Please note this article includes references and links to violence, including genocide, suicide and torture.

Darkness. Perhaps no other state carries as much weighty spiritual connotation – death and grief, violence and evil, the shadows of the unknown and the unknowable. Yet we find ourselves in darkness every day, a cycle almost as immutable as that of breathing.

Similar tensions characterise the medium of photography. Commonly understood as an art form of light (the photo- prefix itself establishes this primacy), photography nonetheless relies equally on darkness. Culturally, photography’s revelatory and representational possibilities are widely championed, but what of the medium’s capacity for violence?

The Centre for Contemporary Photography (CCP)’s new exhibition, Walking Through the Darkness, seeks to grapple with the paradoxes of darkness in ways both technical and thematic. The exhibition brings together a group exhibition of 16 Australian and international artists at various stages of their practice.

It’s uncommon to see big names such as Todd Hido and Rinko Kawauchi alongside lesser known Australian artists – something CCP Curator Catlin Langford is passionate about remedying.

‘Part of our mission at CCP is also to place emerging and established Australian artists in dialogue with international artists. Simply by the sheer fact of distance, this does not occur as often as it should given the brilliant talent coming out of Australia, so we see CCP as a space to allow for these dialogues to take place,’ Langford tells ArtsHub.

For Melburnians drawn to photography, CCP, located in Fitzroy, is an undeniable boon – an expansive space showing local and international artists from emerging to world-renowned. The space is wheelchair-accessible and entry is by gold coin donation, with free and thoughtfully programmed events throughout the year.

The works of Walking Through the Darkness explore death and grief, abandoned places and haunted landscapes, violations of body and culture, relationships with animals, and manifestations of the sacred in the everyday. Artist Renato Colangelo’s site-specific installation, Dark Chamber, allows viewers to enter a camera obscura, inviting a (literal) new perspective on the mechanics and history of image-making.

The exhibition’s photographic and video works are visually striking, and the dialogue between them is rich. Amos Gebhardt’s x-ray images of injured Australian fauna evoke not only brutality but the presence of stardust, and Morganna Magee’s exquisite images of animals are also suffused with the vulnerability of contact with human environments.

Magee made these images as part of a series she has named Extraordinary Experiences, referencing a period of intense grief during which she had a series of epiphanic encounters with her surroundings. Grief, too, permeates the works of Seiichi Furuya, which chronicle his and his late wife’s ritual of making simultaneous images of one another, a series of tender portraits rendered heavy by the knowledge of her eventual suicide.

A meeting of the quotidian and the alien connects the works of US photographer Todd Hido, his house exteriors lit up against stark landscapes, and Li Yang, whose photographs document the Chinese nuclear research town in which he was born. The town is now abandoned and known only by a number: 404, aka ‘Not Found’.

Chloe Dewe Mathews juxtaposes scrawled text from Mary Shelley’s initial drafts of Frankenstein with the beautiful yet austere Swiss landscape that inspired them. The disused nuclear bunkers of Dewe Mathews’s Swiss Alps are, like Yang’s works, haunted by the spectre of nuclear threat.

The cumulative effect of the works is dark, yes, but also strangely holy – the feeling of all pageantry having been stripped away.

History’s ghosts

On one gallery wall’s surface, a floor-to-ceiling image draws the eye: a gleaming, almost holographic machete embedded in a tree stump. It sits in a clearing surrounded by dense foliage.

This is the work of Buzz Gardiner, a Vanuatu-born Australian Solomon Islander artist now living on the Gold Coast. During the pandemic, when the islands closed their borders, he found himself confined to Australia and seeking out spaces that offered a sense of home.

From his series Banyan Coast, the place depicted in Clearing reminded him of spaces in which he played as a child, but the pull felt deeper than that. Gardiner became interested in the site as a place of connection, a possible link to a time when Pacific Islanders – most of whom were from Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands – were rounded up and transported as slave labour to Australia under a colonial practice known as ‘blackbirding’.

Eventually deported in large numbers due to racist policy, Pacific Islanders’ connections to sites like these are largely obscured. Gardiner is careful to situate himself within the nuance of this subject, noting that he doesn’t identify as South Sea Islander, a distinction that informs what is and isn’t represented in the work. Nonetheless, he believes the history of blackbirding deserves attention.

‘It is very much a history that largely exists in the dark,’ says Gardiner. ‘When the person in charge of the country is unaware of the practice (shout-out to former Prime Minister Scott Morrison), I don’t think it’s unreasonable to say blackbirding is not as widely known as it should be. By shining a light on this history, we then see how South Sea Islanders came to be.’

The machete in the image (called a “bush knife” in the islands) is an archival image from the Pacific and, by digitally planting it in a very real place, he reimagines this connection.

A witness

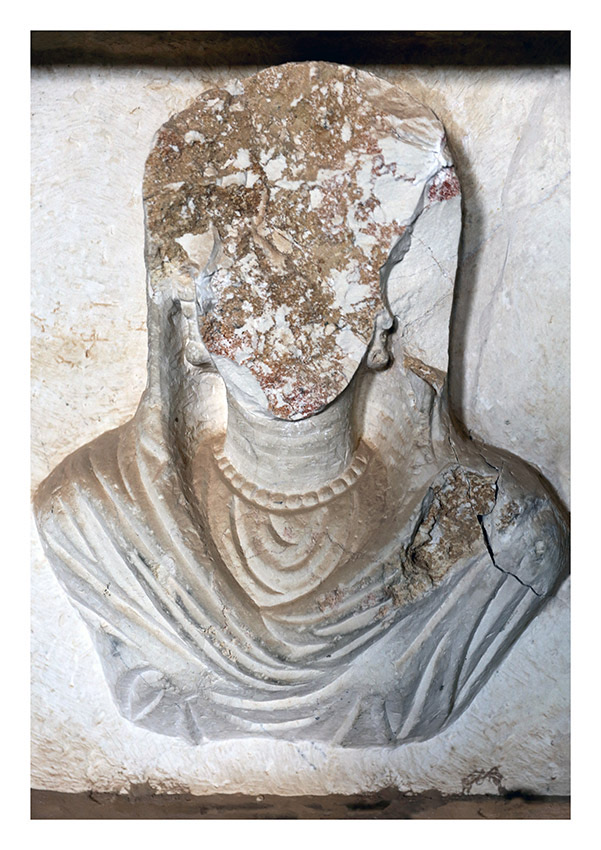

There are pictures of Middle Eastern stone artefacts, mostly depicting people, all with their faces caved in by force. Some have been partially restored, and the result is an inadvertent Picasso-like Cubist reassembly – forces of dark and light at work.

Fassih Keiso is an Australian Syrian artist who visited the ancient city of Palmyra in Syria. The city was captured by, then liberated from, ISIS. He set about documenting the historical shifts, including the damage to artefacts caused by archaeological violence. He completed the series Iconoclasm after three visits to the city’s museum. The first was only days after the Syrian Government first reclaimed Palmyra from ISIS, and the most recent was in February of this year.

Keiso tells ArtsHub: ‘[D]amaged historical busts and other architectural ephemera are transformed into art objects while also reflecting the material realities and political contexts of mass cultural harm. The shattered faces of the busts, along with their hereditary location and geographical significance, provides us with a sensibility of cultural violence and chaos.’

In the main exhibition space, Keiso’s work sits adjacent to the work of Rushdi Anwar, which references the 1988 chemical attack on Anwar’s home city of Halabja in Kurdistan by the Saddam Hussein regime. In the smaller gallery space, Israel-born London-based photographer Ori Gersht’s video depicts falling trees in a forest, posing questions of memorialisation and collective memory in relation to the Holocaust. Though differing in materiality and presentation, all three are powerfully in conversation about the act of witnessing.

A thousand cuts

It’s easy to assume, when looking at a photo, that what’s depicted is incontrovertible fact, straightforward in its interpretation. Darren Tanny Tan, a Singapore-born, Australia-based artist, isn’t so sure.

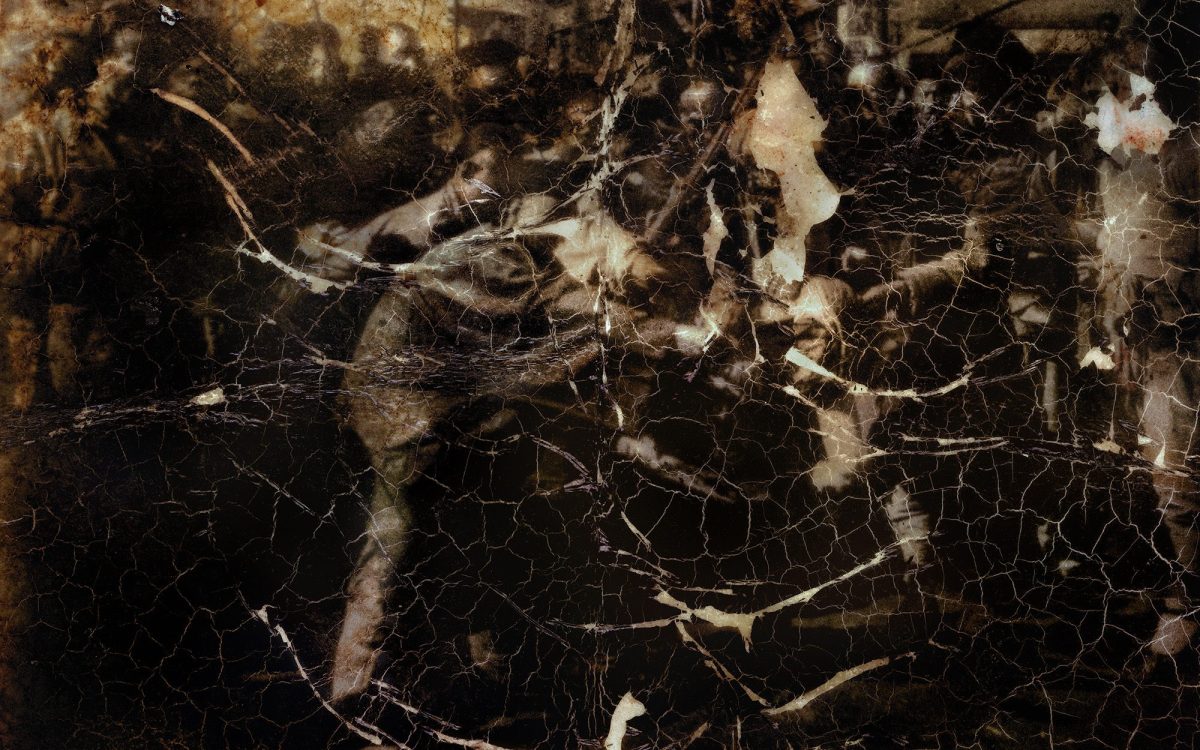

Since moving away from the traditional use of the camera in his practice, Tanny Tan’s works have become increasingly concerned with the notion of representation. The series By A Thousand Cuts is his first substantial body of work that centres on the use of historical images, which are reworked in a way that obscures much of their content. The result is a gradual apprehension – from afar they look somewhat like aerial land photographs taken at night, but upon closer inspection, reveal themselves to contain faces and bodies.

This obscuration is deliberate. Tanny Tan is troubled by what he describes as the ‘inherent indexicality’ of photographs, and their inability to fully represent history. The lingchi photographs, which depict an extreme form of capital punishment practised in China until early last century, cannot explain the complex social and cultural conditions that gave rise to the practice, or the images’ making.

The original lingchi images, taken by French soldiers stationed in China, were circulated in the West on postcards as what Tanny Tan calls ‘titillating curiosities’. Indeed, even the title of the series is a nod to misrepresentation. In the West, lingchi is known as “death by a thousand cuts”, though this does not accurately describe the practice.

Tanny Tan says: ‘This vexed relationship – the photograph as evidence of the past, and paradoxically, its failure to fully represent history – becomes the point of interrogation in this body of work. Reworking the lingchi photographs thus serves two main purposes: to lessen the horror such that they can become images to be contemplated on and, almost in a literal sense, to highlight the gaps in our understanding of historical events. In that view, the works are as much about deconstructing notions of history as they are about shining a light on the past.’

Read: Remote Indigenous artists zooming in on photography

What are we looking at?

Writer and photographer Teju Cole wrote in What Does It Mean to Look at This?, ‘Photography works and it doesn’t work, it is tolerable and intolerable…’

When people, places and phenomena are frozen in time, what are they reduced to, and for what end? For a photography exhibition about darkness, it would have been powerful – and exciting – to see more artists featured whose work contains an essential ambivalence about the role of photography – about what it can’t see, can’t convey, can’t overcome. As Tanny Tan puts it: ‘The ontological insufficiency of image.’ His work is in this sense striking and important, but it reaches out into the space for a conversation that doesn’t quite seem to materialise.

Violence has long been a byproduct of photography, and at times even an aim. The exhibition would perhaps also have been enriched by the perspectives of Black and Australian First Nations artists, whose communities know firsthand the effects of photography as a tool of violence – upholding the colonial urge to know, to categorise and to frame according to its own troubling logic. Can this darkness be transmuted or reclaimed? Perhaps CCP’s next exhibition, a solo show of works by James Tylor, will continue the conversation.

Overall, Walking Through the Darkness is an exhibition worth seeing, maybe even twice.

Walking Through the Darkness is open until 10 September at Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne, with several events and talks programmed over the remaining days.

This article is published under the Amplify Collective, an initiative supported by The Walkley Foundation and made possible through funding from the Meta Australian News Fund.