William Yang is a Queensland-born, Sydney-based photographer who has added his own personal narrative to Australian photography over the past five decades. As we celebrate Mardi Gras this week, it is timely to look at Yang’s reflective and joyous depictions of Australia’s LGBTQI scene from the late 70s and 80s through to the present.

His photography and theatre works have also been deeply informed by the cultural and political pressures of growing up as a gay man from a Chinese immigrant family in north Queensland, a dive into identity explored in his forthcoming exhibition.

ArtsHub caught up with William Yang to talk about the shifting role his art has played in those narratives, and the challenges of facing your life’s work in mounting a survey show.

ArtsHub: William, your work has a strong storytelling quality. Do you think COVID has impacted the way we tell stories and forced us to rethink relationships and empathy?

William Yang: I don’t know about that – didn’t strike a chord with me that way – but maybe it has made us be more introspective. I don’t know if people have really changed that much. I have been through AIDS, and it was a lot worse for a gay person than COVID – it was terrifying.

In terms of storytelling, I do refer to AIDS in this exhibition, so that is a good reminder of pandemics in our age of COVID.

AH: Tell us more about how you use storytelling as ‘a medium’?

WY: It had its own evolution. It started with me doing slide presentation and my tendency to talk with the slides. I did that for about seven years before I did my first performance piece – people like it as a format – so I kept doing it. Overseas entrepreneurs liked my performances so I started to tour them for about 15-years, but I was hardly ever asked to tour an exhibition. They used to call me ‘the storyteller’.

AH: Why do you think that was?

WY: Performance has got stories, images and music, so it is a more complete experience than a gallery. Plus, you pay your money to buy a ticket and that is a commitment and go, but for a gallery people half-heartedly walk around while they are thinking about lunch.

AH: Did you like that term – the storyteller?

WY: I loved it! There is a that tradition a bit in Australia

AH: What about Chinese culture, is there a similar narrative tradition? And how have these two things come together in your work?

WY: Not so much. I have done many workshops in China and they find a personal story a bit alien, because culturally they are more communally minded – their ideologies and socialisation is toward the communal rather than the personal.

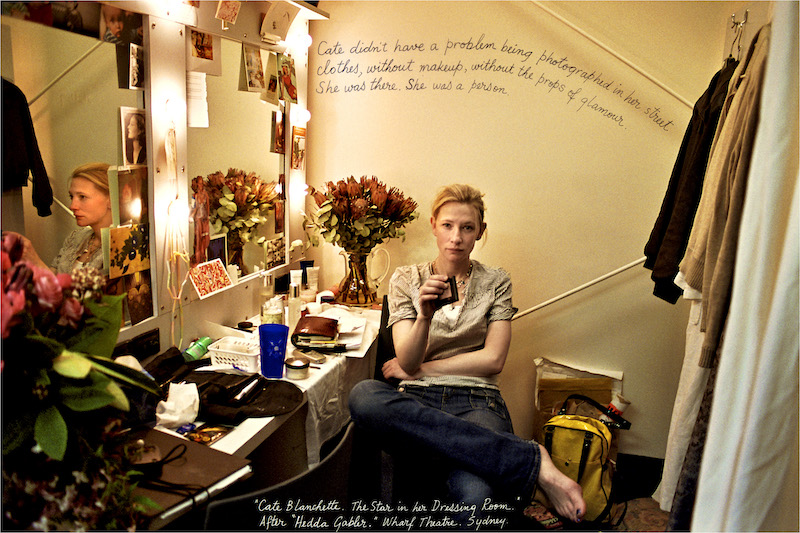

Cate Blanchett: The star in her dressing room. After Hedda Gabler. Wharf Theatre. Sydney. 2004 Image courtesy: The artist © William Yang.

AH: Tell us about the use of text in your artwork, which really plays out that storytelling aspect.

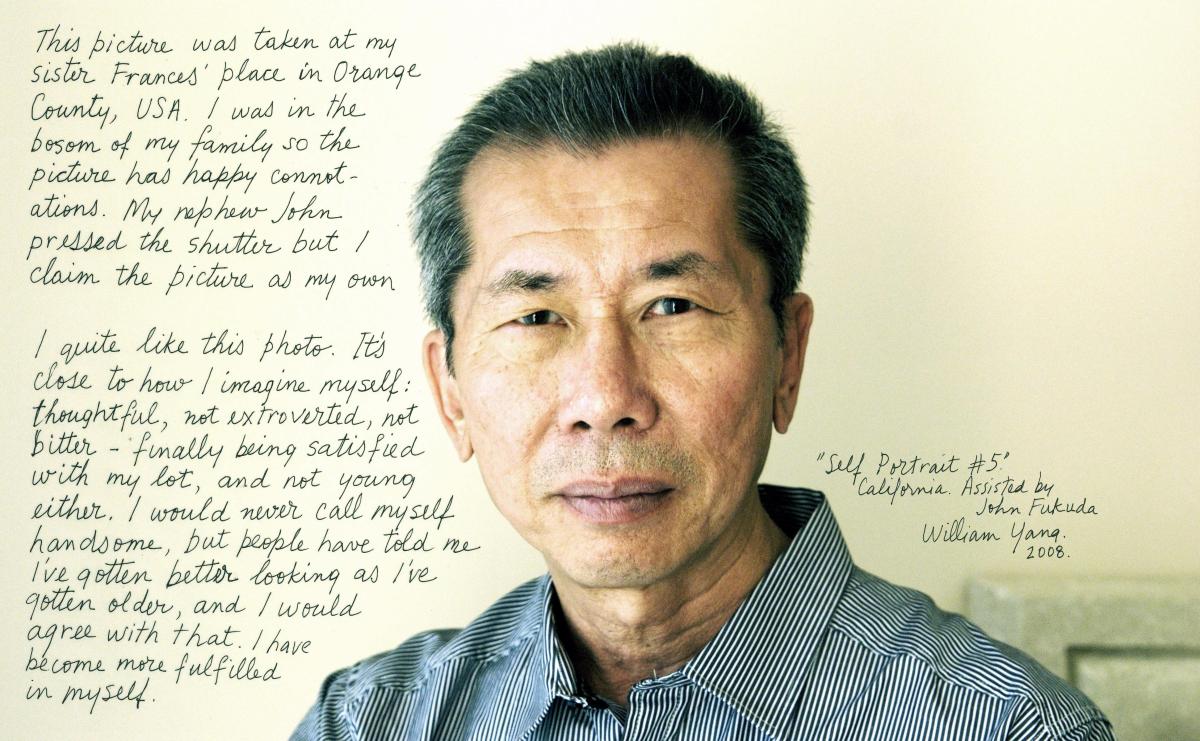

WY: My images have stories [behind them], so when I started presenting them in the gallery I just wrote on the print. The only different thing now is that I sometimes digitise the writing and scan it on to the print, but that can be more nerve wrecking.

AH: Your survey exhibition at Queensland Art Gallery is called Seeing and Being Seen. Tell us about being seen as a gay Chinese man, as Australia was grappling to emerge from is conservatism.

WY: Sex comes into my work a lot. I had to liberate myself as a gay man. We don’t have conversations about sex in our family. I suppose culturally, Chinese think you don’t need to talk about these things in public. But it is not exclusive to growing up Chinese. I have had gay Jewish people come up to me and say you don’t have to say you are gay.

These taboo subjects, they are all part of my story – and I suppose one of the things I am trying to say through my art and this exhibition is that suppression is bad for your health.

AH: A retrospective can be challenging – to confront yourself through what you have made over your career. How do you choose what to include and what to leave out?

WY: I had a curator help me and it was a very intensive, difficult process of whittling down thousands of works to just 260 that we have chosen – they freaked out with that number in an exhibition). [That selection] wasn’t theoretical in contemporary art sense. It was mainly finding the categories that we could make into sections.

We chose early stuff, my early childhood growing up Chinese in Australia, which then morphs into my Chinese identity and that became a big theme of my work for many years… The other big section is the gay section, which we kind of went with Mardi Gras as the popular flagship of the moment, perhaps at the expense of another section, which I would have liked to explore but not just another room.

AH: What was that section?

WY: Scenes of gay life – that section went. But there is a section I like a lot about the male body – male nudes from a gay perspective, which were taken from very early to recent times.

And there are two other sections – social photography, which is actually the stuff I am really well known for but mainly Sydney based. In this process, the whole exhibition had to skew towards Queensland. And the final part became quite a big section on landscape.

I like the word “retrospective” to describe the exhibition rather than call it a major survey, which is more technically correct. Retrospective or looking back on past events aptly describes the process I have been through. How satisfying to be given the chance to reflect of one’s life and work. How fulfilling to feel recognised as an artist in a marginalised art form, photography. Once you go through this process there is a certain resolution.

AH: Tell me more about that marginalisation.

WY: Painting has always been the traditionally accepted medium, and photography in Australia in the ’70s was both marginalised and regarded as a new art form – so it had some cache as the new medium – it has gained more credibility today, and there are major artists who choose it over painting.

AH: For you, it has always been a very easy slide across mediums – from performance to photography, to video. We take this for granted now, but practice was more siloed in the past. How did you struggle with this?

WY: Part of my success with performance was that it was newish then. We are talking more than thirty years ago. One of the things about this exhibition that I am most happy about, it that it includes a few of my video works, which helps to break up the show, but also they [blend] in that performative part of my work – and my voice is in them.

AH: Any closing thoughts?

WY: As in any storytelling, I am the protagonist in this story – the exhibition – and quite strongly so. I travel through the exhibition as self- portraits in time. I want people to laugh and to cry in my exhibition.

William Yang Seeing and Being Seen opens at the Queensland Art Gallery 27 March and continues through 22 August.