Queer and Present Danger is a three-part series written in response to the cancellation of queer events across 2023. Many a battle has been won but, as this year has shown us, glory and progress are fragile and easily stripped away.

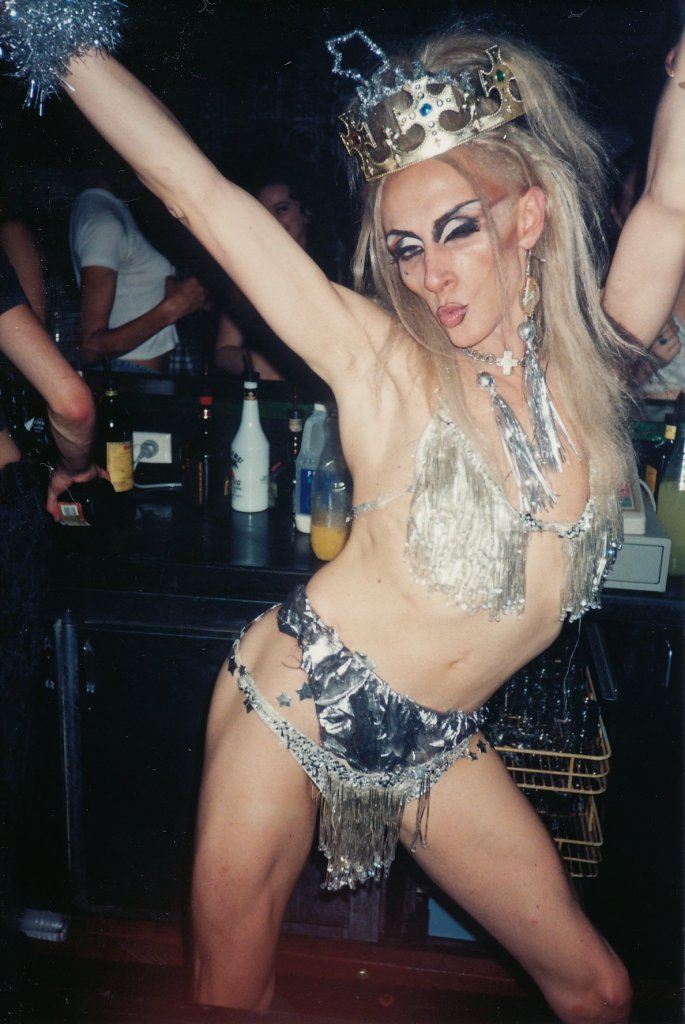

More than mere performers, drag queens are and always will be the Rainbow Communities’ matriarchs – staunch protectors in glamorous, bejewelled armoury and a killer set of heels. This is Australian drag across four decades, told by those that tread the boards.

A tale of two cities

The year is 1979 and in the state of New South Wales homosexuality is still a criminal offence that carries terms of imprisonment… It’s only a year ago since the Sydney community took to the streets in the first Mardi Gras and, in a protest met by police brutality, said that “enough was enough”.

Across the following decade, a string of gay hate crimes and murders will continue to be committed across the city’s North Shore. Another five years of advocacy will ensue before the Neville Wran Government introduces a private member’s bill that will lead to the decriminalisation of homosexuality in NSW.

For now, there is not so much as a rumble of an even greater battle that will claim many lives – young and old – looming just on the horizon.

This time, however dark, carries a folkloric quality that will set the scene for the broader push for equality across Australia in decades to come.

Against this backdrop, the career of one of Australia’s most iconic drag queens, Cindy Pastel, emerges. Pastel has continued to pave the way for those that have followed.

Pastel’s story

Born and bred in the Melbourne suburb of Ascot Vale, Pastel travelled to Sydney ‘just to see what all the fuss was about with marching and riots’. She was barely 20 years old and ‘cute as a button’, Pastel recalls, adding in her usual foul-mouthed style that ‘she was instantly welcomed with open legs and was never knocked back’.

Despite losing a talent competition one fateful night in 1979 at Patchs Disco, Pastel tells ArtsHub they ‘weren’t dreadful’.

‘I scored a five-night stint at Patchs Disco on Oxford Street,’ says Pastel. The rest, as they say, is history. Before long Pastel had befriended the door bitch who was soon to be the mother of Pastel’s child.

‘Trixie Lamont was the top dog drag queen at the time and decided to have a betting pool on what sex the baby would be. We had a baby shower across the road at The Exchange Hotel… It was a free-spirited time. Alas, we were unready for the somewhat heady and depressing future ahead.’

It was in 1983 that those first rumblings of the AIDS crisis were felt.

During the ensuing years, Pastel would start shows by asking ‘is everybody happy?’ she recalls. ‘As sad as we all were, losing dearest friends, I always got a “yes!” We blundered our way through AIDS.’ Pausing for a moment, Pastel adds, ‘These are some of my proudest moments ever in my life – through drag we all still found a way to laugh.’

In 1985, just a few years after Pastel’s career had started to take off, it nearly ended when a fall from the stage left her in hospital with a cerebral haemorrhage and in a coma.

‘My son was only four months old at the time,’ Pastel says. ‘The merry-go-round of drag stopped spinning and I was left a mere part of my usual self. I got off that ride and became sober. I still walk on my tiptoes, but haven’t had a bevy since 1999.’

Following this, Pastel – believing she was not as funny sober – ‘gave up performing and just by chance took it up again after a nearly 10-year break’.

‘And before you ask, yes, it really is just like riding a bike.

‘By then I had become known as the “bisexual” drag queen. So, I thought, “OK… I am proud to be me, nothing else matters.” To this day I have strangers thank me for coming out (hopping back in) and out again! It’s been a bumpy ride.’

Pastel, who turns 66 this month, hopes she ‘still does people proud’. Which according to fellow drag queen Vanessa Wagner, she most certainly does.

Born in the same era, and emerging against the broader and much darker backdrop that was Sydney in the 1980s, Wagner says Pastel’s star always shone brightly.

Speaking with ArtsHub, Wagner remembers seeing Pastel performing for the first time in 1984 at Ruby Red’s on Crown Street in the inner Sydney suburb of Darlinghurst. ‘It wasn’t just the madcap vibe of performance, but when she got on the mic it was raw and unedited. She captivated me from that point onwards,’ says Wagner.

‘Ninety percent of the drag I saw at the time was an endurance exercise for the audience, you know, just for us to get a drink from the bar. Pastel was something different, something I was actually interested in.

‘The coppers were demonstrably rough and disgusting, particularly before decriminalisation. But Sydney was still raw, you could afford to live on the dole. There was so much going on at the time, mad people.

‘I mean, I have a million stories about Pastel…’

Operation Maze

As the curtain drew on the 1980s the influence of Pastel’s drag sensibilities was about to tip over into the mainstream. And if her story seems more than a little familiar, it should. For Pastel was immortalised as the inspiration for Hugo Weaving’s character “Tick” Belrose, aka Mitzi Del Bra, in the seminal Australian film The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of The Desert.

Premiering in Australia on 8 September 1994, the film is a powerful and not altogether quiet depiction of Australian attitudes outside the supposedly safe harbours of its inner cities.

Just a month prior, one of those safe harbours had been stormed by authorities in Melbourne.

Operation Maze was a targeted attack on the queer community, when at 2.10am on Sunday 7 August 1994 around 40 members of the Victorian police in full riot gear raided the Tasty nightclub. Before the sun had risen, all 463 patrons had been unlawfully detained, strip searched in public view and for up to seven hours were provided with no information.

Remembering that night, drag queen Sarah Pax tells ArtsHub there were already rumblings that the raid was imminent. ‘We had gay policemen friends who came in as patrons, and through those and other certain channels we knew it was coming,’ she says.

‘Among all the organised crime going on in Melbourne, us f**s were an easier target for the cops. Or so they thought. For about three weeks we knew it could happen, never imagining what that would actually mean, the seriousness of it.’

Read: Queer culture is under attack: fighting back

Pax, an internationally regarded drag queen, was thrilled to get a job at Tasty as the barmaid in drag. ‘I loved it because I got to meet so many great people,’ she says.

‘What I loved most was I got to look after the trans people and the drag queens. I always had drink cards, so I could treat them well and get to know “the girls” that way,’ Pax explains.

Like Pastel, Pax performed her first show at Patch’s in Sydney in 1980 at the tender age of 13. Then, just six years later, Pax left Australia to travel around the world doing drag, before returning to home soil in 1994 with Penny Arcade’s hit show, Bitch! Dyke! Faghag! Whore!

‘When I first came to Melbourne it was known that police would stop you for stupid reasons and ask for your ID. I always thought they could go f**k themselves, but if you spoke like that, you would quickly find yourself arrested,’ says Pax.

‘AIDS had hit Sydney pretty badly when I left in 1986 with a lot of friends getting sick. But I spent most of the crisis in the US. When I came back seven years later, my personal grief was not only about missing and losing so many friends, it was also seeing how all my mates who had survived were affected. I could see it in their faces and in their souls.’

Hands against the wall!

Returning to those fateful hours on 7 August 1994, Pax describes it as starting off as ‘just an ordinary night’.

‘I was behind the bar when the music stopped. When it didn’t come back on, the news reached from the front of the club to the bar very quickly. No one was aware of what was going to happen. We had no idea what was coming and as it unfolded the lower jaw just kept dropping and dropping and dropping.’

Pax and fellow bar staff were the last to be searched. For seven hours they were made to stand in one position, with their hands on their heads, witnessing first-hand the brutality and “unpreparedness” of Victoria Police play out in real time.

The time it took the police to execute the raid was, according to Pax, as much down to that unpreparedness as it was to police tactics. Not understanding Tasty’s mixed clientele or the diversity of queer spaces, they had from the outset thought it adequate to provide only one female officer to search around 150 female patrons, a third of the entire crowd.

The situation was worse for trans and gender diverse patrons as the police were unsure of ‘how to handle them’.

‘By the time it came for us to get strip searched, they had it down pat,’ recalls Pax. ‘The bartenders were all herded into other groups of punters. I was taken into the piss troughs. In full drag and in front of other people, I was told to take my shoes and socks off, strip, bend over and to “part my cheeks”.

‘The officers weren’t changing gloves between searches and a number of patrons were up in arms over this because we were across the law, our rights and, of course, the health messages of the past decade.’

TV dinners with a side of the subversive

‘It was so strange a couple of nights later sitting in front of TV with the flu – because a lot of people got sick after the raid – seeing it on the news was an amazing trip. The talk about how the cops f***ed up, the talk about our civil rights. From thereon in it just became history.

‘It was camp, our deviant little member-only club is now on the news and being watched by people in Ballarat and Bendigo as they eat their TV dinners.

‘This period of time was also about changing what we would accept, and talk about us possibly having rights. This moment was our Stonewall,’ adds Pax.

‘I think the importance of drag shows and parties in the 90s was bigger than just an individual scene. When it came to the parties like the Shed 14 dock parties produced by the ALSO Foundation, it wasn’t about ego or politics. Everyone had to go.

‘Melbourne just had a different togetherness, the drag queens were doing some really great artistic stuff, and there were great lesbian nights. The whole art thing here was very proactive.

‘The thing I loved about Melbourne in the 1990s was that there was so much going on and so much fun stuff to do. There were so many creatives, and so much different work. It was a really buzzy art scene, much more than Sydney. Besides that, there were great clubs like Tasty all just starting out.’

The fallout

Out of the 463 patrons who were strip searched, only eight arrests were made, six for minor drug offences, one for being drunk in a public place, and another for abusive language. Still, in the days and weeks following, Chief Superintendent Peter Graham was spotted in the media more than once claiming the raid had been a raging success.

In contrast, a 1996 class action, led by about 250 patrons, resulted in a payout of $6 million. It would have been more but a number of patrons declined to participate, not wanting to reveal their sexuality publicly.

Filing for false imprisonment and assault, each claimant received over $10,000 in damages. Sixteen years apart, Tasty is as important, if not as public, a moment as Australia’s first Mardi Gras in Sydney in June 1978. Both landmark events challenged further the myth of our inner cities being safe harbours.

By the end of the 90s homosexuality had been decriminalised across Australia, with Tasmania the last state to “join the party” in 1997.

At this point, Cindy Pastel was getting ready to feature in an even bigger party – the closing ceremony of the 2000 Sydney Olympics. Appearing on top of a giant glittering stiletto heel, it was a testament to how far Pastel had come since losing that first talent show two decades before.

In spite of this progress, it wasn’t until 2014 that Victoria Police officially apologised for their actions on the night of the Tasty raid. After 20 years, and despite invitations, none of the arresting officers who were present on the night of the raid were present for the apology.

Two steps forward…

Despite relationships between the queers and the police having since warmed, we need only reflect as far back as 2019 to peer behind the PR. When history repeated itself, it was in the early hours of 11 May when Hares and Hyenas – a queer-owned bookstore, café, performance space and home – was mistakenly targeted and stormed in another botched raid by Victorian Police. The action resulted in an innocent man receiving serious injuries.

To say there were not only homophobic but also racist undertones to what happened requires no stretch of the imagination. Officers later admitted to mistakenly arresting Nik Dimopoulos ‘for looking Middle Eastern’. Dimopoulos who is not Middle Eastern is, however, a pillar of the queer community. Like those who had come before, Dimopoulos took legal action against Victoria Police, reportedly receiving a confidential settlement in August 2022, and a rare admission of fault from the Victoria Police Assistant Commissioner Luke Cornelius. It is to be hoped that his experience may lead to a better future for those who follow.

In Part II of Queer and Present Danger, we step into the new millennium. Leaving the inner city behind to meet at the intersection of drag and the 65,000 years of the world’s oldest living culture, we meet Crystal Love who speaks from her home in the Tiwi Islands.

With politics front of mind, Part II will end in our nation’s capital, as First Nations Queen Mad B Diva breaks down what it’s like to be a parent, queer person and drag queen during the era of the Safe School Program and the main event in 2017, when us queers were finally allowed a white picket fence all of our own.

Read: Queer and present danger: Part 2 and Queer and present danger: Part 3

This article is published under the Amplify Collective, an initiative supported by The Walkley Foundation and made possible through funding from the Meta Australian News Fund.