Julian Wilton, creative director at Massive Monster, is about a day away from releasing a little game called Cult of the Lamb. I say ‘little’, but Cult of the Lamb has already received overwhelmingly positive reviews, and at the time of writing, the game is a top seller on the digital PC storefront Steam. It’s not even available to play yet – those are just pre-purchases.

Cult of the Lamb has had a remarkable pre-release marketing cycle, which built a huge swell of anticipation for the game. Impressions of a public demo released some months back were very positive. Video game content creators have been showcasing the game on Twitch to captive audiences. The merchandise – a plushie of the lamb protagonist – is adorable. The publicity stunt – a limited edition custom controller – was hideous, but it got a lot of attention.

Much of that is thanks to the game’s publisher, the publicly listed, globally-recognised ‘punk’ games label, Devolver Digital. Devolver has provided the Massive Monster team not only with veteran PR and marketing support, but other considerations and resources that would typically be outside their scope as a very small team – localisations to different markets being a key example, something that expands their potential audience greatly.

But if Massive Monster had not received early funding for Cult of the Lamb from VicScreen – formerly Film Victoria, the state government’s creative funding body – its pitch and proofs-of-concept for the game many never have impressed the likes of Devolver Digital, and Wilton would probably be telling me a very different story about development.

But here’s the kicker that gets me, especially as a resident of Sydney – Julian Wilton is originally from New South Wales, and only moved down to Melbourne a few years ago because of the Victorian government’s support for its local video game industry.

If Wilton’s home state had any kind of support for directly funding its own video game sector – which includes several aspiring developers in tertiary colleges and university courses, a few independent studios, as well as larger multinational developers – Cult of the Lamb, the latest global independent video game darling could have been the pride and joy of Sydney and New South Wales. But it’s not.

‘We love games’ was the message VicScreen was promoting at an event attended by GamesHub, held at Paper House in Melbourne, as the creative organisation showcased the work of several game developers who had received government grants for their projects.

Putting aside the big song and dance, we’ve known for a long time – through numerous conversations with Victorian game developers, as well as through the quality of games that come out of Victoria – that state government funding of independent projects is key to fostering a strong and vibrant game development community that produces excellent work.

It legitimises the creation of video games as a valuable creative industry, and Victoria has several avenues for funding and supporting game development at various stages of production, as well as other business needs.

Terry Burdak runs Paper House, the small game development studio and boutique shop that hosted the VicScreen event. Paper House previously created Paperbark, a lovely game revolving around a wombat, the Australian bush, and the perils of the hot Australian summer – funded by what was then Film Victoria. The studio’s next project is Wood & Weather, a playful god game that lets you control the weather at will, and explores the persistent effects of extreme weather caused by climate change.

Read: Aussie developer Paper House will track its environmental impact going forward

These are not the kinds of games you conjure when you think about the lucrative business of blockbuster video games, the culture of ‘gamers’, and titles that rake in millions of dollars a day. But like any creative artform, the spectrum is vast, and video games created on the independent side of the scale – like the ones funded by VicScreen – are incredibly valuable. They use the medium to explore the kinds of ideas and stories that the biggest developers would never dare to touch, and in innovative ways that are rarely explored.

According to Burdak, though Paper House is largely run off the studio’s own back, VicScreen funding has helped to greatly minimise the studio’s financial risk drastically, providing more security for its creatives, which then allows the team to pour more energy into their creative work. ‘I’ve been able to make sure everyone (including myself) has moved from being contractors to actual employees, and all the benefits that come from that like sick and annual leave, and get[ting] super’, he says.

A similar story comes from Guck, a relatively new First Peoples-led studio working on Future Folklore, a farming management game for mobile devices with a futuristic fantasy setting inspired by the Australian bush. Project director Hayley Percy, a Wiradjuri woman, says that the company has greatly benefited from VicScreen funding, especially since they’ve been putting a strong emphasis on going above and beyond to build out their team in a way that places Indigenous people in key positions throughout every facet of the company. Guck is currently feeling out the absolute best practices to implement this, in what Percy refers to as ‘building a substantial foundation of sustainability.’

‘The things that we’re dedicated to are actually setting some different foundational practices in the industry,’ says Percy. She says that having the breathing room to build this has been key. ‘We need to give people the opportunity to build their skill set, and not assume everyone needs to be a top gun in their roles, because that’s not how you build diversity in the industry. It has to start from the ground up.’

That approach is a beneficial one for anyone operating in the industry. But Guck’s exploration into this new territory will hopefully also pave the way for how First Peoples are able to participate in the Australian games industry in the future. Percy cited things like understanding how First Peoples might operate differently as a creative team, how there might be differences in how they work with funding bodies and other organisations – and Guck’s hope is that it can filter an understanding of best practices elsewhere in the screen industry.

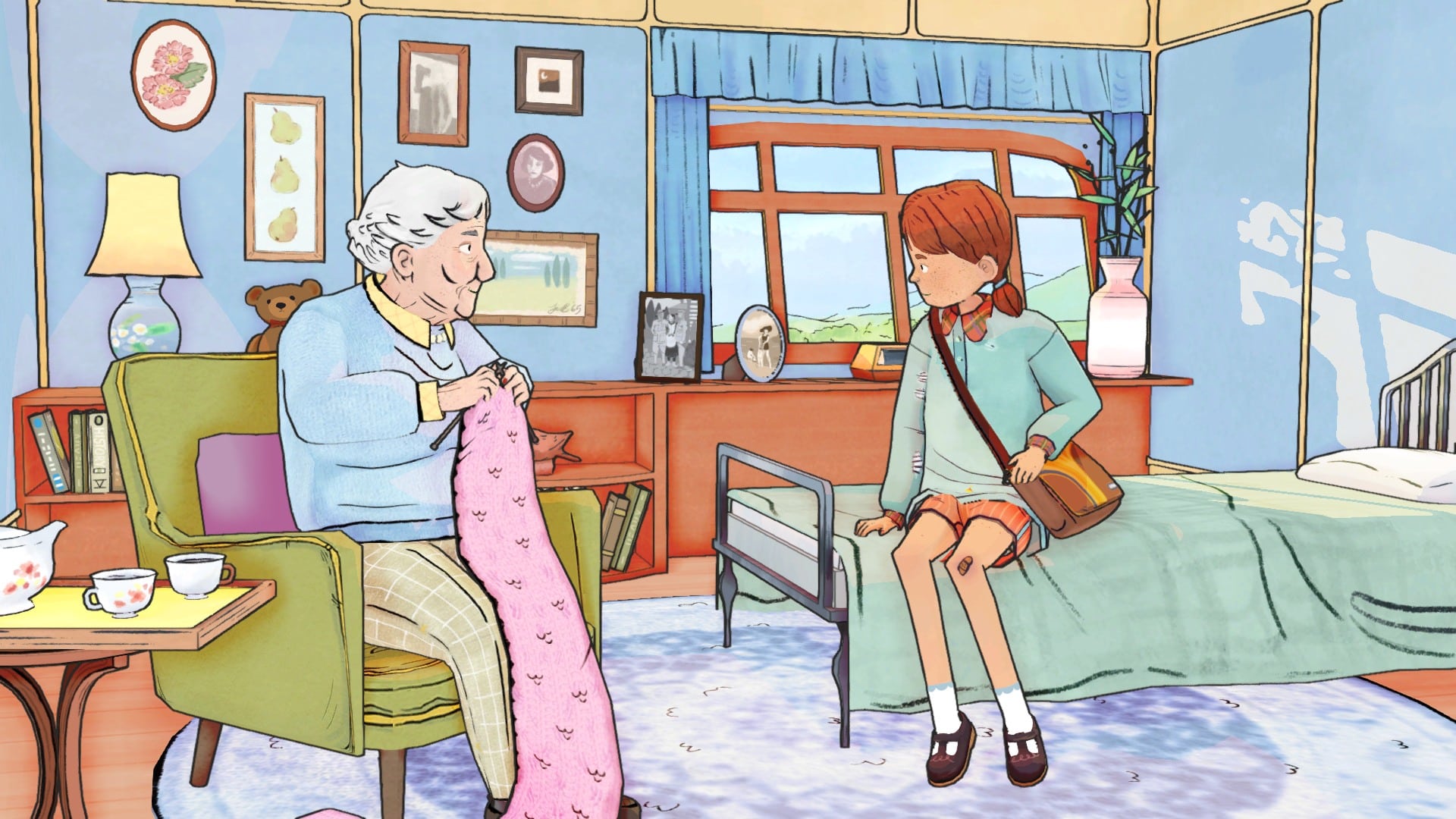

Wayward Strand from studio Ghost Pattern has long been in the eye of the local games community – it’s a unique narrative game set in 1970s rural Australia that explores aged care through the lens of a pre-teen girl, which uses principles of spatial theatre to put the storytelling onus on the player.

Victorian state government grants have helped the Ghost Pattern team at every stage of the journey, says Jason Bakker, and that consistency has ensured the game’s distinctive approach to exploring deeper themes has been well-resourced and supported, long-term.

Wayward Strand was actually one of the first games VicScreen funded a prototype of, according to audio director Maize Wallin – something that has since become standard practice. Now, over 6 years and 30 collaborators later, Wayward Strand is on the eve of its release in September 2022. It features an incredibly strong Australian voice cast, including screen veterans like Michael Caton and Anne Charleston, in a piece of work that incorporates game, film, and theatre elements to create a very special identity for itself.

In that same period of time, Anthony Tan has been working on Way to the Woods, a game that follows a deer and its child through a magical-realist post-apocalypse. Tan began work on Way to the Woods when he was only 16, and the game quickly drew attention for its striking visuals and animation. A trailer that debuted at an Xbox press conference in 2019 caused interest in his passion project to skyrocket, along with expectations for the game.

Tan’s public communication more or less ceased in 2020, as he looked to refocus the game’s direction and reconsider everything about the project in the wake of its sudden popularity – he was, after all, still just learning how to make his first game – and as anyone would expect, creating something on your own is hard enough without the weight of great expectation.

Tan had received some initial grants from commercial entities like Microsoft and Epic Games, but it was only just enough to keep him afloat as a solo developer for so long. Tan was the recipient of VicScreen funding in early 2022, which he says has been key in getting Way to the Woods over the finish line, and improving the quality of his working life – which will hopefully feed back into the quality of the game. Now aged 23, he’s been able to move on from working out of his bedroom and in Melbourne’s State Library, to inhabiting a coworking space at ACMI X. This move allowed him to better connect with other game developers and creatives in Melbourne’s community, and catch a bit of sun, too.

All of these stories suggest the same thing: if a government truly cares about its creative arts – of which video games are one of the biggest and most widely appreciated – it needs to go out of its way to specifically fund the small, independent games creators that are vital to the continuation of the industry.

Victoria has been doing it consistently for around 30 years – through Film Victoria and now VicScreen – helping Melbourne become globally recognised as one of the cities where some of the most celebrated games in the world are made. Over half of Australia’s game development efforts are located in Melbourne, and if people like Julian Wilton are any indication, it’s where all the upcoming talent is going to end up.

Screen Queensland has followed suit in an effort to bolster its industry. Screen Australia has implemented similar measures at a federal level, to complement the Digital Games Tax Offset.

Now is the time for a wake-up call to the rest of Australia’s states and territories – and other countries and regions around the world – to develop (or in some cases, resurrect) the games funding programs that will ensure the country is making the most of the increasing global interest in the games sector – and, to ensure we’re tangibly supporting the talented developers who can bring great art into the world with video games.

Disclaimer: GamesHub travelled to Melbourne, Victoria on behalf of VicScreen for the purposes of covering this event.