ned Kelly’s armour and other items of Kelly memorabilia, including his death mask, are on permanent display at State Library Victoria: see https://www.slv.vic.gov.au/search-discover/explore-collections-theme/australian-history/ned-kelly for details.

Ned Kelly’s armour is displayed in the Changing face of Victoria exhibition at State Library Victoria.

Plush Duck’s pro-am production of NED features many professional music theatre performers, but under Middleton’s direction will have a strong focus on movement.

‘Adam Lyons’ score spoke to me immediately – I had immediate visions of what I wanted to do in terms of movement,’ she said.

‘I’ve been predominantly a choreographer up until now and I believe that the human body can really extend the storytelling which is told through dialogue and lyrics, so my vision for the show is quite movement-heavy … drawing out the actors’ emotional responses to their characters’ experiences through not just voice but also their movement and their physicality.

‘There’s only one number in the show that has real presentational choreography, ‘Sing, Dance, Drink, Love’; with the rest of the musical numbers it’s very much not choreography per se, it’s not dance per se, it’s movement that reflects the actors’ and the characters’ emotions and experiences. For a lot of those numbers it’s quite weighted movement, it’s very grounded, and I’ve been really trying to extract from the cast a genuine and authentic feeling of hardship, of living in early colonial Australia and expressing that physically,’ Middleton said.

Storytelling of a different kind can be seen in the Jerilderie Letter at State Library Victoria; a remarkable document believed to be written by Kelly Gang member Joe Byrne, and dictated by Ned himself.

‘The Jerilderie Letter is probably one of our most interesting items in our collection,’ Jo Ritale said.

‘It is very much Ned Kelly’s voice but we believe it is written by Joe Byrne, who was probably the most educated of the Kelly Gang, but it is Ned’s phrasing and terminology … and it is very much a passionate statement about what has happened, why he was doing what he was doing, what his justification was and what his intentions were. And the unique phrases that he uses very much inspired Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang – an amazing book … Carey used the Jerilderie Letter to create a character that really comes to life in that work.

‘I suppose I think it’s evidence of how Ned’s story and the way he worded his cause mean that people still really connect to it, and I suppose that’s why artists continue to reinterpret the Kelly Gang story, and why writers continue to be fascinated with it,’ Ritale concluded.

Lost & Found’s Ned Kelly premieres at Perth Festival from 15-19 February 2019

Plush Duck Productions’ NED – A New Australian Musical is at the New Theatre, Newtown from 18-22 December 2018

The National Gallery of Australia’s travelling exhibition, Ned Kelly, is currently showing at Murray Art Museum Albury until 17 February 2019, before showing at Geelong Gallery from 2 March to 26 May 2019.

Ned Kelly’s armour and other items of Kelly memorabilia, including his death mask, are on permanent display at State Library Victoria: see https://www.slv.vic.gov.au/search-discover/explore-collections-theme/australian-history/ned-kelly for details.