Many would argue that Robert MacPherson has been a pivotal figure in Australian art since the 1970s, having influenced a generation of artists with his conceptual paintings and multi-panel installations that pull apart perceptions of what painting is, and can be.

Born in Brisbane in 1937, he has passed away on 12 November in his home town aged 84, following a brief illness.

His 40-year career delved – relentlessly – into what constitutes a work of art, often incorporating everyday materials and signage from daily life. For him the mundane was inspirational.

Art historian Rex Butler reflected in a 2015 issue of Artforum, on the occasion of MacPherson’s major survey exhibition: ‘MacPherson’s art is leavened by a humour we might ultimately want to call Australian … self-deprecating, egalitarian, born of a sense of distance from established cultural centres and a feeling that one will never belong.’

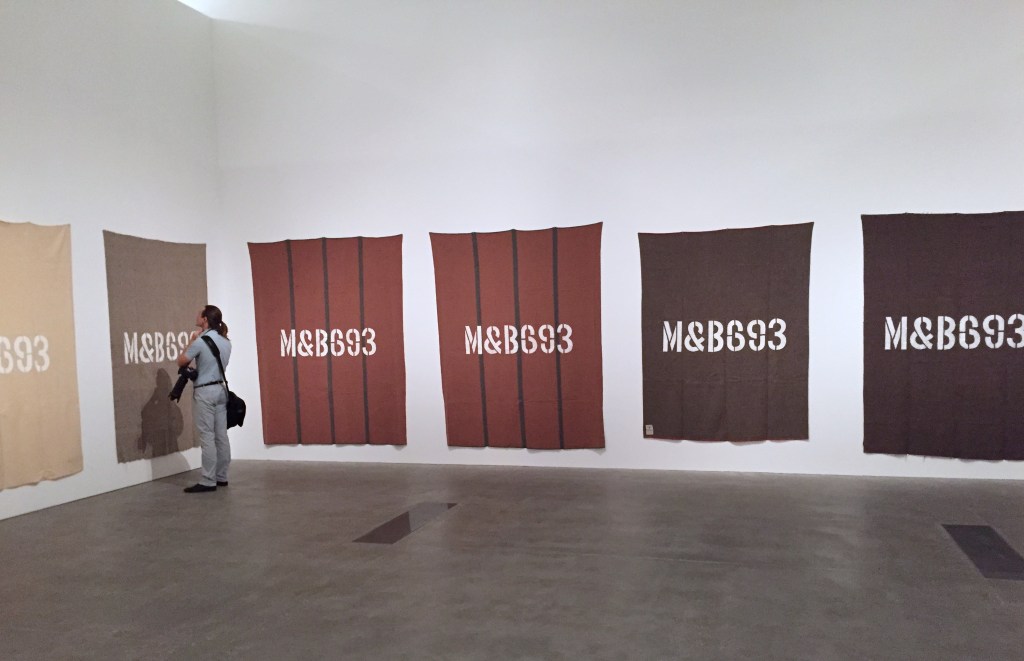

MacPherson is perhaps most recognised for his text-based works, which fell into a lineage from minimalist to Fluxus thinking through to the conceptual. In other words, the casualness of the appearance of much of MacPherson’s work masked his deep rigour for art history and contemporary making.

However, MacPherson was a self-taught artist. As writer Andrew Frost described, he was ‘more interested in exploring ideas and connections than explaining them.’

He had a huge grasp and knowledge of the world, fascinated by social history, by mythology and biology.

His fascination with creative expression started as a teen. Dropping out of school, he worked in a cannery, then on a cattle station, cutting cane and painting ships – a kind of hopscotching across jobs that kept him grounded to a reality that seeped into his art.

‘This connection to the world outside the gallery became emphatic with the artist’s later excursions into vernacular sign painting,’ writes Dr Tara McDowell, Associate Professor and Director of Curatorial Practice at Monash University, Melbourne.

MacPherson enrolled in art school in 1961, aged 24, but lasted only a week. He found his art education at the local library, and by looking.

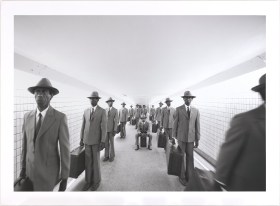

He had his first solo show in 1973, presenting a suite of pared-down black and white paintings. It was to become a signature that stayed with him for his entire career – evident in MacPherson’s retrospective The Painter’s Reach, curated by Ingrid Perez for QAGOMA (Queensland Art Gallery / Gallery of Modern Art) in 2015.

And in 1975, MacPherson had his second solo exhibition (aged 38) at the newly opened Institute of Modern Art (IMA) in Brisbane, where he showed a series of 4-panel paintings. His statement from that show reads like a manifesto:

‘An awareness of modern art history, a belief that all good art comes from previous art, my rules are formed within this context. An awareness of the means. I have no wish to subvert the means, the rectangle or negate the object. Juxtapositioning of means (surface, handling and ground) is content. My work makes no assumption beyond itself – then you have response, and that’s another story. An awareness of formal principles remains. Things happen in process and are left; I am surprised.’

He was proposing a form of Australian Dadaist poetry through a visual expression.

A further turning point was his inclusion in the 1979 Biennale of Sydney (its third edition) and over the years he would be included in subsequent editions, and other biennales such as Sharjah Biennial and Culturgest Contemporary Art, Lisbon.

But MacPherson’s work was not just about the vernacular of found signs; he was like a bowerbird taking from the everyday – dry cleaning receipts, typed sheets of paper with didactic descriptions of what it is you’re looking at (or not looking at), works using wool blankets and text.

This passion of expression through ‘things’ is further testament in a long-running swap of mail art with fellow Australian artist Peter Tyndall – who donated the items he had received from MacPherson (numbering around 13,000) to the Queensland Gallery Art Research Library in 2014.

MAPHERSON’S WORK

We all have our favourites among MacPherson’s works – images that are indelibly imprinted in our Australian psyche.

Perhaps it is his Duchamp-esque Three Paintings (1981), which consists of three paintbrushes mounted to a wall, or the series Frog Poems (1982–), which pairs various prosaic objects with the Latin names of assorted frog species, or it might be I See a Can of Paint as a Painting Unpainted, comprised of a chair, a pile of photocopies, and a four-litre can of paint.

Or perhaps your signature for MacPherson rests with his signs, and the gargantuan installation Chitters: A Wheelbarrow for Richard – 156 paintings / signs – black-on-white texts.

A work that has particular resonance for many is an early work, Scale from the Tool (1976), a suite of vertical canvases painted to varying degrees.

Art critic Andrew Frost described it: ‘The result looks calligraphic but it’s also conceptual: the painting looks this way because that’s what a brush and paint can do when used within strict limitations.’

It was that very capacity to distil not only the world around us, but the annals of art history, enmeshed and presented as a kid of haiku – allowing humour to rub shoulders with the rigours of conceptual art.

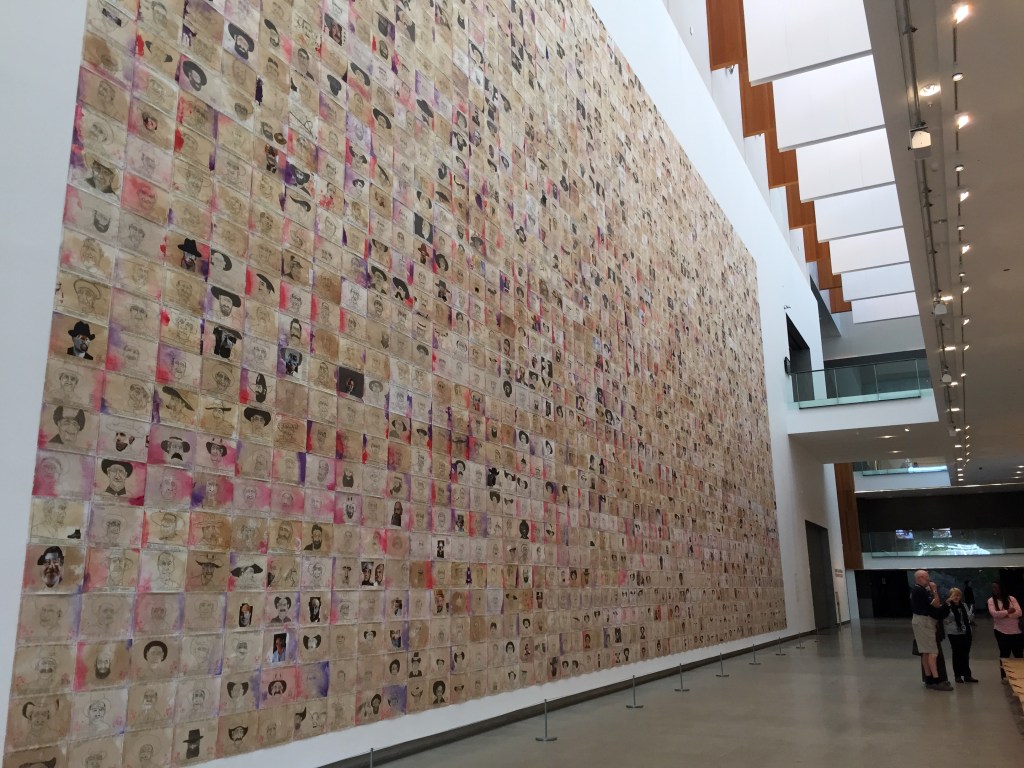

In a curiosity, MacPherson decided to take on an alternate artistic identity – Robert Pene – sharing a birthday with MacPherson, but eternally a mere lad of around 10 years.

Pene has dated all his works 14 February 1947. While these works have dotted his oeuvre, of note was the mammoth series of 2,400 drawings of imaginary ‘boss drovers’ which filled the atrium of GOMA for his survey.

MacPherson’s art is held in the numerous collections including Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney; Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide; Fremantle Arts Centre, Fremantle; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra; and National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, QAGOMA in Brisbane and the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, among many others.