Don Bemrose as Bob Crab in State Opera SA’s Cloudstreet. Photo credit: Accent Photography.

‘Having a national identity is like having an old insurance policy. You know you’ve got one somewhere but you’re not sure where it is. And if you’re honest, you would have to admit you’re pretty vague about what the small print means’ – novelist William McIlvaney

Voss might be seen as a watershed in the evolution of Australian opera – a large-scale work tackling critical social and political issues. In the three decades since then, contemporary operas have tackled an eclectic range of topics, from book adaptations, including Tim Winton’s Cloudstreet and The Riders, to the Lindy Chamberlain case and the murder of Maria Korp by her husband in Midnight Son. This varied subject matter has demanded an equally eclectic musical idiom.

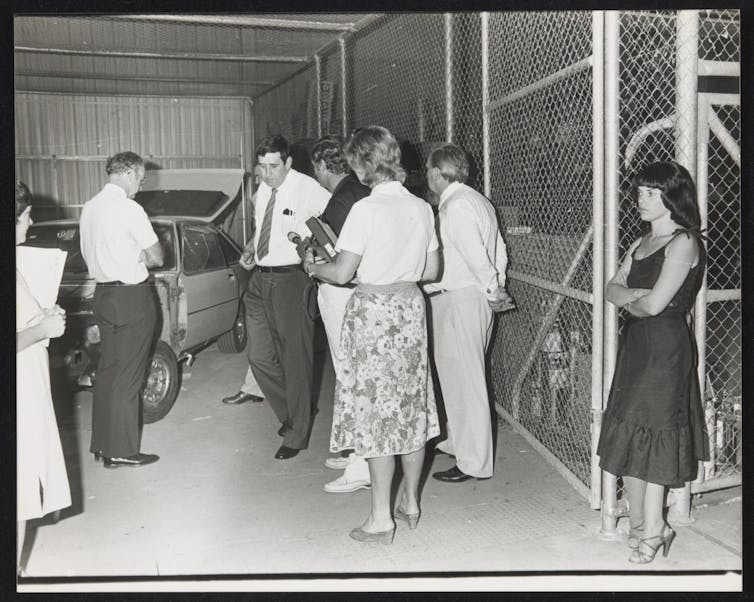

Lindy Chamberlain (right) as the second inquest views evidence from the Chamberlains’ car in Alice Springs, December, 1981. An opera of her story, Moya Henderson’s Lindy, was produced in 2002 but has not been staged since. National Museum of Australia

It is difficult to identify a distinctive Australian operatic “voice” as such, either in the choice of subject matter for libretti, or in the musical means employed. Australian composers have been caught up in the many currents that have engulfed classical music during this period.

One of the major issues confronting Australian opera composers is the lack of repeat productions of their works. Of nearly 20 important operas premiered in this period only two, Bliss (based on the Peter Carey novel) and The Eighth Wonder, have received a new staging.

Second productions, while not as “glamorous” as a premiere, are important for composers to refine their work. The “one production” phenomenon is not unique to Australia, but it results in a lack of a canon of local works.

Tackling difficult subjects

The policy of the major opera companies in commissioning new resource-intensive works, while not completely discarded, seems to be in decline. Much of the innovation and excitement of new opera is to be found in the small regional and city-based companies that might do only two productions a year. Frequently one of these is a new work, often by a composer new to opera. This could lead to more Indigenous opera being staged, but perhaps not the grand, sweeping works of the past.

It seemed that Voss might have been the catalyst for a new wave of operas that would tackle difficult and often controversial subjects. This has happened to some extent, but not in any systematic sense. Ironically, Voss is possibly the most talked-about but least read of canonical Australian novels.

Two other iconic Australian literary works adapted as operas are Ray Lawler’s play, The Summer of the Seventeenth Doll (1955), and Tim Winton’s novel, Cloudstreet (1991). Both reflect the tensions of the increasing urbanisation of Australia, while the dominant myths of an early, predominantly rural, pioneering and almost exclusively white history are increasingly seen as problematic, exclusionary and inadequate to embody a new reality.

Richard Mills and Peter Goldsworthy’s Doll was premiered in Melbourne in 1995 to a mixed reception. Controversy dogged Mills’s large-scale Batavia (2001) as well, with the critical reaction prompting a defence of the work by librettist Goldsworthy in newspapers and other outlets. No such controversy surrounded George Palmer’s version of Cloudstreet (2016), couched largely in a music theatre idiom.

There seems to be a kinder reception for the more recent operas. This was particularly so for the highly successful adaptation of John Marsden and Shaun Tan’s The Rabbits, by singer Kate Miller-Heidke, with libretto by Lally Katz, in collaboration with composer Iain Grandage, whose own operatic adaptation of Tim Winton’s The Riders was acclaimed in Melbourne in 2016. The Rabbits draws on musical theatre, opera and pop, and had sold-out runs in Perth, Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane, as well as a CD release.

But contemporary opera has not shied away from difficult and controversial subjects. Gillian Whitehead’s Bride of Fortune (1988) dealt with the subject of post-war Italian migration to Australia in a highly effective, and moving manner. Andrew Schultz’s Black River (1989) tackled the subject of Aboriginal deaths in custody. It was later made into an award-winning film (1993) by Kevin Lucas.

Similarly, Pecan Summer (2010), by Deborah Cheetham, deals with the Stolen Generations. Cheetham has used the opera as a means of training many Indigenous performers, and its final moments, which incorporate parts of Kevin Rudd’s parliamentary apology, are some of the most powerful in recent opera.

Permission to fail

The Eighth Wonder, with libretto by Dennis Watkins and music by Alan John, was premiered in 1995 in Sydney. Appropriately, as the subject matter is the building of the Sydney Opera House; this production was revived during the 2000 Olympic Games.

In 2016, a completely new production was staged on the steps of the Opera House. The orchestra and chorus were housed inside as the audience watched outside, with the building looming in the background, the sound provided through state-of-the-art headphones. This was a vividly meta-theatrical experience.

Brett Dean’s Bliss (2010) also enjoyed a second production after initial performances in Sydney, Melbourne and Edinburgh. Conductor Simone Young staged the work in Hamburg, where she was music director. (Incidentally, Dean’s Hamlet (2017) was critically acclaimed in the UK and Adelaide, and is slated for productions at the New York Metropolitan and in Europe.)

It seems opera in Australia is consistently moving away from works on an epic scale to those that do not require the large resources that were available in the past. But what some of these smaller-scale works sometimes reveal is a lack of understanding of the fundamental and essential theatricality of the art form.

Robert Fink, in After the Canon, notes: ‘the enduring vitality of opera will derive not from well-wrought musical structures, but from its continued ability to involve audiences in the emotional spectacle of a well-staged drama’.

The Artistic Director of Opera Australia, Lyndon Terracini, claims in a recent newspaper interview that since 1973, the Australia Council has commissioned ‘well over 160 operas or musical theatre pieces’ but ‘not one of them has entered the repertoire’ (that is, had a second production).

If not completely accurate, this remains a depressing statistic, and one might speculate that Fink’s point is relevant here. Many, perhaps most, of these works suffered from a lack of an innate sense of theatre due to the composers’ inexperience, ignorance or perhaps a touch of arrogance about the nature of opera and its particular demands.

Relevant to this is that composers be allowed to fail – how many of the great opera composers of the past succeeded with their first work? Almost all had a long and often frustrating apprenticeship. Writing interesting and well-crafted music is just one aspect of the operatic art. But the chance to try out new works – the way in which Broadway musicals were refined – is too expensive for the major companies today. Second productions do not have drawing power of a premiere.

Timothy Sexton, the previous Artistic Director of State Opera of South Australia, describes the recently-premiered Cloudstreet as being marketed as a music theatre work: ‘It straddles that middle line between a musical and what people think of as opera.’ He sees part of the problem as audiences being ‘reluctant around Australian operas because they’re exposed to them less than Australian theatre, visual art or pop music’. This is an issue that continues to dog new opera.

In America, argue Canadian academics Linda and Michael Hutcheon, contemporary American opera is no longer an elitist form of high art; it openly seeks to be accessible to a wider audience, while still remaining an art form. This has meant regional opera has expanded enormously, as has opera in colleges and universities. In fact, opera in the US and perhaps even in Europe is arguably the healthiest of all the forms of classical music today. This is perhaps in part because it has embraced its popular roots and broken down the barriers once set up between opera and Broadway musicals, cinema, jazz, and even rock music. This is yet another way in which, for opera, what’s old is new again.

While their view might be somewhat optimistic, the range of new American opera is, on any level, impressive. Although a much smaller country operatically speaking, this is not true for Australia. The National Opera Review of 2016 painted a picture that has some positive aspects, although the financial situation for some of the major companies was not encouraging. It also highlighted the lack of imagination in the planning of repertoire, as well as a dearth of new opera. Opportunities for local performers were seen as shrinking, as was the breadth and range of the repertoire.

Linking funding to new work

Opera is part of broader cultural politics, and the future of opera in Australia is an aspect of a wider political and cultural debate. Funding is a crucial issue for the development of the art form. All of the arts are being squeezed, and opera is certainly not immune, often receiving criticism for receiving the largest proportion of funding of all the major performing arts.

The quid pro quo for this support should be the consistent commissioning of new Australian work. Perhaps part of the funding could be quarantined for this purpose, as well as some judicious revivals of earlier works. It is good to see Opera Australia bringing back Brian Howard’s adaptation of Kafka’s Metamorphosis, a challenging work first seen in 1983.

One response to a lack of new opera by the larger organisations has been the growth of small companies such as Chamber Made, Sydney Chamber Opera, Pinchgut, and Victorian Opera, most of whom operate on very tight margins.

Helen Sherman (Poppea) and Jake Arditti (Nero) in Pinchgut’s 2017 production of Poppea. Brett Boardman.

The Sydney Opera House, one would like to think, will continue to present opera, but the national company, Opera Australia, is unlikely to enjoy substantially increased funding. There is always the danger of becoming a tourist attraction and not the vibrant, innovative and agenda-setting institution that it has been at times.

The opera scene in Australia might well become an entrenched two-tiered one in which the standard repertoire works, including many more musicals, with an occasional new opera, are presented by Opera Australia and the other federally-funded, state-based opera companies, sometimes in co-production, while the bulk of the new work, on a much smaller scale, will be found in the newer, small companies. (However, OA’s just-announced 2019 season certainly gives cause for renewed optimism with a new opera by Elena Katz-Chernin based on the life of artist Brett Whiteley; a William Kentridge production of Alban Berg’s 1925 masterpiece, Wozzeck; as well as performances of the renowned German composer, Aribert Reimann’s 1984 operatic version of Strindberg’s Ghost Sonata; all fascinating works.)![]()

Australia is a hybrid postcolonial society, and this hybridity is reflected in its cultural production. It is vital for the health of opera that new work is presented and revived.

Michael Halliwell, Associate Professor of Vocal Studies and Opera, University of Sydney

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.