Pablo Picasso, Minotaure caressant une dormeuse. [Minotaur caressing a sleeping woman.], from the Vollard Suite (93), 18 June 1933, plate reworked probably at the end of 1934, drypoint; Purchased 1984, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

With time attitudes change, and art is not benign to that shift in what might be deemed socially acceptable or appropriate. The Vollard Suite – Pablo Picasso’s great masterworks in printmaking – is a good example.

Picasso’s name guarantees people’s interest and aesthetic respect, and yet, some of the images in The Vollard Suite are what we might regard today as no longer “politically correct” or simple just offensive – they depict images of female domination, of rape, and psychological devouring of women.

The National Gallery of Australia is one of the few cultural institutions in the world to hold the complete suite of 100 prints, and it is currently touring the work. It was presented by the Queensland Art Gallery last year, is currently showing at the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA) and will next visit the Art Gallery of Ballarat, before returning to Canberra.

The Vollard Suite comprises etchings, engravings and aquatints created by the artist in the 1930s and is named after Ambroise Vollard, Picasso’s art dealer and publisher. It contains several themes including Pygmalion, an artist obsessed with his model, and the mythical figure of the Minotaur – half man/half beast that is transformed from gentle lover and bon vivant into a rapist and dominator – reflecting Picasso’s turbulent relationships with his mistress Marie-Thérèse and wife Olga.

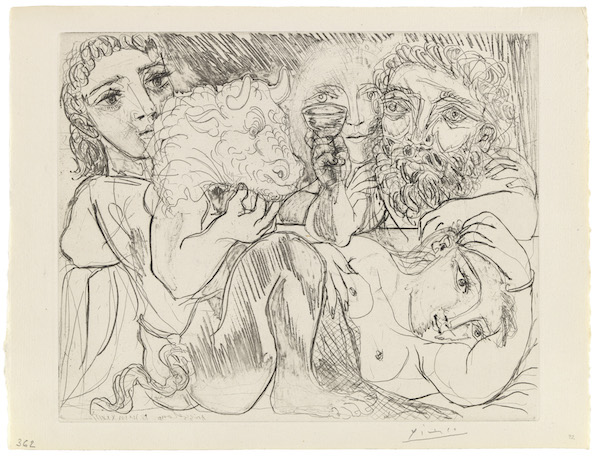

Pablo Picasso, Minotaure, buveur et femmes. [Minotaur, man drinking and women.], from the Vollard Suite (92), 18 June 1933, plate reworked probably at the end of 1934, drypoint, etching, scraper and burin engraving; Purchased 1984, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

AGSA Associate Curator of Prints, Drawings and Photographs, Maria Zagala was not content to just put these prints on the wall. She told ArtsHub: ‘I have always admired the prints but this time, seeing them in 2018 when I started working on the show, I was very aware that the context in how we look at them had shifted.’

She continued: ‘As a touring show from the NGA it came as a package with labels and layout. I approached Sally Foster (who had prepared the tour) and asked whether she would you be open to changing some of the wall text and building into the exhibition an interpretive framework for how these prints are being received now.’

Zagala said that she had been moved by Hannah Gadsby film Nanette.

‘I am in this privileged position of a curator working today and have the job of presenting this exhibition. I felt it was my responsibility to take into account what she had said, and to respond to this cultural shift that is happening with the rise of the #MeToo movement,’ said Zagala.

She added that there are no easy answers. ‘What are the ethical ways of responding to criticism of art and artists made of another time, and our role as an institution if an how we show that? It is really hard to answer, and partly because the works are incredible, but with time the works are so disturbing.’

‘What is shocking in the series is that depicts rape outright. I can’t think of a precedent in print or art history that depicts so without the distancing mechanism of mythology,’ she added. ‘There are five images in the suite – and they are very uncomfortable.’

John William Waterhouse’s painting Hylas and the Nymphs was taken down by Manchester Art Gallery. Photograph: Manchester City Gallerie

Is greatness a valid excuse for acceptance?

‘I am glad these works are being shown at museums and galleries; it would be far worse to censor them,’ said Zagala.

In February last year, Manchester Art Gallery removed a painting by John William Waterhouse, Hylas and the Nymphs (1896), which depicts Hercules’ male lover Hylas being lured to his death in a pond by topless nymphs. Postcards of the painting were also removed from sale in the gallery’s shop.

Clare Gannaway, the gallery’s curator of contemporary art, told The Guardian the aim of the removal was to provoke debate, not to censor. ‘It wasn’t about denying the existence of particular artworks.’ Waterhouse’s painting is one of the most recognisable of the pre-Raphaelite paintings.

It was replaced with a notice explaining its removal was ‘to prompt conversations about how we display and interpret artworks’. Members of the public stuck post-it notes around the notice in response. It lasted only a couple of week’s until the backlash reached ridicule and the painting was returned.

Balthus, Thérese Dreaming (1938), Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A similar situation occurred in the United States, when a woman led a petition against the display of the Balthus painting Thérèse Dreaming (1938) at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, saying that it ‘romanticises the sexualisation of a child’. The gallery chose not to remove the work. Similarly, in Australia Donald Friend’s work has been under scrutiny, and at times removed from exhibition.

Zagala reported that over 10,000 people have visited The Vollard Suite in December alone.

‘I feel that there is something disconcerting exerting social change in the way we are, and in public discourse especially around consent. Just the discussion of Picasso as a genius as justification is not that helpful really, and just comes down to attacking the work misogynist geniuses. What is helpful is the encounter with the work and trying to understand what happening in work and in us when we view it,’ said Zagala.

She believes that art museums do have a responsibility to show this material rather than leave it in their basements for scholars alone.

‘Should art galleries show works that depict rape? I see The Vollard Suite as one work in a hundred parts and it is hard to isolate individual prints. The suite is dizzyingly brilliant. I think approaching it – in way done here – with reading list and giving people the opportunity to read about various perspectives, not condemning nor praising Picasso, but presenting work in the present is the way forward.’

Dialogue is part of understanding

There is interesting writing that happening today in different fields that has emerged from the #metoo movement, whether political analysis economic or cultural analysis, it is dialogue that Zagala says, ‘as a museum worker – a curator – brings with it a certain pressure to define what is happening. It is our responsibility to shape it.’

Her response was to build a public program around the exhibition, and to provide visitors with a reading list.

‘Online we have put a short essay with a number of references, ranging from art historical texts, to artists to blog posts, to Picasso to contemporary responses,’ said Zagala. She also pointed to American professor, Memory Holloway, who published a very nuanced reading on the suite in the 1980s.

Maria Zagala will be in conversation with Meaghan Morris, Professor of Gender and Cultural Studies at the University of Sydney on Friday, 1 February at 6pm, as they discuss on the impact of the #MeToo movement and the contemporary reception of Picasso’s practice.

They will be joined by video with Emerita Professor Memory Holloway from the Department of Art History, University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth.

You will also be able to enjoy live music by Sunitra Martinelli from Mélange à Trois, who will be accompanied by a power house of women to perform in celebration of our First Friday theme, Grabbing the bull by the horns: experiencing Picasso’s Vollard Suite.

Touring from the National Gallery of Australia

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Until 3 February 2019

Art Gallery of Ballarat

23 February 2019 – 28 April 2019