From queerness to emotive desires, Sydney-based artists Venn Miles, Kansas Smeaton and Chloe Kang explore disparate identities through oil painting.

Holding by Venn Miles

Venn Miles has always worked large-scale. He picked up his first set of oils on his 22nd birthday, as a trade-off for boredom when the pandemic rolled around in 2020. He blasted Amy Winehouse in his Belrose family home and got to work. There he created the first painting, Holding, which Miles finds inherently homoerotic. Queer themes thread ubiquitously in his work, as well as commentary on the glorification of substance abuse. The latter is a message he wishes to dispel: ‘It’s a wake-up call, but also a comforting, pleasant intervention.’

As a result of his upbringing, Miles has a morbid fascination with suburbia and, to greater effect, Desperate Housewives. His childhood in Belrose could almost pass for Wisteria Lane, with its panoply of tree-lined streets and manicured white women. Elements of sub-pop culture spring from his works. There are traces of his parents in everything he does: his father is an excellent drawer, and his mother – a total Oxford Street babe in her heyday.

On the topic of mass digitisation – the red-scare of our current generation – Miles says: ‘I definitely wouldn’t work against AI, but I also don’t know if art or the visual arts will be affected as much as branding or marketing. The humanity of art is its driving force. It’s what keeps everyone coming back.’ For him, it’s not an attitude of concession but a helpful tool.

Self-identifying as a contemporary painter comes with drawbacks, such as this idea of the Renaissance Man, and the linearity people draw between it and painting. Even today, one cannot shake the association of this Western ghoul, archaic and musty with rot. Miles agrees, and adds that he wants no bar of it. There’s a whole lot he finds exhaustive, and the footnotes that come with being a contemporary is another. Miles says: ‘A lot of artists still need to be making art for people who know f**k-all about art, and that’s heartbreaking.’

Miles believes that visual language is something people don’t mean to follow, but end up cohering to. In Untitled, this is palpable in his brushwork – all distorted figures and heavily striated lines, scratchy with practised imperfection.

In Miles’ pictorial universe, the distorted figures float on the canvas with blank expressions. This is a stylistic choice adopted early on in his career from his major Higher School Certificate (HSC) work. ‘I want them to appear pensive,’ says Miles. ‘They have a lot going on up there.’

The posing, however, is a tell-all. Miles’ surrealist spin on still-life portraiture speaks of balance: the melody of the indistinguishable moults into heavy line work and, yet, this subject remains an apparition. We may not know who they are and, perhaps, neither do they.

Spike with Grapes by Kansas Smeaton

Kansas Smeaton’s paintings are bespoke and immediately recognisable. Her work is replete with bows, hands, fruits and fabric. Ribbons are fondly relegated as an exclusive “for the girls”, and even fabric is seductive. When she paints the curves and folds, viewers find the silhouette of a body.

Smeaton is concerned with the imprint of desire and frivolity in her work. Her subjects are almost always femme and, if they are not, they are arranged as such. One of her favourites pieces features her partner Spike, bare-chested, pawing at a cluster of grapes. The painting ends at the base of his pelvis where the canvas meets the imagined line of sight – leaving viewers to fill in the blanks.

Smeaton is a revisionist in that way. The impressions from the Rococo era of 18th century France reside in her work with a modern day remix on portraiture – featuring an outcrop of people who in those days would have been hung and quartered. Among them are sex workers, queer couples and intimate friends of Smeaton in varying stages of undress. Every work she makes is a self-portrait; in her bequeathing of them on canvas, Smeaton sees herself.

On her abiding fascination with that particular time period, Smeaton says: ‘They’re just how regular people are and what things were like. Someday someone will say that about us too.’

In a way, things were more liberated back then. Sex work was provisional and treated as such, and whole swathes behind the city walls were assigned for red light district work – conveniently endorsed by the church. ‘Even then, they knew what happened when people couldn’t express themselves,’ continues Smeaton.

Friedrich Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy plays a pivotal role in her work. Apollo of the arrow-headed order is drawn in conjunction with Dionysus, the deity of revelry and destruction. The world is heading in Apollo’s direction – there’s not enough hedonistic compulsion. As Nietzsche suggests, the imbalance would be fatal.

With this in mind, Smeaton conjures these earthly delights tenfold in her work. There’s lewdness in artful smudges: a whiff of impropriety in the exposed breast of a subject, or a flash of calf in pastel-ribboned stockings. The gradient background, be it the pastoral outdoors or silk-screened walls, points towards an exultant eroticism. What you see is an intuitive taboo. Here, darkness and light even out the creamy wash of the figures in the forefront. Only a Baroque and Rococo aesthete such as herself could be responsible for elevating such depictions of frou-frou allure.

One of Smeaton’s most memorable first encounters with art is when she played a fairy to Queen of the Fairies, Titania, in a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. From there, she blipped from New Zealand to Sydney and later Europe (where she exported that fantasy of daydreaming her girlhood away), before returning to Sydney where she lives and paints now.

We come to the conclusion that unmitigated purity would be ruinous. Smeaton lives half her life as wild girl and, from her perspective, the greatest scandal of grace in creating is that there really shouldn’t be one.

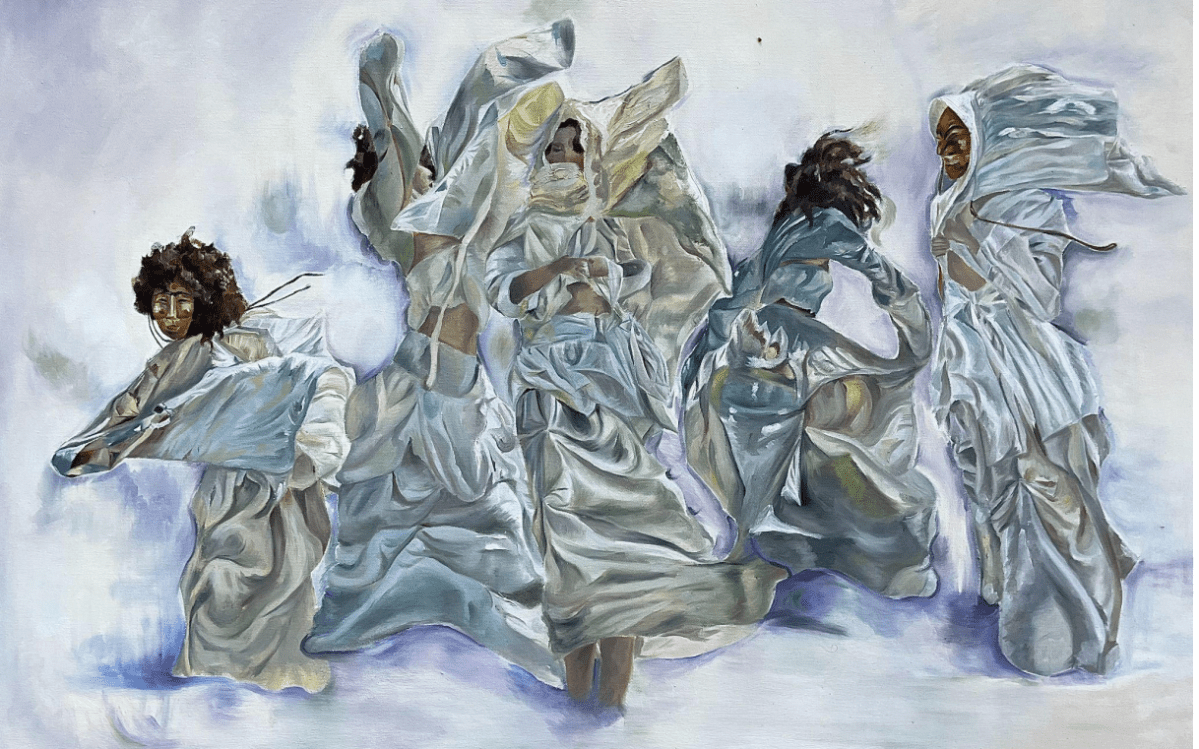

탈(Tal) by Chloe Kang

탈(Tal) is a reimagining of Korean identity by You Jong Kang (also known as Chloe). The painting features a Korean Australian woman dancing in traditional wear, as the movement of their hanbok weaves dream-like scenes in silvery, fluctuant course. The painting is hanging over Kang’s mantle. She says: ‘Look at the colours. It only makes sense when it’s on a piece of canvas, not in my head.’

Kang draws on the friction between motion and colour in her oeuvre. We see this in Tal with the rustle of the fabric almost becoming foliage, swept up in the rippling subject that glides over each corner of the canvas. Her practice is grounded in realism, yet the addition of green and purple (diametrical shades on the colour wheel) hints at a subtle departure from convention. Personality lurks behind the figures in cloudy shapes – a sprinkling of dark spots hidden to the initial glance becomes pointillistic and glaring when the viewer steps closer.

While the mask is a Western cipher for deception, guise and pretence, a Tal (Korean mask) signifies a world of difference. Its Hahoe roots hark back to the shamanistic period of South Korea as a wieldy storytelling tool, meant to inspire fortune and prosperity for its wearers. In Kang’s painting, the Tal was not an initial component of the sketchwork, but later superimposed onto the painting for additional effect.

When it comes to the partiality of vision from a perspective that is new and embodied, US scholar Donna J Haraway says one cannot “see” either a cell or molecule – or a woman, colonised person, labourer and so on – if one intends to see from these positions critically. Being is much more intricate and contingent.

In Kang’s studio, she is surreptitiously beholden to the fact that her work turns outwards for the masses to pluck at. Our skin is not our own thing, and neither is our art. It writhes under the contusions of what the world wants to add, and a lot of Kang’s first cues in painting come from what she initially felt held back by.

Kang says one time in a life painting class, she struggled to get the breasts right on canvas. She was disheartened until her teacher offered some words of counsel: ‘Humans will draw a feature they’re used to on their own face. If you ask someone to draw a breast, they tend to draw their own breast or their mother’s breast. You need to see what’s in front of you, and not what your mind sees.’

This was how she learned, but it also prompts the question: are we ever immediately present to ourselves in our art? Or is our perceptivity a disproportionate reframing of what our body of work actually is?

Kang’s trip to South Korea earlier this year was a breakthrough moment. One night she walked alone on a wide intersection in central Seoul, where in a magnanimous, fleeting second she was struck – she felt small, in a very significant way. Kang says: ‘It was warm knowing how passable and fleeting everything is. Everything fizzles.’

Tal is an account of joyful mortality and, in a larger vein, all the forementioned pieces point to the idea that we are instruments and identities of boundless capacity. Bound to no temporal beat, the work of these three artists demonstrate the permeability of their worlds – one viewers are invited to visit.

So let us move.

This article is published under the Amplify Collective, an initiative supported by The Walkley Foundation and made possible through funding from the Meta Australian News Fund.